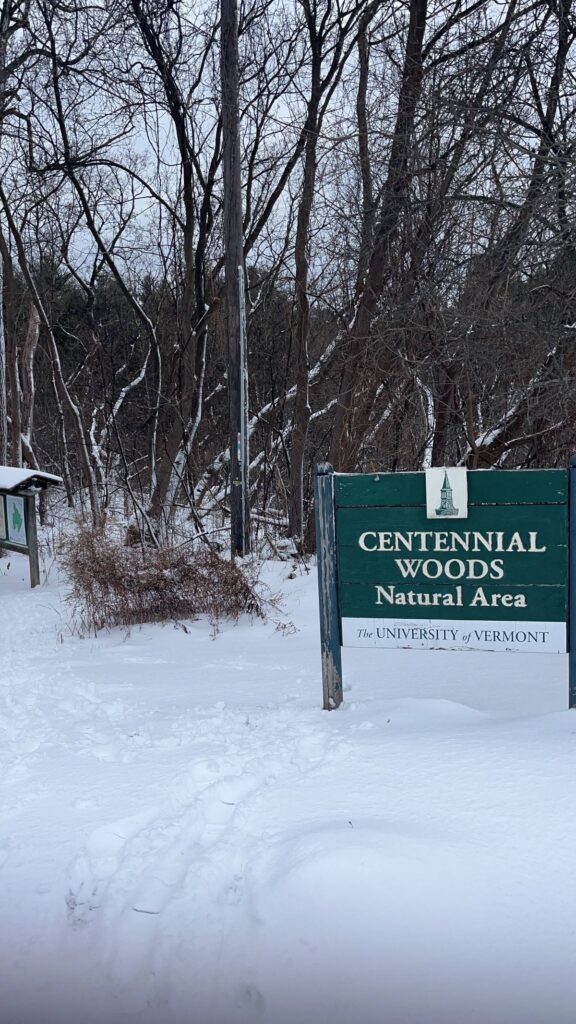

On May 1st, I visited my phenology spot for the final time this semester. I haven’t had the opportunity to visit this spot since the more recent warmer weather and once I finally did, there were many changes that had occurred.

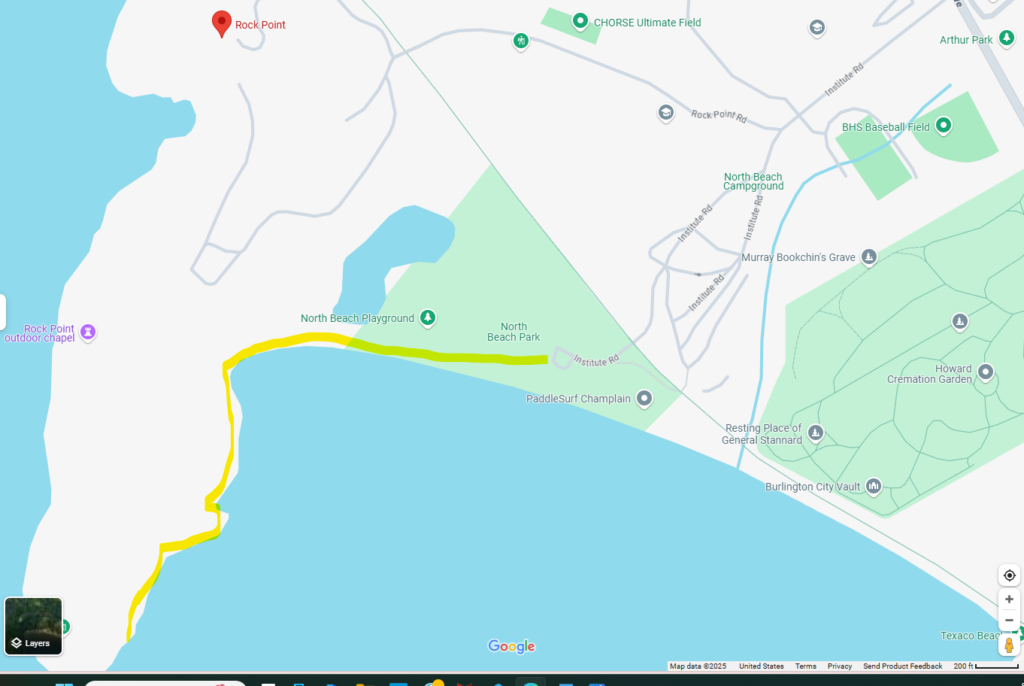

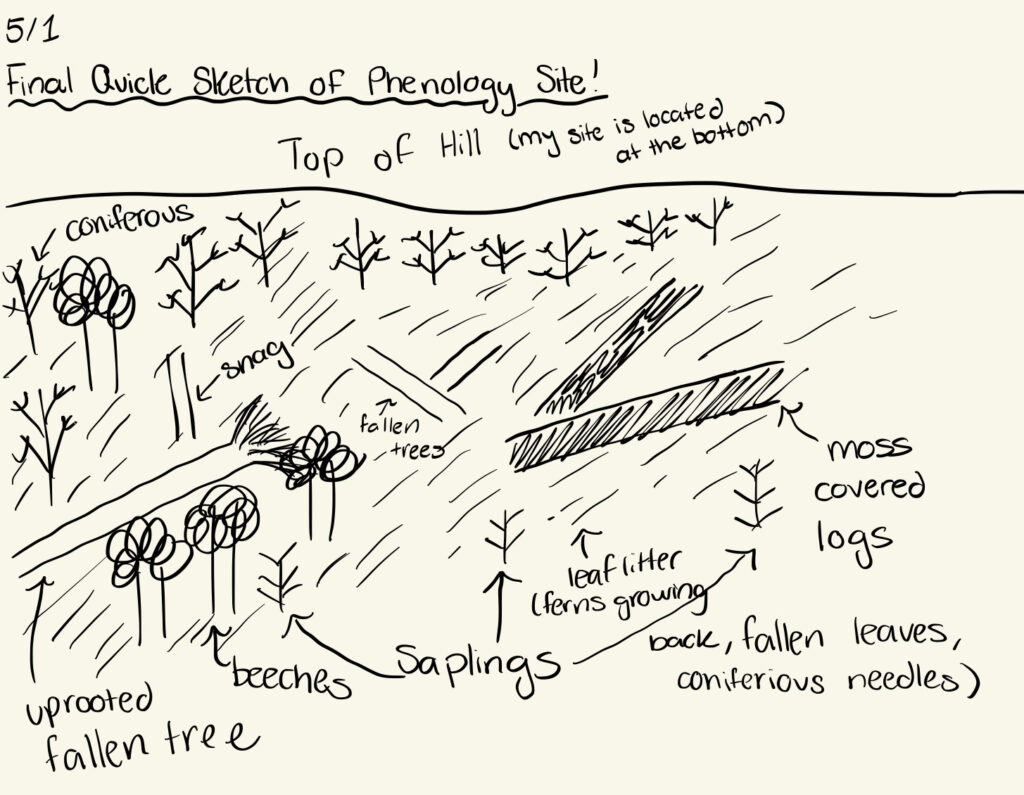

(sorry for my horrible artistic abilities)

Coming back to my site, it was indicative that spring had sprung here!

The ferns that covered most of the ground, an aspect of my site that helped define it and what made me choose the spot in the first place, had almost completely vanished. Instead, fallen, dead leaves and coniferous needles covered the ground with new fiddleheads and other ferns growing in their place.

Moss began to cover almost all of the fallen tree trunks exponentially more than it had before. Additionally, there were new fallen trees towards the back left of my site, which also began to accumulate moss.

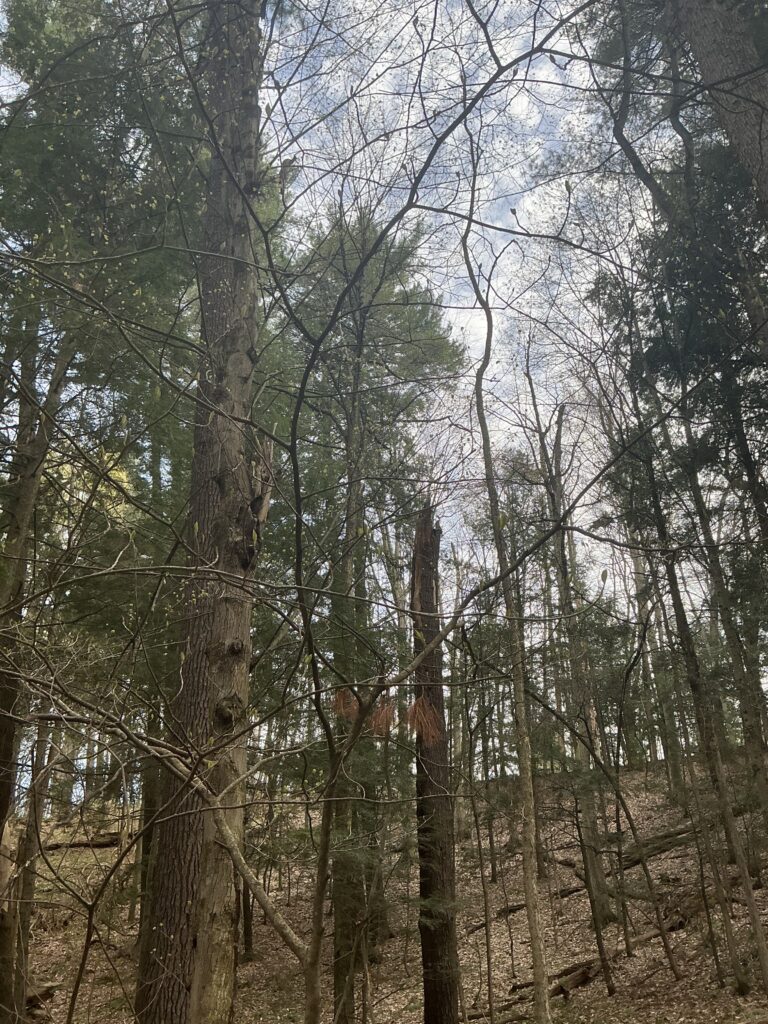

The trees were still flowerless and leafless, but they began to bud.

Additionally, I noticed a rise in saplings throughout my site, specifically American Beeches that were beginning to leaf.

In addition to signs of spring coming in through the presence of tree budding and changes in plants, there were also indications of spring coming from animal signs. There were many bird chirpings, indicative of spring. However, given the proximity to the airport and other human development, the bird sounds were very faint and drowned out by human noise more often than not.

My Overall Connection to the Site

Overall, there were several components of my site that I would view as staple landmarks that connected me deeper to my place.

Firstly, a minor landmark: the ferns.

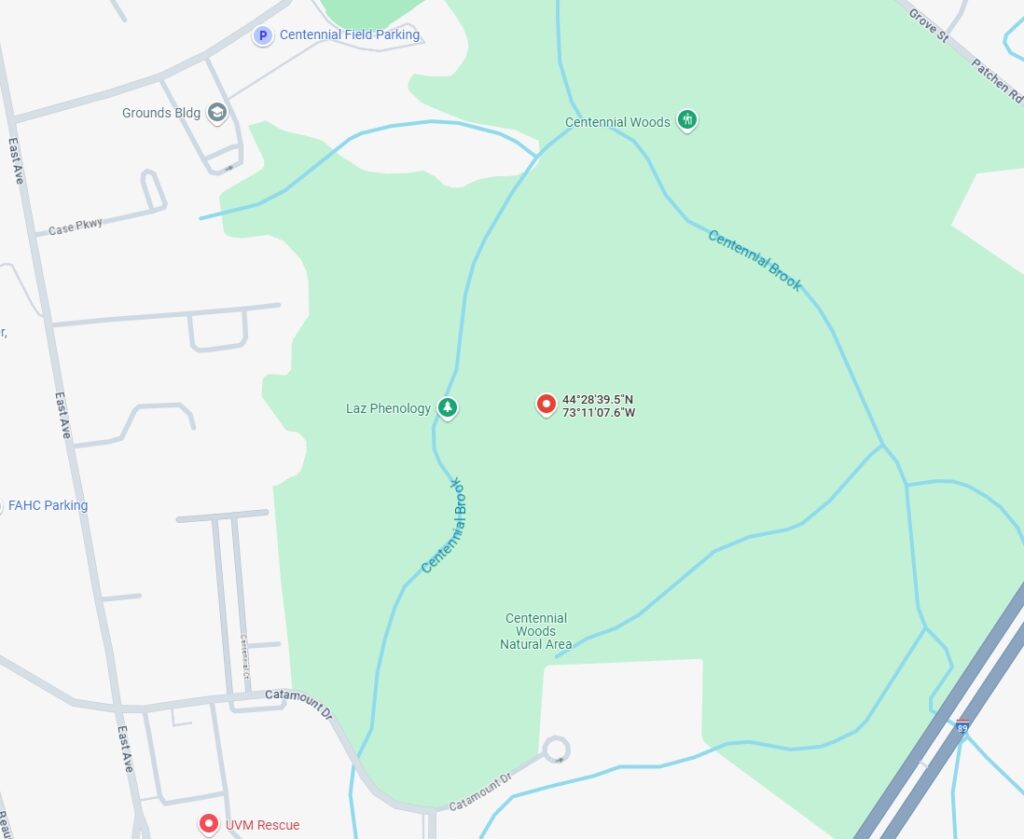

The ferns that covered the entirety of the site were what initially drew me to the site. Whilst Centennial had ferns throughout the forest, this area stood out to me for its ground being completely covered in ferns. When I first came to this area, the ground cover of ferns with the tall coniferous and Beech trees made the site feel incredibly mystical. It was something that defined this site for me and stood out to me from the rest of the forest.

This showcases the coverage of the ferns before versus now and why they are such a prominent landmark of the area

Secondly, a major landmark: Uprooted fall tree

At the bottom of the hill of my site sits this large fallen uprooted tree which became a distinct feature of the area.

In addition to this, some minor landmarks of this area were the surrounding fallen trees that encompassed the entire site.

Culture & Nature

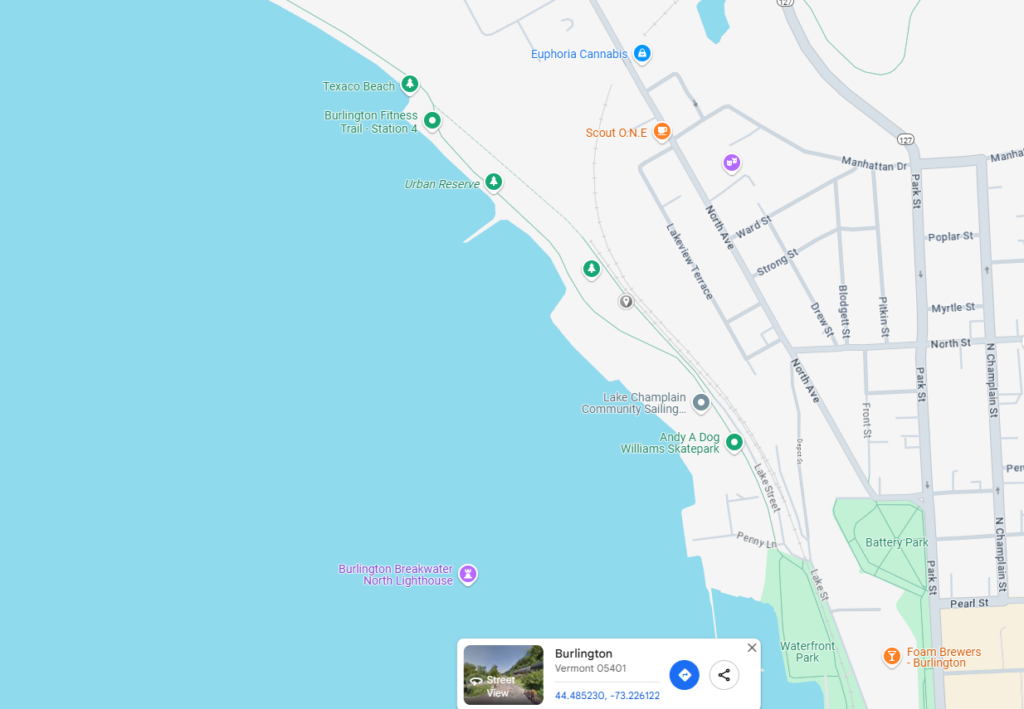

For Centennial as a whole, I think the role of culture comes in through the recreational use of the forest. The forest is accessible to a very urban area and my site is indicative of this as well. My site is located just off the main trail and isn’t too far into the forest. This means that this area is accessible to people and specifically UVM students and faculty. Every time I visit this site I come across families hiking with dogs, people on runs, students or parents with young children. Additionally, close to my site, there is typically a hammock hanging. The modern culture of this area is recreation and this sense of place and calmness that sitting in this natural area brings. Since Burlington is so urbanized, Centennial brings this peaceful, natural escape from that, where people can reconnect with nature.

But historically, there has been this connection between culture and nature in this area in a very different way. The original inhabitants of Centennial Woods were the Abenaki people. They practiced subsistence hunting and had this deep connection with Earth and coexisted with the natural world in a very healthy way. Post-colonialism, Centennial Woods and many natural areas in the US changed from this healthy coexistence between humans and nature. In places like my site, we see this increased noise and physical pollution, limiting biodiversity in the site. And due to this shift in culture as a result of colonialism, we see this change from having this area be a priority to connect with, to then utilizing this area as an escape from the harsh industrialized world we live in today. However, as we see with noise pollution to my site, even these “natural” areas become contaminated with the effects of this post-colonial view of nature and environment being separate.

Final Thoughts

Overall, my connection with this place is very ambivalent. I am not entirely sure I would consider myself part of my place.

On the one hand, I think the proximity of my site of being closer to the edge of the forest, exposing it to much more noise pollution, impacts this lack of connection. Oftentimes throughout the semester, I found myself wishing I chose a different site due to this. The constant airplanes flying over, made it impossible for me to sit in silence in my site and even be able to carefully listen for bird noises. In fact, this final visit, I heard several faint bird chirpings but was completely unable to identify them due to the constant aircraft activity. Due to this noise pollution, it made the site unsettling and decreased the levels of wildlife activity through the area. Additionally, my site is located in a very hilly section, making most critters against traveling through, meaning there wasn’t much activity throughout the year. Despite this, this site did open up my realization of the prevalence of noise pollution in Burlington (and surrounding areas) and how that can ruin even the smallest number of natural areas we have and ruin this natural “escape” many people utilize forests such as Centennial for.

That being said, I appreciate this site for making me become more in tune with noticing the smaller details that many people overlook when in natural areas. I began to find myself observing things closer and closer every time I came back in search of something new. This natural curiosity is something I cherish given to me from this site. I found a deeper love and appreciation for ferns and moss which are often details people overlook and instead look at the bigger species such as the overstory make-up.