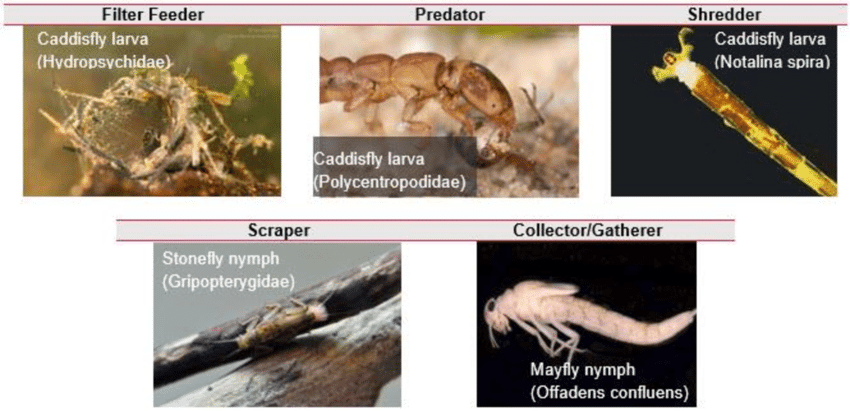

Macroinvertebrates are small organisms that lack a backbone and are common in aquatic settings. Streams can support diverse communities of macroinvertebrates. Within these communities, each species has different traits, habits, and habitat preferences. Due to this widespread diversity, macroinvertebrates that live in freshwater are classified into six Functional Feeding Groups (FFG). Each FFG is based on the feeding morphology, or the basic shape of their feeding appendages rather than by their relation to other species. There are five basic FFG: shredders (eat leaf litter and coarse particulate organic matter), scrapers (eat algae and other items they “scrape” off rocks), collector/gatherers (which collect and consume fine particulate organic matter from the bottom of the stream), predators (which consume other consumers), and filterers (which use their appendages to filter and consume fine particulate organic matter from the water). While these groups are mostly comprehensive, some species don’t fully fit into any of these groups and are categorized as “others”. West Virginia Government, 2024). These feeding habits also make macroinvertebrates an important step in transferring energy from primary producers and particulate organic matter to consumers at a higher trophic level, such as predatory fish. Their place in the trophic system means that any changes to their abundance or diversity of FFGs can have widespread impacts both on species that they consume and are consumed by (Cummins, 2016).

Example species of the five main macroinvertebrate Functional Feeding Groups. (Coleman et al., 2021).

Macroinvertebrate populations can be affected by a variety of factors from stream water quality to the morphology, or shape, of the stream. Beaver activities such as felling trees and digging canals can change stream morphology (Brazier et al., 2020).

These changes can have a variety of impacts on macroinvertebrate communities within these streams but until 2019, the nature of these impacts has been relatively unstudied in North America, particularly in the West. In 2019, the study “Beavers alter stream macroinvertebrate communities in north-eastern Utah” by Susan Washko, Brett Roper, and Trisha B. Atwood compared the macroinvertebrate communities in beaver altered streams to unaltered streams.

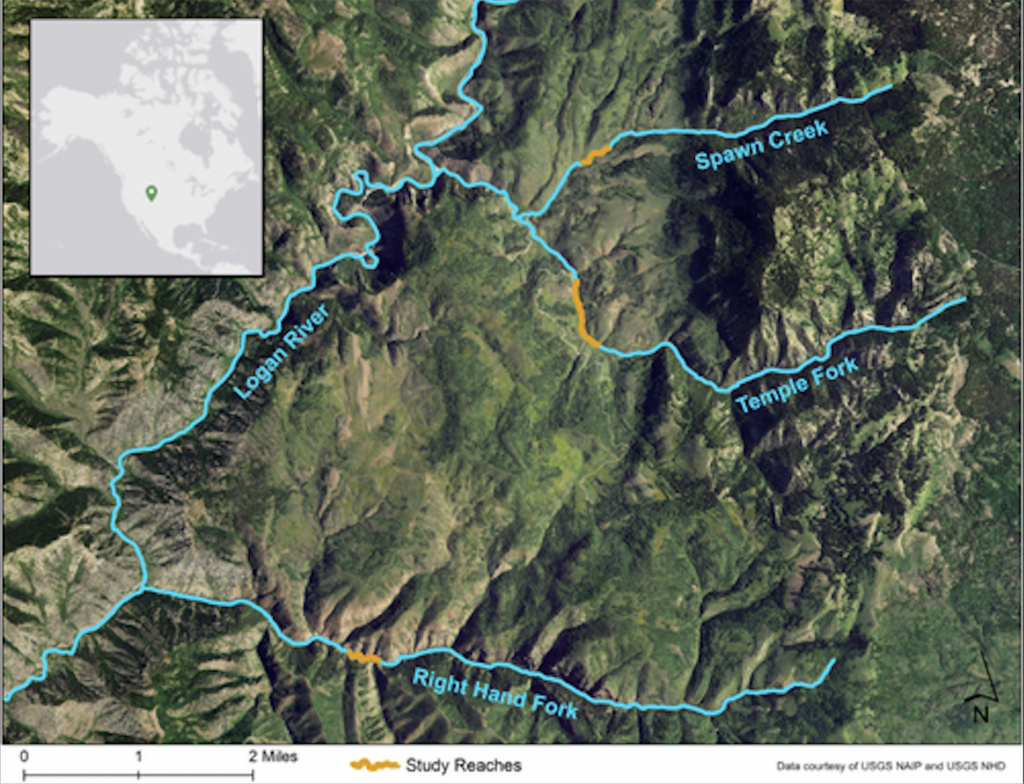

Three main tributaries to the Logan River (Right Hand Fork, Spawn Creek, and Temple Fork) were chosen to model the possible variety of responses, as each stream had a distinguishing characteristic. Temple Fork was the widest stream (average width of 4.0 m). Right Hand Fork was the second widest (average width of 3.9 m) but the most confined stream. Spawn Creek, the least wide stream (average width 1.8 m), was encompassed by a 67-ha cattle exclusion fence. The other large difference between the three streams was the biotic, or alive, aspects of the stream. Only Right Hand Fork had submerged macroinvertebrates present. However, the other two streams had more diverse fish populations, including brown trout (Salmo trutta) which is invasive in the area. In comparison, the fish population of Right Hand Fork is mainly Bonneville cutthroat trout.

Spawn Creek, Temple Fork, and Right Hand Fork, three tributaries to the Logan River. (Washko et al., 2019).

Each of the three tributaries was sampled in two areas: one area, classified as the “pond area” where the beavers had established and the other area, above the ponds, classified as “lotic reaches”. The lotic reach areas had faster water flow, though were shallower and had larger substrates (cobble). In each stream, five samples were taken from lotic (flowing) areas, and five samples were taken from a nearby beaver pond for a total of 30 samples. However, one sample was left out in the final analysis due to sampling error.

In addition to the macroinvertebrate samples collected, each location was sampled for “environmental characteristics” including elevation, water temperature, levels of dissolved oxygen, velocity, and substrate size. For each stream, each characteristic was averaged separated by pond and lotic reach area.

In comparison to the multiple sampling events for environmental characteristics, macroinvertebrate samples were only taken once per each lotic reach and once per each beaver pond. The lotic reaches were sampled using a surber sampler while the ponds were sampled using a sweep net. This gear and lack of replications were specifically chosen to limit the amount of non-natural disturbance to the communities. Each sample was grouped by taxa and then dried and weighed. Based on these biomass weights and density calculations, the dominant taxa of each sample were found. The number of EPT (Ephemeroptera, Plecoptera, and Trichoptera) taxa was also specifically calculated. EPT taxa are notoriously sensitive to pollutants, so the abundance of these taxa within a stream is often used as an indicator of the water quality. The groups were sorted at the highest level by taxa, they were further identified by the dominant FFG and whether their primary habitat was lentic (still) or lotic (flowing).

Surber net sampling of a stream. (Department of Conservation, 2013).

Sweep net sampling. (Manaaki Whenua Land Care Research, 2024).

The presence of beavers did impact macroinvertebrate communities in the study streams. In all streams, there were significantly higher macroinvertebrate densities, biomass, and densities of EPT taxa collected in the lotic regions than in the pond regions. EPT taxa specifically were also denser in the lotic areas. Additionally, there were more taxa of the scraper FFG in the pond sections than in the reach areas.

These results are believed to be due to changes resulting from the dam building process. However, these changes can vary by stream. The primary reason for these changes is proposed to be a decrease in sediment size in beaver ponds. Smaller sediment sizes can decrease interstitial (or “in-between”) spaces, providing fewer places for macroinvertebrates to live. There may also be less substrate for periphyton (communities of algae and fungi), which can explain the decrease observed in the scraper FFG (Washko et al., 2019).

The results of this study are in contrast to beaver pond-induced effects on fish communities. Beaver ponds were found to increase habitat diversity for fish (Hägglund & Sjöberg, 1999). While beaver dams might have an overall positive effect on fish communities, the negative impacts on macroinvertebrates, an important food source, should be further examined. This contradiction may have unobserved but influential impacts on the ecosystem overall.

References

Coleman, Daniel, Andrew John Brooks, Lauren MacRae, and Tim Haeusler. 2021. The Influence of Unregulated Tributaries on Macroinvertebrate Communities in a Regulated River. Technical Report.

Cummins, Kenneth W. “Combining Taxonomy and Function in the Study of Stream Macroinvertebrates.” Journal of Limnology 75, no. s1 (March 22, 2016). https://doi.org/10.4081/jlimnol.2016.1373.

Department of Environmental Protection. 2024. “Functional Feeding Groups.” https://dep.wv.gov/WWE/getinvolved/sos/Pages/foodweb.aspx#:~:text=The%20major%20functional%20feeding%20groups,using%20a%20variety%20of%20filters%3B.

Gray, Duncan. Rep. 2013. Freshwater Ecology: Quantitative Macroinvertebrate Sampling in Hard-Bottomed Streams Vol. 1.

Manaaki Whenua Landcare Research. 2024. “Sampling Tips”. Freshwater Invertebrates Guide. https://www.landcareresearch.co.nz/tools-and-resources/identification/freshwater-invertebrates-guide/sampling-tips/

Washko, Susan, Brett Roper, and Trisha B. Atwood. “Beavers Alter Stream Macroinvertebrate Communities in North‐eastern Utah.” Freshwater Biology 65, no. 3 (December 15, 2019): 579–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/fwb.13455.