By Sophie Kogut

Introduction:

There’s a new threat looming over amphibian populations – Ranavirus. Ranaviruses are a class of virus that pose an increasing threat to aquatic ecosystems, as infection can lead to devastating mass mortality events. A ranavirus is a large, double-stranded DNA virus that causes a hemorrhagic response, or excessive bleeding, in young toads and frogs which is often fatal. Ranavirus outbreaks may result in the decimation of entire generations of amphibian larvae. Even more concerning is that these viruses are not picky – they are capable of infecting amphibians, fish, and reptiles. Infection spreads rapidly through aquatic ecosystems because the virus is relatively stable. This is bad news, because according to disease ecologist Erin Sauer, “amphibians around the globe are already in peril”. Climate change, habitat destruction, the pet trade—the odds are stacked against many amphibian species, and it looks like ranavirus is just another enemy amphibians are up against.

What is behavioral fever?

When we get infected with a virus, one of our body’s immediate responses is to increase the body’s temperature, which results in uncomfortable sweating and chills: a fever. This signals to your immune system that something is wrong, and the immune system responds by kicking into overdrive: all hands on deck in an effort to destroy the pathogen. The initial fever is detected by the hypothalamus, which then directs your body to warm itself up. Unlike mammals, toads are ectothermic, meaning they must rely on their environment to regulate their body temperature. This is why you frequently see lizards basking in the sun, or salamanders cooling off under a log. When infected by a virus, toad immune systems are incapable of inducing a fever on their own. However, Sauer has been studying a clever adaptation that may allow herps to fight viruses: a behavioral fever.

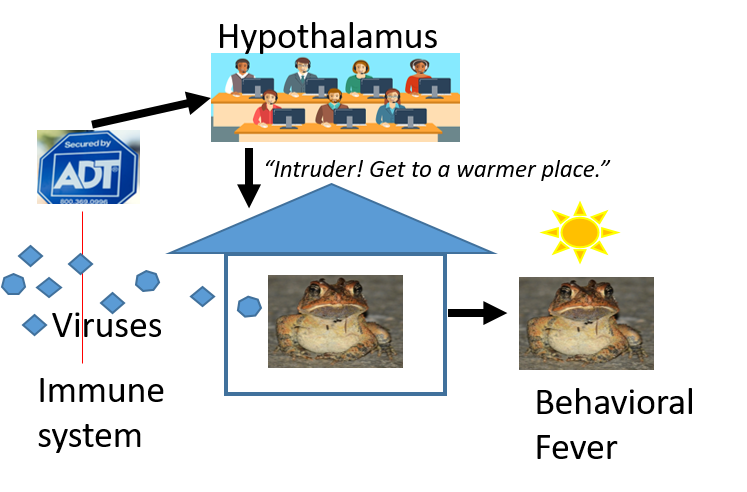

A behavioral fever occurs after the immune system detects the invasion of a pathogen, much like how a home security system detects an intruder. When the sensors on a home security system are triggered, a command center is alerted to the presence of the intruder; the command center will then alert the homeowner and provide instructions on how to respond. The hypothalamus in the brain of a toad acts like a command center, which, upon viral intrusion, instructs the toad to move to a warmer location, thus increasing its body temperature. This process is summarized below:

This phenomenon has been observed in many ectothermic species, but it does not occur with all types of pathogens. For example, infection by another infamous pathogen, chytrid fungus, does not induce toads to exhibit a behavioral fever. A behavioral fever is thought to kickstart the immune system in a similar way to fever in endotherms, where the fever acts as a messenger that facilitates a longer immune response, rather than a method to destroy the pathogens.

Dr. Sauer and her team designed an experiment to quantify the effects of behavioral fever on ranavirus. Their experiment yielded that adult Anaxyrus terrestris, or southern toads, are able to successfully reduce their viral load using this method, which is encouraging – to a point. Ranavirus is most deadly to younger animals, where large quantities of the virus may overwhelm the developing amphibian and result in a quicker death. Adult toads were tested using a method similar to COVID-19 testing: a swab sample was used to determine the presence of the virus, based on the quantity of viral DNA present. Unfortunately, the mouths of the younger toads were too small to be swabbed, so these frogs had to be analyzed post-mortem to determine viral presence; therefore, the results of this study apply more to adult toads.

Why should I care?

The changing climate may increase the frequency of disease outbreaks, so learning the strategies by which other animals fight these pathogens may prove to be extremely important in the context of endangered or threatened species. Also, there are serious economic and public health concerns when it comes to outbreaks—according to Sauer, there are “direct impacts on people getting sick, economic impacts on our [livestock] getting sick,” not to mention, “ these epidemic events could be an indicator that there’s something else going on in the ecosystem”. The current global pandemic is indeed a good example of how disruptive a microscopic virus can be. SARS-CoV-2 jumped from animals to humans and has since brought the world to its knees. Regardless of whether a pathogen is capable of affecting humans right now, it is essential that we continue to monitor the ecological patterns and consequences of these outbreaks.

Bottom line:

This study concluded that while cold-blooded toads could not fight infections like mammals do, they are able to change their behavior in a way that enhances their ability to combat disease.

What’s next:

More research is needed before we can determine if other species can use this mechanism to fight ranavirus in the way A. terrestris has. As the virus mutates and infects other species, behaviors and responses may shift, and it is imperative to keep studying them. In Wisconsin, Sauer is continuing to study the effects of urbanization on amphibian populations with respect to other diseases.

Where to find it: Sauer, E. L., Trejo, N., Hoverman, J. T., & Rohr, J. R. (2019). Behavioural fever reduces ranaviral infection in toads. Functional Ecology, 33(11), 2172-2179