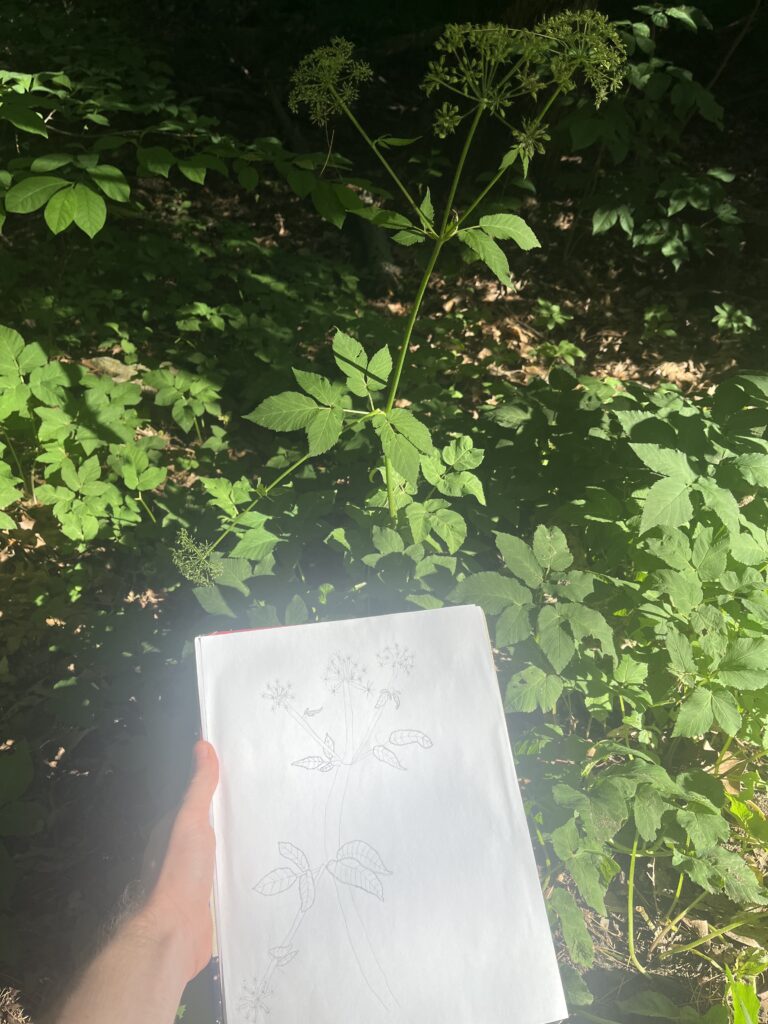

For the last entry in this blog, I have created a field guide to Woody Plants – both overstory and understory – at my site. Unfortunately, doing this in July means the buds are not well developed, so I was unable to get good pictures of them. As such, I will not be discussing buds, despite them being a good way to identify plants. In the making of this, I discovered several tree species I had not yet identified at this site, and truth be told, did not know how to identify. For most of the species in this guide, I was able to identify them just based on my own background knowledge, but for those that I could not, I used Seek by iNaturalist followed by quick google searches to confirm ID. Sites used to ID a plant will be mentioned in the entry for that plant, and all references can be found at the end of this blog entry. The plants are organized first by whether they are native or non-native, and then alphabetically by genus and species.

Native Species

Acer rubrum

Red maple is a deciduous overstory tree with opposite branching. Its leaves are smaller than most other maples, have 3 lobes, v-shaped sinuses, and serration on their edges. Red maple bark often has “target cankers” – areas of bark where it has grown in a circular pattern. It is usually a light grey.

Betula lenta

Sweet birch, or black birch, is a deciduous overstory tree with alternate branching. It has soft, serrated leaves. Sweet birch bark is grey and often not as peeled or broken as other birch species.

Carya glabra

Pignut hickory is a deciduous overstory tree with alternate branching. It has pinnately compound leaves with 5 leaflets (rarely 7) in an opposite pattern. It has grey bark that breaks into a lattice. It is easily confused with mockernut hickory – Carya tomentosa – but that tree has 7-9 leaflets per leaf.

Castanea dentata

American chestnut was once a widespread deciduous overstory tree, though individuals rarely reach that height anymore due to chestnut blight. This is the largest individual I have ever seen, at about 4 and half feet tall. It has alternate branching. When mature, the bark has deep furrows, though the stem of this chestnut would not be very helpful for ID. American chestnut leaves are fairly long – the largest here is about 7 inches – and obviously serrated.

Fagus grandifolia

American beech is a deciduous overstory tree with alternate branching. It can be identified by its naturally smooth, light grey bark. Its leaves have very slight serration. Beech trees are threatened by beech bark disease, which causes dark boils on the bark, an unfortunately common way to ID the tree.

Frangula alnus

Alder or glossy buckthorn is a deciduous understory shrub with oily looking leaves and round, dark berries. It is often confused with common buckthorn, but that plant does not have the characteristic glossy leaves. I don’t have any other ID tips, I just rely on the leaves and berries.

Gleditsia triacanthos

Honey locust is a deciduous overstory tree with alternate branching. It has pinnately compound leaves with many very small leaflets in an alternating pattern. Unfortunately, the lowest branches I could find were still too high up to get a good picture. Anecdotally, honey locust trees often have wild branching, though I have not found any literature to back this up.

Hamamelis virginiana

American witch hazel is a deciduous understory shrub identified by its wide, rough leaves. Notably, they are asymmetric where the leaf begins. The bark is smooth and grey.

Pinus resinosa

Red pine is an evergreen coniferous overstory tree with symmetrical branching. It has long needles in clusters of 2. It is most easily identified by its red, scaly bark – one of my favorite tree barks. Unfortunately, red pines are dying mysteriously in recent years. There are already a number of dead mature trees in this park, and I have not seen any regeneration, hence why I could not get a good picture of the needles.

Pinus strobus

Eastern white pine is an evergreen coniferous overstory tree with symmetric branching. It has smaller needles than the red pine and they grow in bundles of 5 – though finding bundles with fewer is not uncommon as some fall out. Its bark is a deep brown with obvious furrows. The brown can vary from a reddish hue to a dark hue.

Prunus pensilvanica

Fire or pin cherry is a deciduous overstory tree with alternate branching, though, according to the US Forest Service, it rarely lives more than 35 years and often will not be competitive in established forests. It can be identified by bright orange lenticels on the bark and long, glossy leaves with fine serration. It is easily confused with black cherry when young, but it has brighter lenticels and longer leaves. Fire cherry fruits are bright red and delicious.

Prunus serotina

Black cherry is a deciduous overstory tree with alternate branching. Like the fire cherry, it has long, glossy leaves. When mature, black cherry bark is a dark grey – nearly black – and very flaky. It is often called “burnt potato chip bark”. Its fruit is a dark purple when ripe, and also delicious.

Prunus virginiana

Choke cherry is a deciduous understory shrub with alternate branching. It has shorter, wider leaves than black and fire cherry. It also has lighter bark with less prominent lenticels. Its fruit is also a dark purple when ripe, but is bitter.

Quercus alba

White Oak is a deciduous overstory tree with alternate branching. Its leaves have the traditional oak shape with rounded lobes. They can have deep sinuses like these ones or very shallow sinuses, like those in the red oak below. It has very light bark with thin, deep furrows. When mature, its bark can take on a “cheese grated” appearance – especially at the base.

Quercus rubra

Northern red oak is a deciduous overstory tree with alternate branching. It has the traditional oak leaf shape with pointed lobes. The sinuses can be shallow like these ones, or deep like those of the white oak above. Its bark tends to have wide furrows with a red hue inside them, though this red hue is not always present.

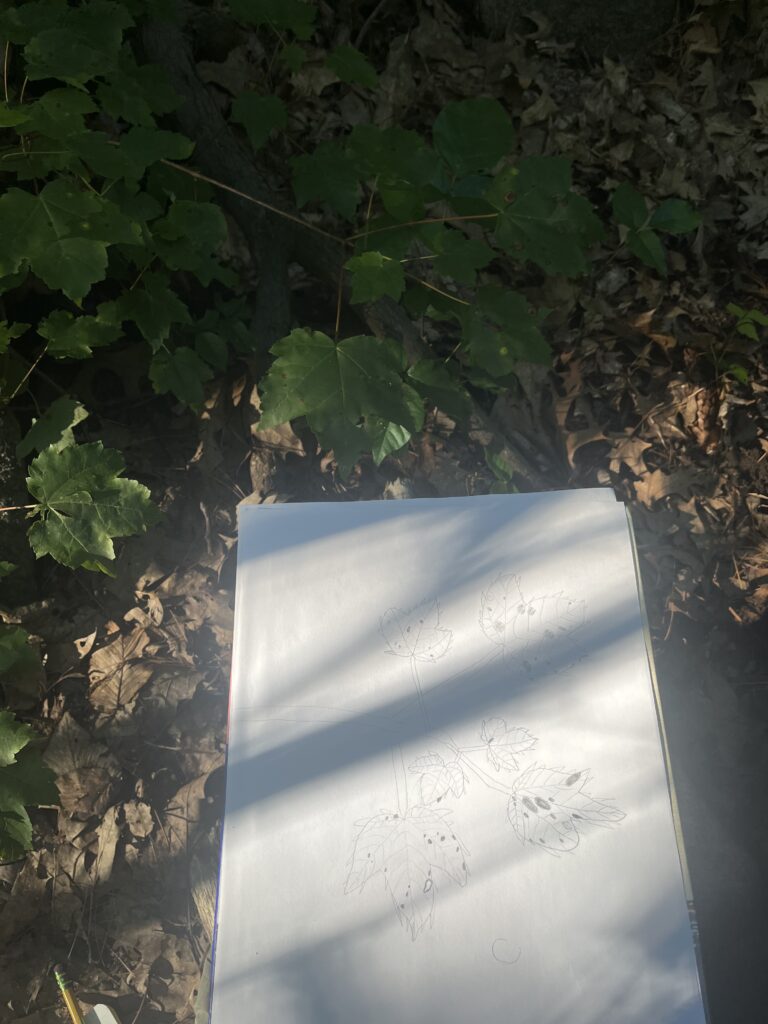

Sassafras albidum

Sassafras is a deciduous plant that usually grows as an understory shrub, but can reach the overstory. It has alternate branching. Its leaves are distinguished by the “glove” shape. Leaves can have a single sinus or two, as shown in the image, but not all leaves will have a sinus. The bark has deep furrows that form a lattice work.

Tsuga canadensis

Eastern hemlock is an evergreen coniferous overstory tree with symmetric branching. It has small needles that grow relatively flat and roughly parallel to the ground. Its bark tends to be a bright brown and somewhat scaly.

Ulmus americana

American Elm was a tree I did not know how to identify. According to the US Forest Service, it a deciduous overstory tree with alternate branching. The leaves are double toothed, 2-5 inches long, and 1-3 inches wide. Notably, the leaves are also very rough. The USFS says the bark is dark grey and deeply furrowed, though the bark on this individual is lighter. That may just be due to it still being young.

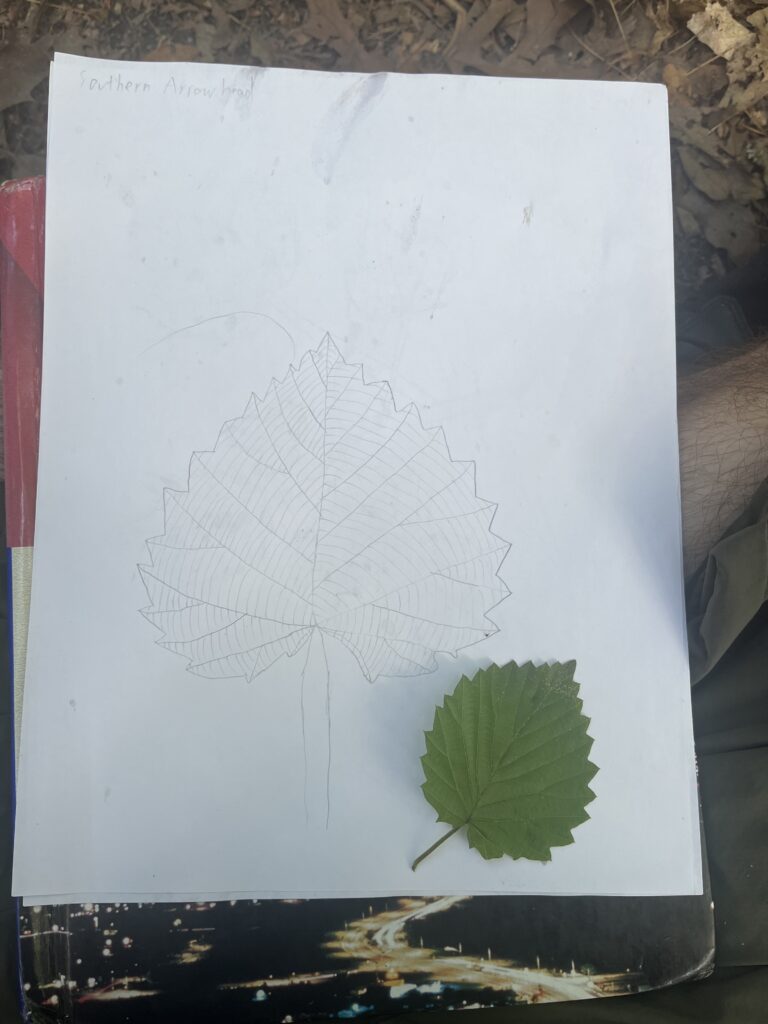

Viburnum dentatum

Southern arrowwood is a deciduous understory shrub with opposite branching. It is easily identified by its leaves. They have the shape of an arrowhead and a prominent lattice of veins that look like a web.

Non-Native Species

Acer platanoides

Norway maple is a deciduous overstory tree with opposite branching. It has enormous leaves with 5 – 7 lobes. It has long furrows in its bark. It is easily confused with sugar maple, though it has larger leaves, sugar maple leaves do not have 7 lobes, and mature sugar maple bark forms plates while Norway maple bark does not. According to the US Forest Service, it is native to continental Europe and Western Asia, having been introduced to North America in the mid 1700s.

Fagus sylvatica

European beech is a deciduous overstory tree with alternate branching. It has very similar bark to the American beech – light grey and smooth. According to the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, it is also affected by beech bark disease, resulting in the same dark boils in the bark as on American beeches. The main difference is the leaves, which are rougher, glossier, not as obviously toothed, and rounder than American beech leaves. According to Yale University, it is native across much of continental Europe and Southern England.

Picea abies

Norway Spruce is an evergreen coniferous overstory tree with symmetric branching. It has thick bunches of needles forming an ovate shape – not quite cylindrical. The canopy is typically pyramidal and reaches almost to the ground. Its bark is brown and scaly. According to the US Forest Service, it is native to Northern Europe, as well as several mountainous regions in Central Europe.

Robinia pseudoacacia

This was another species I did not know how to identify. It is a deciduous overstory tree with alternate branching. It has pinnately compound leaves with larger but fewer leaflets than the honey locust. According to the US Forest Service, the mature bark is “thick, deeply furrowed, scaly, and dark brown.” The only individual I found was still very young. Its native range is debated, and the USFS has a very detailed breakdown of the native range, but the general consensus, according to the USFS, is that there are two regions to which it is native: Central Appalachia and further West in Arkansas and Oklahoma.

Conclusion

This was a lot of fun to put together. I got to practice my identification skills of trees and shrubs I already knew, and found several that I did not know. I wish I could have included pictures of the buds and gone into detail about them, but it is the wrong season for that.

References

14, K. W. on A., & 19, K. W. on A. (2019, February 6). Yale University. European Beech | Yale Nature Walk. https://naturewalk.yale.edu/trees/fagaceae/fagus-sylvatica/european-beech-95

Beech Bark Disease. Beech Bark Disease | | Wisconsin DNR. (n.d.). https://dnr.wisconsin.gov/topic/foresthealth/beechbarkdisease#:~:text=Species%20impacted%20include%20American%20beech,Oriental%20beech%20(Fagus%20orientalis).

Picea abies. (n.d.). https://www.fs.usda.gov/database/feis/plants/tree/picabi/all.html#:~:text=DISTRIBUTION%20AND%20OCCURRENCE,-SPECIES%3A%20Picea%20abies&text=GENERAL%20DISTRIBUTION%20%3A%20Norway%20spruce%20is,in%20northern%20Russia%20%5B50%5D.

Prunus pensylvanica L. (n.d.). https://www.srs.fs.usda.gov/pubs/misc/ag_654/volume_2/prunus/pensylvanica.htm

Robinia pseudoacacia. (n.d.). https://www.fs.usda.gov/database/feis/plants/tree/robpse/all.html

Species: Acer platanoides. (n.d.). https://www.fs.usda.gov/database/feis/plants/tree/acepla/all.html

Ulmus americana. (n.d.). https://www.fs.usda.gov/database/feis/plants/tree/ulmame/all.html#:~:text=In%20the%20South%2C%20American%20elm,in%20river%20bottoms%20and%20terraces.