I took my last walk of the semester over to Centennial Woods on a sunny day in the 60s earlier this week. It was the warmest and sunniest day that I had seen my phenology spot since the fall, and it was so wonderful to see the little heads of new life poking up from the dirt again, as well as listen to the once-again babbling brook.

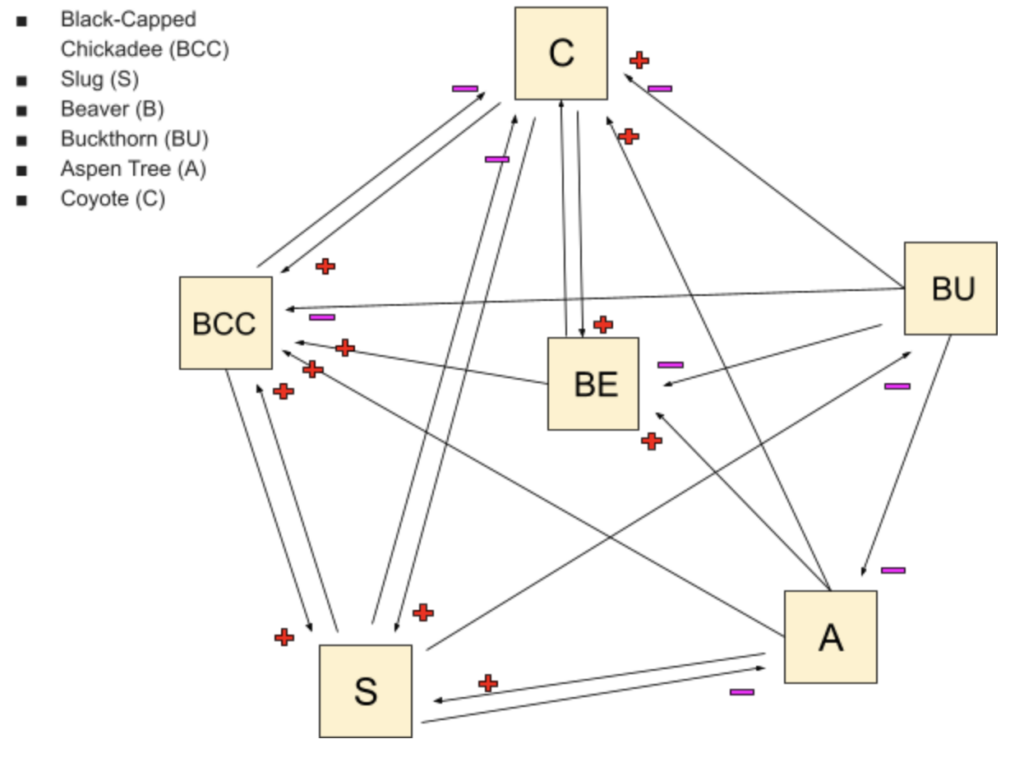

My Species Interaction Diagram highlights six documented species in Centennial Woods: Black-Capped Chickadee, Coyote, Land Slug, Aspen Tree, Buckthorn, and North American Beaver.

My species interaction diagram highlights the interactions of four animal organisms with two species of tree, one native and one invasive. Aspen is one of the most popular trees for beavers to gnaw on and use to build their dams, as well as offers coverage for Black-Capped Chickadees and the prey of Coyotes. Common Buckthorn is a wildly invasive species in Centennial Woods and the greater Burlington area, and its population impacts the abundance of the native aspen tree that other species rely on. Between animal organisms, beaver habitat actually helps bird populations due to the vegetation growth the dammed brook brings. Coyotes are the top predator of the natural community interaction. They are omnivores so they will basically eat anything in the diagram, including beavers and insects.

Centennial Woods is a natural, but open to the public, area. The big question that comes to mind when discussing the usage of such areas is, how can we foster an area that humans may use for recreational, educational, and psychiatric benefit without compromising the health of the natural community? Whenever there is a natural area that is being shared by humans, nature and culture instantly become intertwined. The health of both groups become interdependent with one another. Management of Centennial Woods must be done through a socio-economic approach, with an understanding that access to the natural area for cultural benefit may put the nature aspect of the place at risk. Preservation of the nature of the woods will maintain cultural benefit of the area, while overexploiting cultural benefits of the natural area will face the risk of fostering an unsustainable and harmful ecosystem.

I don’t know if I would consider myself to be part of my place. I can say with certainty that I receive benefits from the natural area, as well as recognize it’s intrinsic value. I became very familiar and developed feelings of compassion and gratitude towards my recurring phenology spot, and there were moments when I would sit by the bank of the brook in my Hemlock Grove and feel as though I was melding into the mosaic of the landscape. However, I feel as though claiming that I am part of my place feels self-centered, when I am, in fact, a temporary visitor to the natural habitat. A place shouldn’t be defined on what humans receive from it, and I don’t think that any natural place should be categorized by the humans in and around it. This way, it’s easier to appreciate the intrinsic value of nature without getting caught up in appreciating nature only for the benefits of ecosystem services.

Centennial Woods is one of my favorite parts of campus. I was so lucky my first year to have been less than a ten minutes walk away from it from my dorm, and I feel as though I was really able to take advantage of the psychiatric benefits the natural area provided.

Thank you so much for a great semester! I’m leaving this course carrying so much information for my future studies with me!

Signing off,

Dani 😀