By Luther Millison

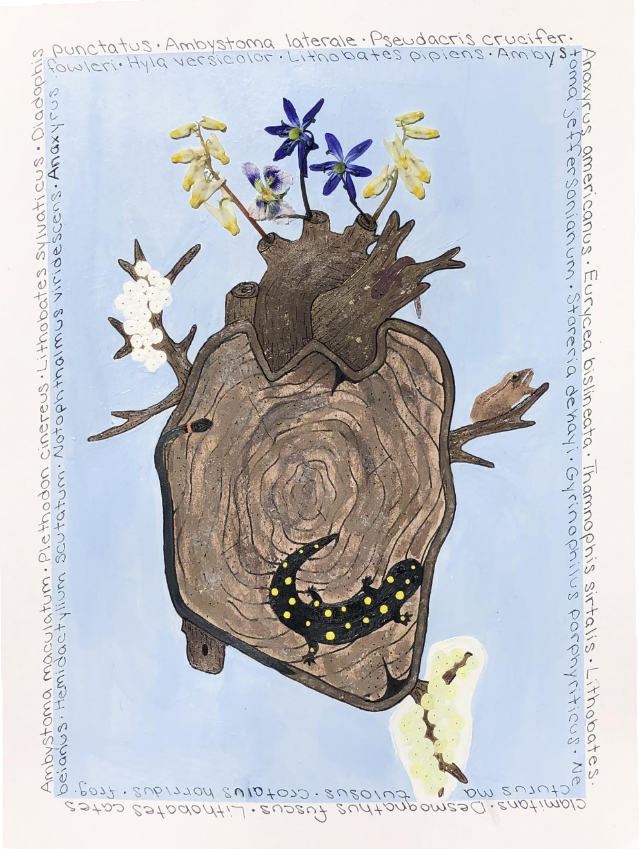

When we think about barriers to science, Jargon-filled technical writings and multi-level academic institutions may come to mind. But what about taxonomy? Taxonomy is the naming and classification of organisms. Scientific names are uniform to all but have you heard any common names that are not in your own language? What about how to decide a name for a new species when different species have different naming levels based on their prominence or usage value in societies.

Uniform names for species, be it scientific or common, are crucial for science communication especially when it comes to conservation efforts. Information such as human-wildlife interactions, historical range, observed behaviors, and human uses can all be gained from partnerships between communities and conservation scientists. But how is a local indigenous population supposed to communicate with scientists when scientists have little to no documentation of culture-specific folk taxonomy?

Joint PhD candidate at North West University (South Africa) and Hasselt University (Belgium) Fortunate Phaka is working on this problem. He along with Edward Netherlands, Donnavan Kruger, and Louis Du Preez published a paper last year. Their paper, Folk Taxonomy and Indigenous names for frogs in Zululand, South Africa documents their process collaborating with people in Zululand to document current Folk taxonomy for 58 frog species and standardize guidelines for future taxonomy in the isiZulu language, (and possibly other local languages).

So, how did this process start and what was it like? I interviewed soon-to-be Dr. Phaka about the spark for this study and how it got moving. Here’s what he had to say:

“In South Africa, a lot of people say culture is bad for wildlife or ‘people of color don’t care about wildlife’. However, for the majority of South Africans especially people of color, wildlife is intertwined with culture. There is no way we can be so close with wildlife and be bad for it.”

When he looked into cultural names for South African frogs, most species names were only in Afrikaans, English, and Latin. This leaves out the 9 Indigenous National languages of South Africa. After this, Phaka and his Colleagues began work on an English and isiZulu field guide based on what the community wanted to know about frogs right away. While developing this field guide, they began delving into the process of documenting isiZulu taxonomy.

Phaka and colleagues were starting fieldwork for this study in a very rural community surrounding Ndumo Nature Reserve. People from the community wondered what they were doing. These people knew about frogs and it turned out they wanted to be part of Phaka’s study. There were also two park rangers from the game reserve who were interested and wanted to be part of the study. Through these simple interactions and recommendations by participants, Phaka was able to recruit 13 interviewees for the study. These participants were all administered a questionnaire at an amphibian diversity workshop in Tembe Elephant Park. Participants were shown reference photos of the species in their areas and asked about the possible isiZulu names for those species. Because there were a few instances where one name was being used for several different species in the KwaZulu-Natal region, the interviewees had to establish some new ones. When the participants disagreed on a name or the reasoning for a name, they would deliberate until they reached an agreeable conclusion. Through this method (the full guidelines can be found in Phaka’s paper), new indigenous names were assigned to species previously sharing names and a new naming structure combining indigenous and modern taxonomy was put into practice.

A Scientist in Phaka’s position could easily take the credit for these new names and essentially steal this important intellectual property, but Phaka and his co-authors have been mindful to not appropriate any of this information. Phaka says, “when dealing with cultures, you are dealing with intellectual property. I want to be very careful to not steal any ideas/cultural knowledge. Luckily, new laws and university policies have helped make sure I’m not a bio-pirate. And South Africa’s department of environmental affairs is very helpful when it comes to culture and wildlife”.

A lot of people appreciate this research “especially members of previously excluded communities, they love the initiative and wonder how to help” says Phaka. “On the opposite side however, there are some seasoned scientists who want research to be done their way or no way.” Phaka calls these people ‘the gatekeepers of science’. “According them what I’m doing is not a scientific process and the indigenous names will not be scientifically acceptable.”

Despite the critics, Phaka stands by his work as an important way to take what has been neglected and show it to the world. In doing so, this science also helps represent and preserve South African and indigenous cultures while increasing the communication essential to conservation. Hopefully, studies like this can be adapted to promote and include communication with all kinds of communities for the benefit of conservation around the world.

Future plans

Fortunate M. Phaka will soon finish his Joint PhD at North West University and Hasselt University. He plans to Continue Indigenous taxonomy in the 8 other South African languages.

Phaka and colleagues’ paper can be found at: https://ethnobiomed.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13002-019-0294-3

And you can read more about Phaka and colleagues’ field guide here: http://youth4africanwildlife.org/south-africas-first-frog-handbook-written-in-an-indigenous-language/