On a brisk afternoon in early May I biked to the quarry to make some final observations before the end of the semester. The chives that had begun sprouting at my last visit were out en mass, as was the stonecrop which seemed seems to thrive on the rocky surface. A few dandelions poked their flowers above the chives, but this unique environment seems to rob them of the adaptations that make them prolific invasives, and they were outnumbered by the purple flowers of ground ivy.

Bountiful chives Stonecrop

A few dandelions Lots of ground ivy

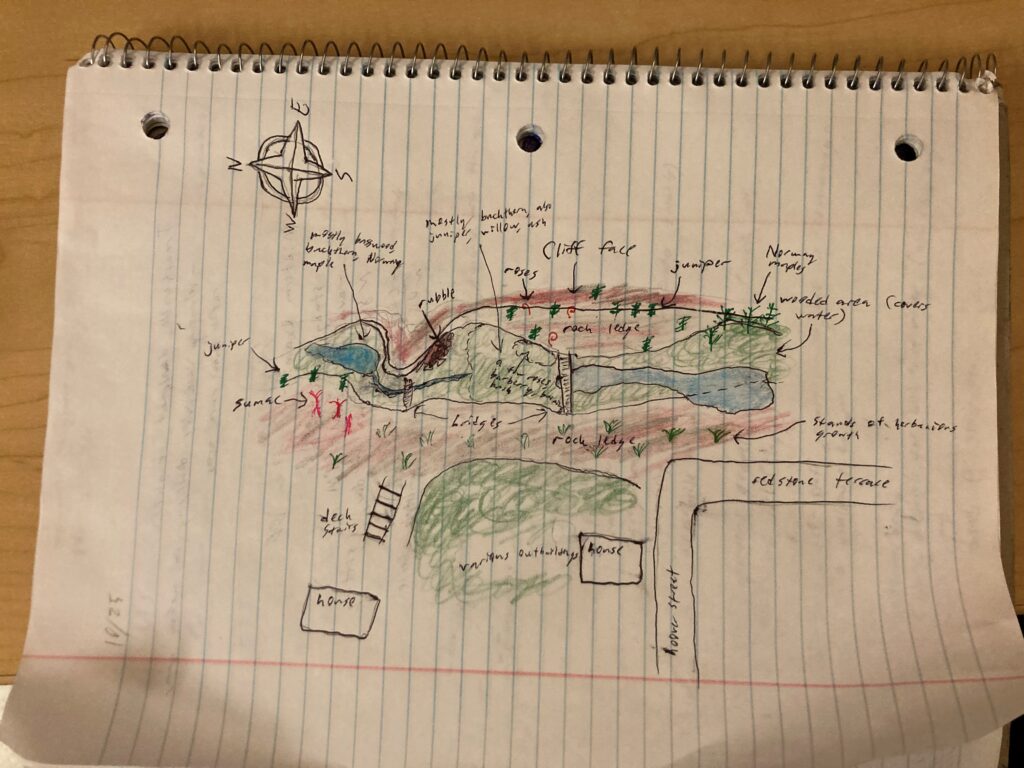

One small tree (possibly a hickory) was still in the process of leafing out, but the forested area and parts of the cliff were dense with the leaves of honeysuckle, maple, buckthorn, and cotoneaster. The juniper and cedar retained their leaves as well, but were looking somewhat brown and faded; for evergreens, springtime doesn’t seem to be the time of growth and renewal that we know it as.

Unknown tree leafing out Cotoneaster

Evergreens after a long winter Newly leafed deciduous trees

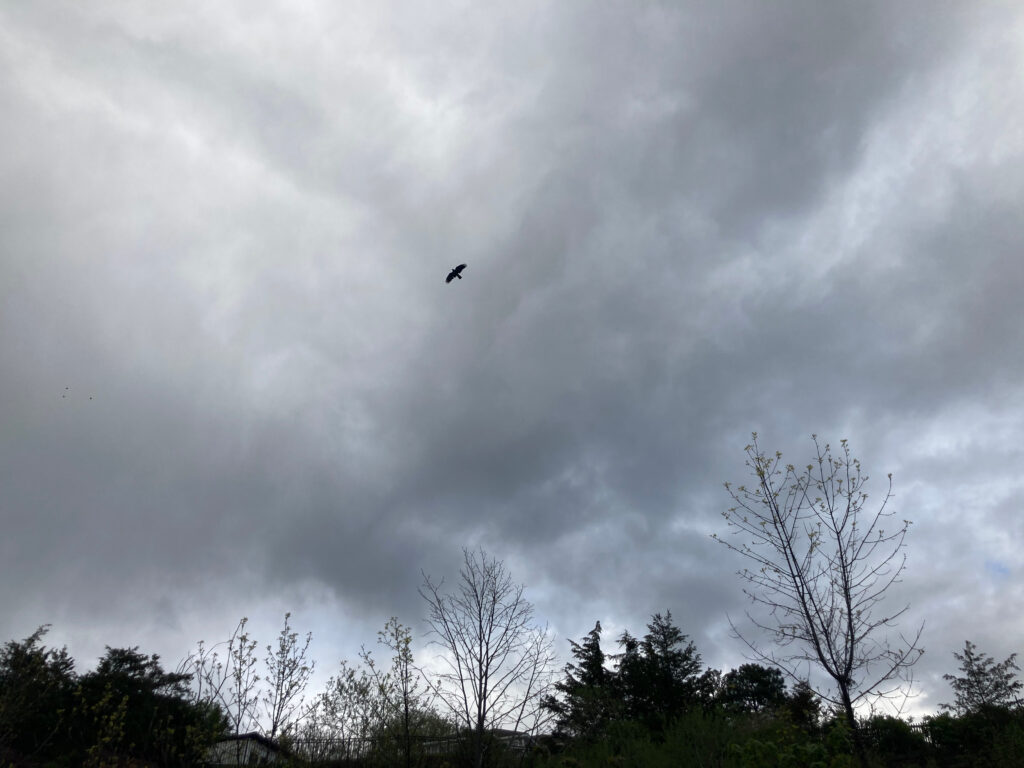

Climbing the cliff, I found that the strange trickles of water remained, and a few hardy honeysuckle plants had made homes among them. From above, a patch of succulents on a ledge looked like a garden tended by elves or gnomes. Descending the cliff I made note of a crow flying above and a woody plant with pink flowers.

Hardy honeysuckle Elf garden

A crow in flight A beautiful but unidentified flowering plant

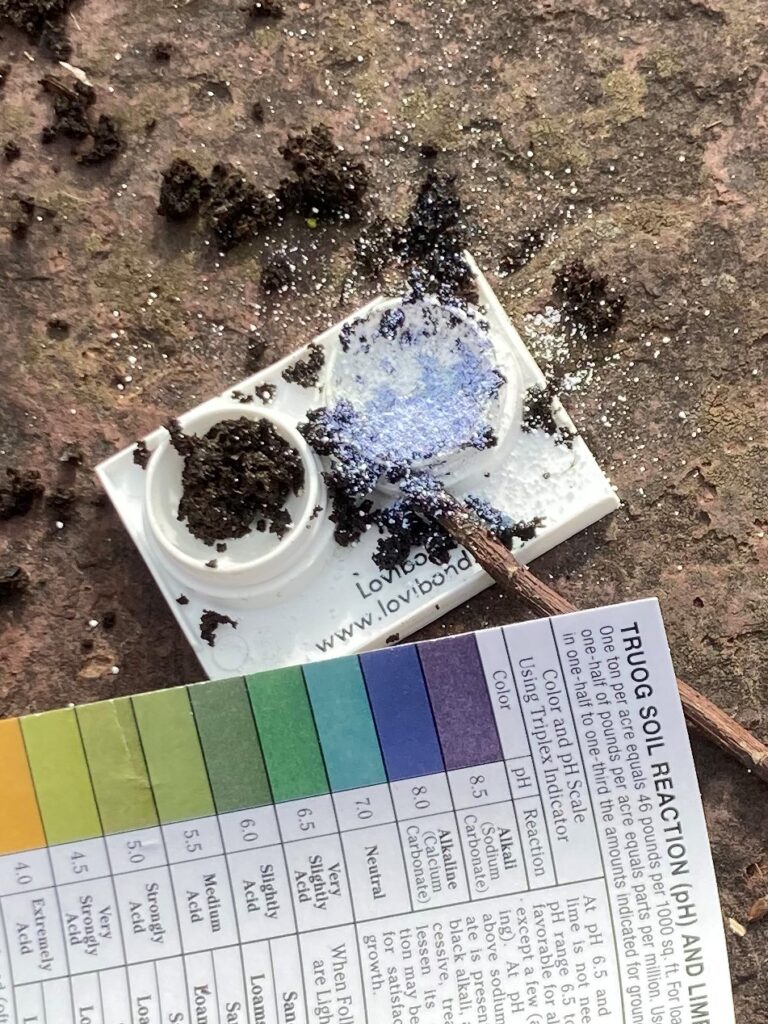

The evolving relationships between people and the land are evident at Redstone Quarry. I was unable to find information about whether it had any particular role in Abenaki culture, but since the 1800s it has played a significant role in the lives of those who live nearby. As one of the largest working quarries in the area, beginning in 1805, it provided materials for many buildings that still stand in Burlington and at the University of Vermont. Evidence of quarrying activity is visible in its exposed rock and steep cliff face. College classes have taken advantage of its unique geology at least since the late 19th century, and now its status as a natural area provides opportunities for residents of Hoover Street, nearby neighborhoods, and the greater Burlington community to interact with nature. It is rare that I don’t see at least one person or family strolling through during my visits. A little free library has been installed in front of the house bordering the quarry’s enterance, an act of reciprocity towards the community that inspires optimism for the future of sustainability and community-oriented living.

A panorama from the top of the cliff

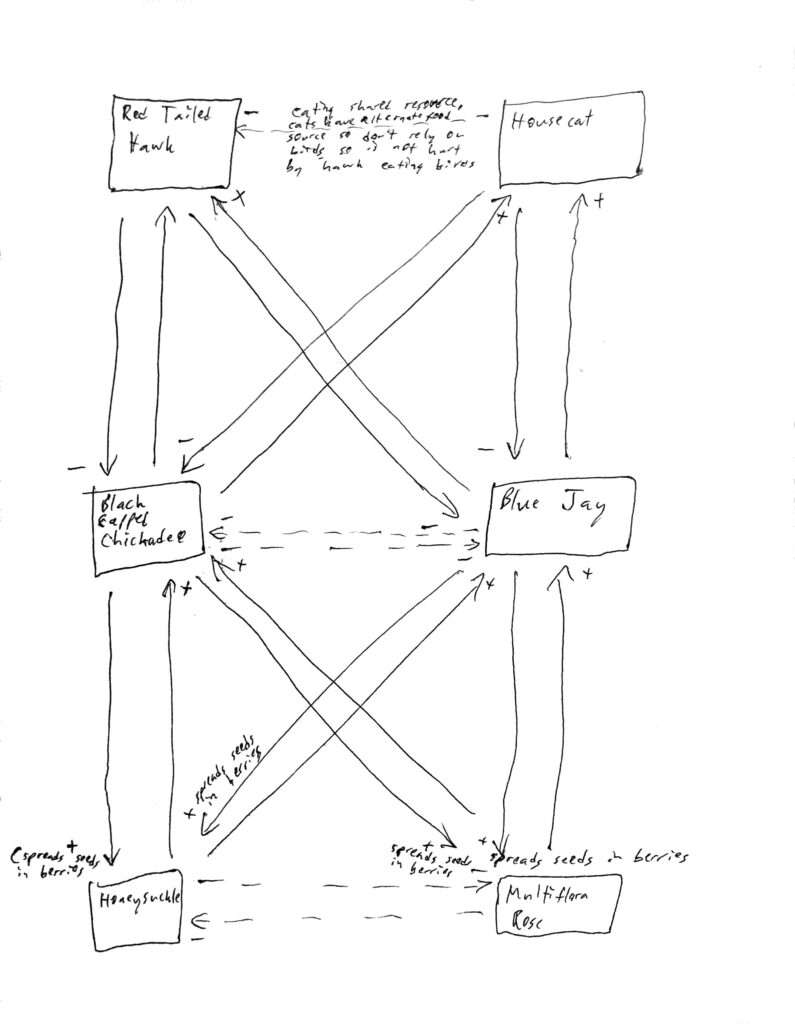

The question of whether I consider myself part of the quarry is more difficult to answer. My presence doesn’t have a significant impact on the quarry’s natural systems. I do not participate in the maintenance of the walking paths, and I am not part of the food chains documented in the species interaction diagram I made a few weeks ago. My role in the quarry is that of an observer rather than a participant. However, it is unlikely that my photo and note taking captures exactly what existed before I arrived in an objective manner, so in that way I am creating a new version of the quarry for anyone who reads my blog, and in that sense I believe I am part of the quarry in an outward-facing sense. I have encouraged many friends to visit it, and I enjoy sharing what I have learned about the site. It is one of my favorite places in Burlington, so I also consider the site part of myself. As I prepare to go home, I leave the quarry much as I found it in September: green and full of life.

Until next time