Suzy Hodgson at UVM Extension’s Center for Sustainable Agriculture (CSA) interviews Amanda Andrews of Tamarack Hollow Farm about her experience with farming on a floodplain in Vermont and her recent move to higher ground.

Can you describe your move to Vermont and farming on the floodplain in Burlington?

Amanda: I moved up here in 2010 after working on farms in New York State. My partner and I started leasing land on a former dairy farm, which had been abandoned in 1978. It had changed hands a number of times and the City of Burlington wouldn’t allow residential development; it was zoned agriculture, with the Winooski winding between it and the adjacent Ethan Allen Homestead and the Intervale Center.

We knew the Intervale Center socially and knew about the Winooski prime soils there. We knew it was floodplain and what was happening at the Intervale, where it floods yearly in the spring with the snowmelt. Our farming friends said that we’ve only had one flood that was ever a problem in the 20 years we’ve been here. It’s a “non issue.” Flooding wasn’t holding anyone back.

Tamarack Hollow Farm. Photo credit: Amanda Andrews

CSA: What was your experience farming on the floodplain?

Amanda: When we started our farm, there was no problem. We had a normal planting season on 2.5 acres and as part of our lease agreement, we rejuvenated and cleared 35 acres for new pasture for our livestock in 2010. But in 2011, there was the heaviest snowfall in 30 years and that spring was the heaviest rainfall. That year Lake Champlain flooded where the Winooski meets the Lake and it backed onto our farm. The lake level reached a record high of 104 feet. This was our 2nd spring so we thought it must be a freak occurrence. We were under lake level and the water didn’t clear off until the end of June when we could plant.

CSA: When and how did you make the decision to move to higher ground?

Amanda: At the end of August 2011, Tropical Storm Irene hit and our farm was flooded again. 2011 was a total loss.

Having two major once-in-a-lifetime events in one year, we decided seriously to think of moving even though we had just arrived.

Summer 2012 was really great but still in the back of our minds, we continued looking, talking with the but most of the available land was large dairy farms without much vegetable soils, and we didn’t want a mortgage, a big old barn, and be tied to livestock. The economic collapse of 2008/09 meant people weren’t spending $12/lb. on meat.

Summer 2012 was really great but still in the back of our minds, we continued looking, talking with the Vermont Land Trust but most of the available land was large dairy farms without much vegetable soils, and we didn’t want a mortgage, a big old barn, and be tied to livestock. The economic collapse of 2008/09 meant people weren’t spending $12/lb. on meat.

In 2013, our farm flooded in May, June, and July. Spring snowmelt wasn’t a problem; it was heavy rains. We had standing water on our farm and an adjacent wetland took over 10 acres of our vegetable fields. On July 4, a microburst storm came over the lake from the Adirondacks and hit Burlington; sewers were overflowing in Burlington. The next day the river flooded and our farm was flooded.

Standing water on spring greens, Tamarack Hollow Farm, Burlington, May 26, 2013. Photo credit: Amanda Andrews

CSA: What were your losses?

Amanda: We had done all our direct seeding in April. We’d planted peas, carrots, beets, potatoes, tomatoes, winter squash, spring greens, we lost all spring and summer vegetable. We had to move all our livestock, equipment, everything off the farm.

We put all our workers in furlough and lost upwards of $75,000 worth of produce. We waited for the farm to dry out, and at the end of July, we planted everything. What did work to our advantage is that since we lost so much in May and June, we seeded extra fall crops as we had extra space. Having lost the spring crops, we had space for fall crops, broccoli, kale and kohlrabi. We seeded heavily and had an OK fall – it didn’t put us out of business. If we had flooded again that fall, it would have been the end.

CSA: Have the weather-related effects of climate change been what you expected? Have they been manageable?

Amanda: What we experienced in Burlington, it wasn’t necessarily the snowmelt, the historic reasons for flooding, it was heavy rainfalls, short duration, and very very heavy. With four inches-in-a-day rain storm, even if you’re not on a floodplain, that sort of rain can still screw you over. I’d make crop plans over the winter with contingencies on top of contingencies. If there is flooding in May, this is what we do; if there is flooding in June, this is what we do. If in August… I had to have contingencies for all of these as we were going to flood at some point during the growing season.

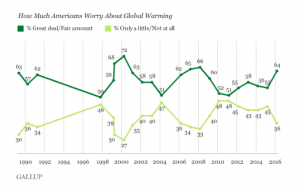

People said it’s a flood plain, what did you expect? Floodplains flood predictably, but what happened in the past five years is totally unpredictable flooding and that’s the difference. It’s not that you’re going to flood between April 1 and May 1, which is what it had been for hundreds of years.

Now, you might flood in June, July, and/or August; we have experienced flooding in every summer month. That is not in the historical record. The Winooski flood plain is farmed in every town the Winooski goes through. Because we were closest to the Lake, we got it the worst. We got everyone’s floodwater but we’re not the only ones going through this.

It’s definitely a risk, if you’re further upstream, flooding may be manageable. Downstream, we were flooding that much more often. It’s a tradeoff for that prime soil.

CSA: What particular site characteristics were you looking for beyond higher ground?

Amanda: A lot of the farmland that exists in Vermont is on the Winooski and for obvious reasons we shied away from this. What we wanted was really, really well-drained soils. We weren’t interested in dairy farms as they had poorly drained and shallow soils. And anything with clay was out. I cross-referenced potential agricultural parcels with the State’s soil maps for soil types, topography, forests, wetlands, and water bodies. We found an agricultural parcel with Vershire-Dummerston complex – a sandy loam – which is very well drained., not A+ but 84 on the scale 1 to 100 with no asterisk for flooding risk like our Winooski farm.

Plowing the new farm, Tamarack Hollow Farm, Plainfield, May 9, 2014. Photo credit: Amanda Andrews.

CSA: Are you planning to change your crops?

Amanda: There will be slight change in our crops. Down at the Intervale, our planting was bottom heavy. Our experience of climate change is that the spring season is shrinking; it’s later to start, with very heavy storms, and heats up rapidly. Now we have high dry land, so we can get to our fields in spring but spring is not as long.

My experience is that spring is starting later and ending earlier. We’ll have high tunnels for spring production and perennials that come up on their own so I don’t need to be in the fields to cultivate. We’re trying to do things that aren’t dependent on tractors in the spring when soils are wet.

A big risk is increased diseases. We’re getting diseases and pests that used to just affect southern growers. We don’t grow berries yet and are looking carefully where we put them. We are looking for disease resistance in our seed varieties and there’re lots of successful breeding programs and surveys to see what farmers need in varieties.

It is troublesome. I wish we could grow all heirloom varieties, but as diseases are shifting, the resistance packages bred into the heirlooms no longer cut it. And we have new weed species moving up from the south. We need to know how much viable weed seed is in the soil and to keep that down as a long-term management goal.

CSA: Moving forward, how are you planning for climate and weather changes? Any specific example for plants?

Amanda: We’re buying rhubarb and asparagus and getting perennials established. We’re growing more herbs as you can get them in the ground earlier in the spring. The first project we did after water and power was put in a huge walk-in cooler. For us, business plan-wise, lots of fall crops are easier to grow, fall is extending.

While we’re losing spring, we’re getting longer falls. So we are trying to be very fall heavy to make more income in the winter so we can be buffeted from the shorter spring. It’s a shifting calendar.

We’re not considering strawberries, it’s becoming more and more difficult due to a lot of spring rain making it difficult for strawberries to fruit. Ten years ago, we probably would have put in an acre of strawberries as that was the thing to bring people to your farmstand. Instead we have ton of storage crops that we can sell in the December and January and markets have been responsive. Now you can grow rutabagas and carrots and sell them.

CSA: What advice would you give to other farmers from what you learned about climate change?

Amanda: Farming was hard enough before climate change, it’s not like it was easy before and now it’s really hard. If you really want to be a farmer, there’s nothing that can be said to keep you from trying farming. What did the farmer do when he won the lottery? He kept farming until it was all gone. You’re going to keep doing it until you’re broke.

I can’t imagine surviving climate change in a bubble. Our greatest resource for planning and surviving is communicating with seed companies, growers, Extension services, knowing what’s happening in southern VT, MA. What’s a problem for them this year will be a problem for us next year. I have peers in Pennsylvania and talk to them all the time.

If you look at Vermont projections for climate change in 50 years, it’ll be Pennsylvania.