Since the last time I visited my phenology site, much more new growth has emerged. Many of the fiddleheads had opened up more or were fully open, and the ferns were much taller than last month. There were blooming flowers, particularly trilliums and small field flowers, scattered across the ground. There was also a lot of understory growth, with tiny 1-2 year old sugar maples only a few inches tall beginning to leaf out. The rest of the more well-developed understory had filled out much more, with more leaves unfurling on the branches. Similarly, the forest sounded much more active; I constantly heard an array of bird calls (particularly woodpeckers and chicadees), rustling, and chipmunks.

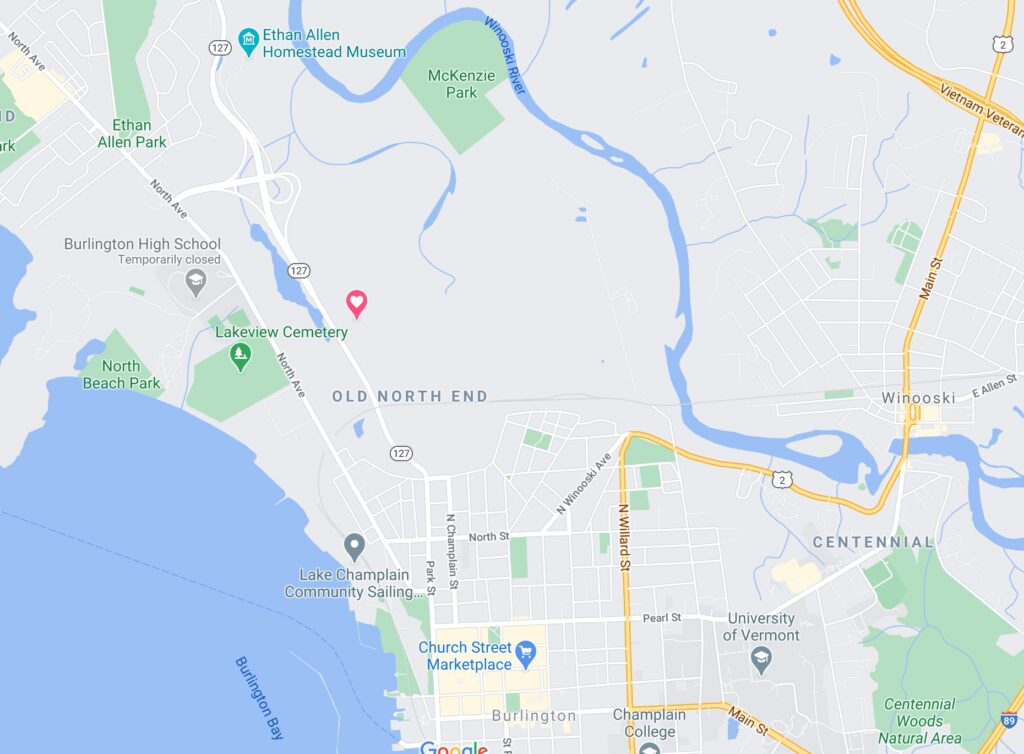

I think that the biggest way in which nature and culture intertwine at my spot has to do with recreation in the area. Although my area is off the trail, I’ve seen quite a number of individuals hammock or hikers wander down into the valley when I’ve been down there, implying that human interactions are still occurring at the site. Although there may be less damage to the ecosystem than right off the trail, there is still trampled plants and disturbed ground. As with the rest of Centennial, the woods offer locals and students the ability to experience the outdoors within the city. Personally, stepping into my site has offered me a sense of peace and tranquility, despite the sound of the planes overhead or sirens in the distance. I think that Vermonters value the woods, whether its for running, hiking, reading, school, or just wandering around. As Centennial is easily accessible, the area offers a chance for humans to disappear into the outdoors for a bit.

I don’t necessarily feel as if I’m a part of my place, but I do feel a connection to it. Because I do not largely impact the ecosystem, I don’t necessarily think I have a large role in the place as a whole. However, I do recognize I fit into the system, as my presence impacts the life around me. I think that the biggest way that I “fit into” my site, however, is through a self-decided connection to the area just from watching it and routinely visiting it throughout the semester. Although I don’t see the site as “mine” and I recognize other people visit it, I do feel as if I have gotten to know the place well and associate a sort of importance to the area. I noticed this most on my last visit, as I realized I was a little bit sad about it being my last official “phenology visit”. I also noticed how I felt almost proud to see all of the new growth, and a connection to all of the small saplings sprouting or flowers opening up. It was nice to see a place that I had created a connection with thrive and healthily enter into spring after such a long winter.