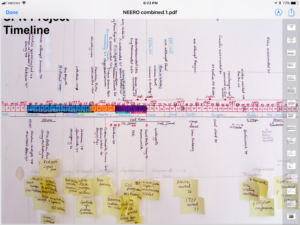

Personal Timeline

More specifically, it has been found that disclosure of one’s experience is most likely when the other person is perceived as a trustworthy person of good will and/or one who is wiling to disclose his experience to the same depth and breadth (Jourard, 65).

This book originated in my wish, once again, to make the world a better place. “The world,” in this case, is the world shared by young human beings learning to become effective and fulfilled elementary school teachers and the teachers who teach them. In the past several years, I have become increasingly aware that my position as an older white male of privilege carries with it a whole set of assumptions about the way I see myself as well as the way my students and other professors see me. Most particularly, I want to be seen as real, as relevant, and as useful to my students. And, I want to teach classes that are real, classes where language concerning issues of race, class, gender, and privilege are on the table for discussion, debate, and for learning. My awareness of myself, and my ability to relate that awareness to others as part of my teaching is a central ingredient in what makes my classes “real.” If I am unable to model and enter our discussions of learning, identity, method, learner, and outcome from a place that acknowledges the effects of personal and political positioning on what I do with my students, then I risk being a teacher with whom students “do school.” They’ll come to class, do the work, endeavor to give me what they’ve figured out I want from them, and then escape having never engaged themselves as important players in the drama that is the very human world of public education. They will leave believing classroom behavior, discourse, interaction, and hopefully transformation is the job of the student rather than the result of what happens in the space between teacher and student. If I want my students to be real with their students, then I must be real with them. If I want to be real with them, then I must endeavor to understand how I am seen, how others see me, and how our perceptions and misperceptions determine in part, what transpires between us.

Joe Ingham and Harry Luft[i] have an elegant way of describing the “big picture” view of my process here. It’s called the Johari Window. Their model of awareness in interpersonal relationships has been useful to me at various points throughout my several teaching lives. Joe and Harry would say that I am endeavoring to decrease my area of personal blindness with regard to how I see myself and how others see me (Q2). I am trying to increase what is known to me and known to others by learning more about how others see me (Q1).

|

The Jo-Hari Window |

||

| Known to Self | Not Known to Self | |

| Known to Others | Q1 – Area of Free Activity | Q2 – Blind Area |

| Not Known to Others | Q3 – Avoided or Hidden Area | Q4 – Area of Unknown Activity |

In my case, the “others” that I am interested in are the so-called “others” that my white students and I will meet up with in increasing numbers in America’s classrooms, including the classrooms of my own “predominantly white” university. Indeed, though we are exerting mighty efforts as of late to diversity our students, faculty, and staff, our label might more appropriately be “strikingly white” university[ii]. This suggests another motivation for wanting to write this book.

America’s public school classrooms are increasingly inhabited by students whose ethnic background is different and more complicated than mine. Truth be known, us people of non-color can have some pretty complicated ethnic mixes ourselves, except the rule of privilege governs our perceptions of the world much more than our ethnic inheritance. We are not dominated because of our skin color. Our skin color signals privilege; that it is we who are perceived to be the dominators. Their skin color does not signal such privilege. Lots of kids who look different from us are going to be taught by lots of people who look a lot like us. I take it as a given that our degree of success in those classrooms will in large measure be determined by how mindful we are of how the forces of power, privilege, and pigmentation, forces that run just beneath the surface of any classroom interaction, affect the way we are seen and the way we see others. Again, I take it as a given that successful teaching is grounded in relatively open, transparent, and supportive relationships. I don’t think these kinds of relationships are possible when faculty remain blind to how we are seen by “the other.” For teachers, our students are the “significant others” in our professional lives. We can’t just ask. The rules of privilege and power reduce the changes we’d ever get an honest answer. We must lead in revealing self in order to gain the same kind of respect from our students. Put more positively, gaining as much transparency as possible in the dynamics of teaching and learning will help create conditions of trust and support in the in the teaching learning relationship for all students. Transparency in the teacher creates a safer classroom for every student who walks in our classroom door, students of color and students of non-color alike!

Had I not modeled my own continual processing of identity formation, I don’t think Matt would have told his story, a story that was important for him to tell and his classmates to hear. Matt comes from Northern Vermont. His experience as a person of non-color with people of color growing up was minimal. On a trip to South, taken with his family during his high school years, Matt encountered prejudice. His family was passed over several times by the hostess in an all black restaurant somewhere in the American south. Matt and his family were hot and hungry. It had been a humid, southern summer’s day. They’d been driving for hours and had finally found a place to eat that they thought had good food and fit within their travel budget. Passed over many times as the only white folks in that restaurant, they were forced to wait and wait and wait until they were finally seated. Matt and his family concluded they were victims of racial prejudice. Now I don’t know how long Matt kept those feelings inside but I think it was at least three years between the incident and when he finally spoke about it in my class. That’s a long time to keep the feelings of embarrassment, degradation, and ultimately anger bottled up. Feeling free enough to talk about it in class meant he had a place and a context within which that sharing was appropriate.

I believe Matt talked about the incident of prejudice because I had begun to talk about my own bias and prejudice that were formed as part of my growing up and what the feelings and thoughts and perceptions of others were that resulted from those experiences. I shared some of my own experiences and the meaning those experiences had for me as part of a presentation on what it meant to grow up white. Upon the suggestion of a student in class, we opened a place on the course website for others to place similar stories in their own lives, stories like Matt’s and mine that framed some of the ways we looked at other people and some of the ways other people looked at us, especially around the dynamics of pigmentation, power, and privilege. Enough students shared to make the point that we all are caught in the complicated issues that race creates for us in our country.

Listening or reading through these stories, actually or virtually, was enlightening about who we were, what we thought about, how we’d made meaning from for some of us, quite uncomfortable events.. Academically, we could see where our experience meshed with what writers and researchers said about the effect of racial perceptions on identity formation. Personally, I think people felt better, safer even for having established a precedent where it was okay to talk and listen and hear things that were unspoken and kept hidden (Q3 on Joe and Harry’s matrix). Matt felt better about being able to share because he had a real context for the conversation that evolved. His story was part of the much larger American drama continuing to be worked out in this country. We were learning about identity formation at the time. I’d decided before the semester began that various typologies of group identity formation would be part of our syllabus. Matt’s sharing, my sharing, and the sharing of other students who put their stories on the web or who spoke up in class evidenced a need and desire to validate who we were and what we felt about the often unspoken and yet very powerful shaping influences of power, privilege, and pigmentation in our predominantly white lives.

I’m hoping my narratives might be valuable for other dominant culture teachers to read, especially if they encourage or inspire a similar kind of sharing. It isn’t comfortable all the time to offer up your own very personal and as yet unformed self concept for others to consider. But that’s what we need to do to even begin to have the conversations we will need to have if we are to be effective teachers in our increasingly multicultural classrooms.

We need to see ourselves as part of the multicultural matrix of possibility that America is becoming. Adults are thought to be fully evolved. At least that fantasy was set in my mind by some concrete operational Piagetian logic put in place long ago. Who’d have thought we’d be caught in a national need to redefine the place of that identity in today’s increasingly global world. To do that, we all have to listen more and for a time, speak less, to the voices in Q2. We all have parts of us that reside in that part of the matix. We need to listen to our “other” counterparts. We must acknowledge, even embrace, our membership in this matrix, especially those of us who have for so long perceived inaccurately our hidden influences. This book is an invitation to become more a larger “you”, a more complicated “you,” simply by acknowledging in a more informed passionate way, the not so simple you that others see.

That’s what the stories in this book are all about. They are the stories of a regular white guy who became a teacher educator who considers himself an effective contributing member to the movement for social justice in America. What does that mean to me now? What did it used to mean to me? How have I changed? Why? How did I get here? How did the reality of being “an effective contributing member to the movement for social justice” shift as I became more aware of my own racial positioning? What did I learn about privilege when I recognized the importance of owning my privilege along the way? What did my pigmentation have to do with that? How am I at relative peace with who I am now even in the midst of so many who seem to be doing more? How has my perception of my contributions changed as I’ve brought more of my hidden areas into awareness, especially my social positioning? How do I rationalize my current work? That’s what I think this book is about. I think it is important that students know our own identity journeys as teachers. There is still work to be done. We can start with our own personal timeline. We can re-construct our life narrative to create a more accurate version of who we are in today’s world. We can re-construct our life narrative in a way that liberates our students to bring their story to the table. The world has changed. We need to be aware and honest about our place in it, our place with ourselves, and our place with each other. Here are pieces of my journey from the back to the front to the middle of my classroom. I hope it’s a good read for you. I hope our paths cross and that you feel free to branch off and travel your own road of understanding and recommitment to making your classrooms safer and more inviting for all your students. If this seems arrogant, forgive me, for I do not mean to speak from arrogance. Quite the opposite in fact. It takes enormous courage for me to even think this collection of stories might be a useful prompt for you to start considering your own. But we have less and less time to do the hard work necessary to achieve the kind of acceptance we and our students will need in our respective classroom settings. We have to begin with wherever we are, now. Thus I begin. Come along with me.

[i] “The Johari Window: A Graphic Model of Awareness in Interpersonal Relationships, http://www.augsburg.edu/education/edc210/johari.html

[ii] I “profess” at the University of Vermont. Under the leadership of President Daniel Fogel, Provost John Bramley, and its Board of Trustees, UVM has committed itself by its strategic plan to aggressively pursue the recruitment and retention of students whose background is other than “persons of non-color,” my favorite phrase for people who look like me.