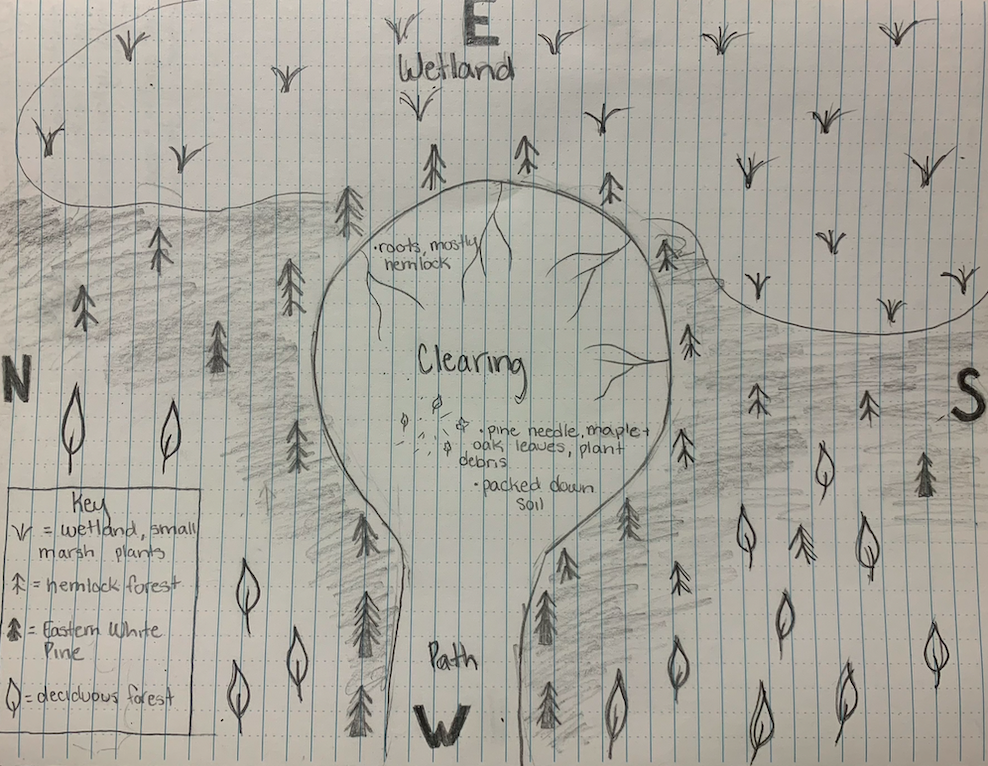

On this warm, sunny May day, my site in Centennial Woods is the greenest I’ve seen since early last fall. The yellow birches, red maples, and small bushy plants like barberry are fully leafed out. The understory is beginning to come in as well, with all of the fiddleheads nearly unfurled. The wetlands as well are appearing more green and full of life by the day.

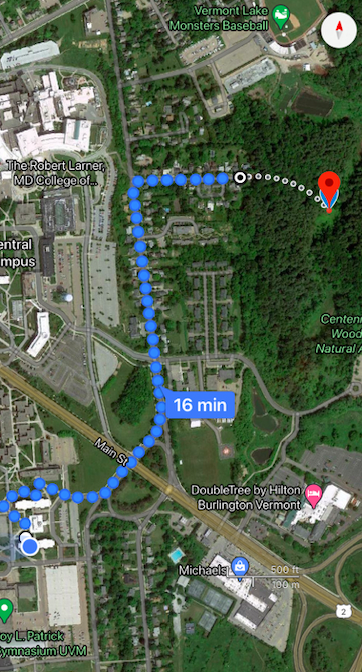

Humans are intertwined with this ecosystem in many different ways. Centennial Woods has been utilized by humans for a variety of things since it was reforested and acquired by the University from the late 1800’s into the early 20th century. Now, however, it is mostly visited by humans for its spiritual and emotional value. My site is particularly designed for this purpose, as it is a human-made clearing within a circle of hemlock trees. The unique design of my site draws people to it all the time. Throughout the course of visiting my site a fort was partially built. There was also a time that someone was sitting in my site when I arrived and I had to find somewhere else to settle. This didn’t bother me though because there is a very mossy fallen log not far from my site that I often visit to meditate on or look for mushrooms. As a COVID-college freshman, I found visiting my site revitalizing, as it always felt like an escape from campus and the stress of school. I appreciated that in just 10 minutes I could find a place that felt secluded and wild. That being said, I always see people in Centennial Woods, but that is part of its draw as well, it is a place where humans and nature connect everyday. Still though, I was always able to spot new plants, animals, birds, insects and fungi on my visits. Connecting to the specific species in my site helped me feel more like a part of it and less like a visitor with each stay.