Reflecting on a Year of Change

Because the last time I had visited my phenology spot was in January, when Shelburne Pond was frozen over and there was still around a foot of snow on the ground, visiting this place at the onset of Vermont spring was an awesome way to end a year of phenological observations. As we drove up to the dock, it was wonderful and refreshing to see the sun shining again on the vibrant blue pond, as well as some new green tree foliage and vegetation. Upon closer observation, we noticed that the Northern red oaks towering in the canopy, as well as some American beech and elm in the understory, had regained their vibrant greenish-yellow leaves. The Eastern white pines and Northern white cedars had also taken on a brighter green coloration, as the winter season had come to a close. The majority of the understory had yet to regain its leaves, but we did observe some prominent bud breaking. Although we did not hear or see many signs of wildlife, the warmer temperature brought numerous other public visitors to the pond while we were there, many with fishing supplies and kayaks.

The Transitions:

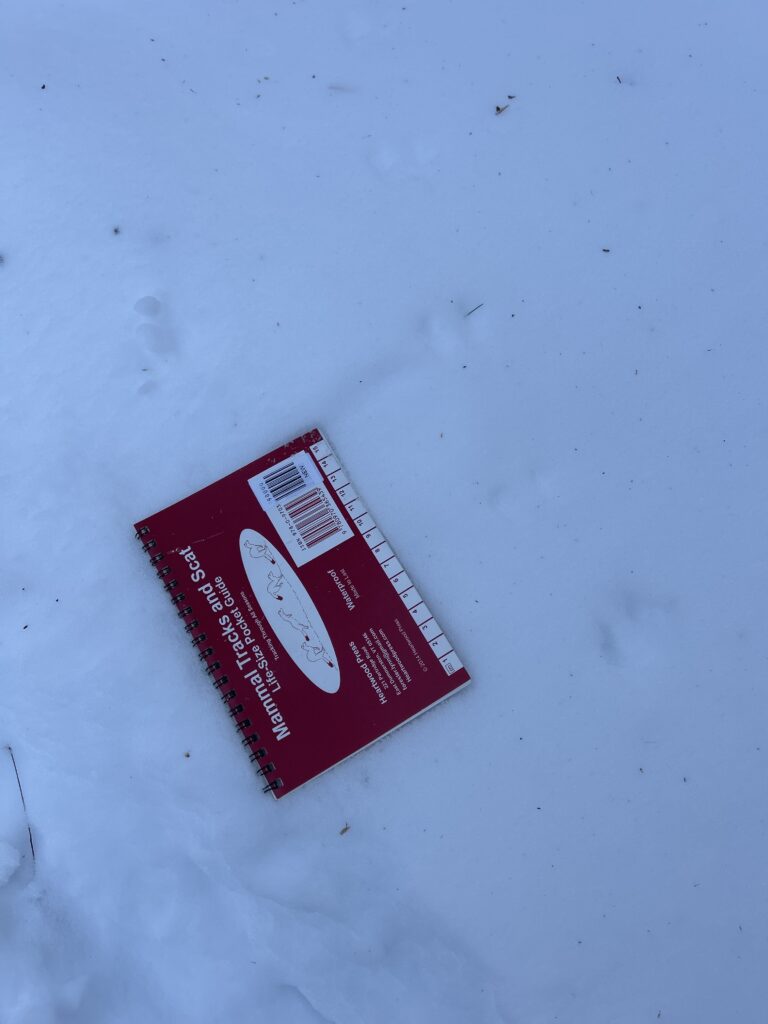

Reflecting on how this site has changed over time, the clearest transitions have been seen in the foliage. During our first visit in October, the leaves had just begun to change into their bright orange and red hues, and the vegetation was dense and shrubby. Within just a few weeks, the trees lost the majority of their foliage, aside from the few conifers in the area, and the site appeared to be much more bare. After about a month, Shelburne Pond in December had become covered with snow, and almost all of the understory vegetation had become completely barren. The snow-covered vegetation that remained became dark and brown, while the cattails and aquatic vegetation stood frozen in the few patches of ice near the pond’s shoreline. Although there weren’t many changes in the vegetation, Shelburne Pond became covered with even more snow and ice by late January. During this visit, we observed numerous signs of wildlife compared to previous visits, thanks to some clear animal tracks in the snow. We even got to walk out onto the frozen Shelburne Pond and view our phenology spot from a different perspective! Now that a few months have passed, the characteristic spring phenological changes have begun, such as the bud-breaking and coloration changes we observed today. Overall, coming back to this spot throughout the year has been such a cool way to understand phenology and the seasonal cycles of both terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems. I am eager to return at the end of August to see what the summer season looks like at Shelburne Pond!

The Landmarks:

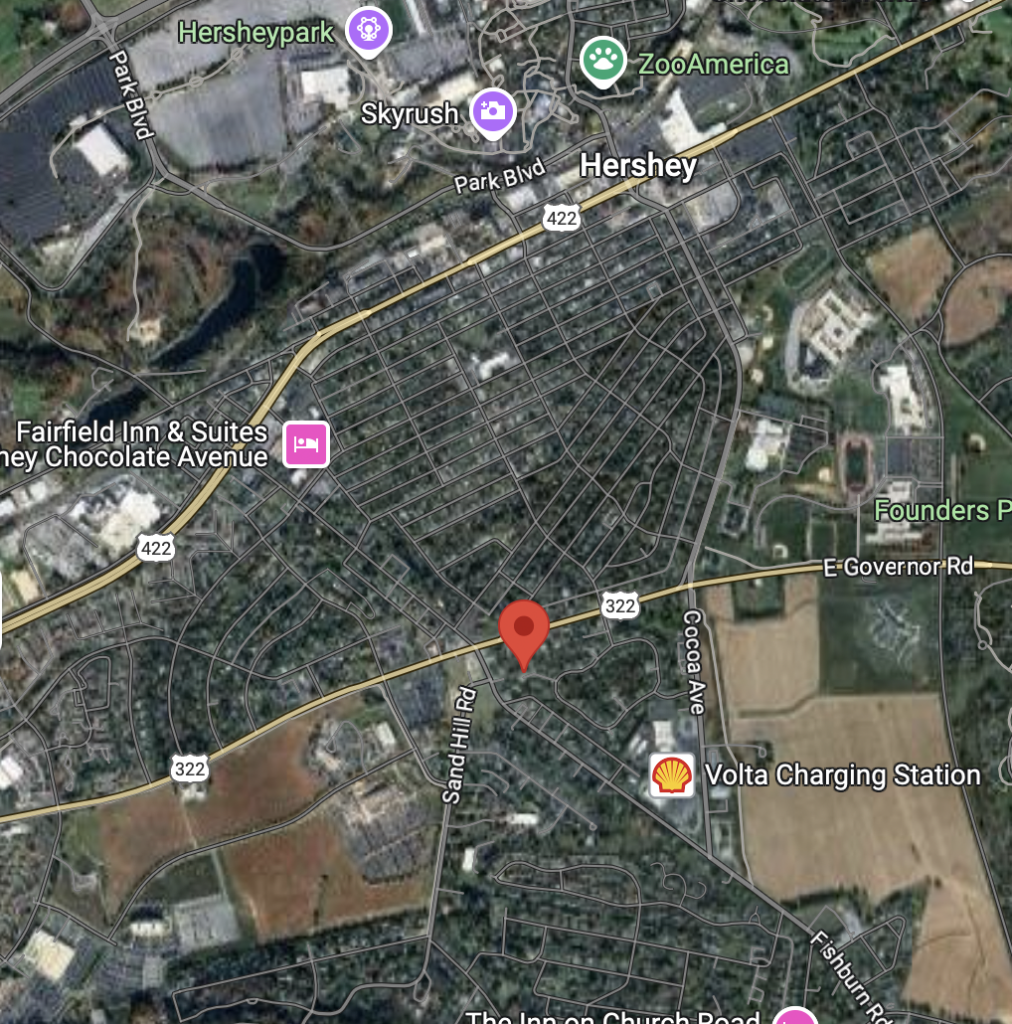

The dock!

The dock has been one of my favorite parts of our phenology spot. We love walking out to the end and viewing the vastness of the pond and forest on all sides. There are spectacular views of the mountains and farmlands from the dock as well!

The rocks!

A few large stones line the pathway down to the dock and the pond, and these have made great spots to sit and observe our phenology spot from.

The conifers!

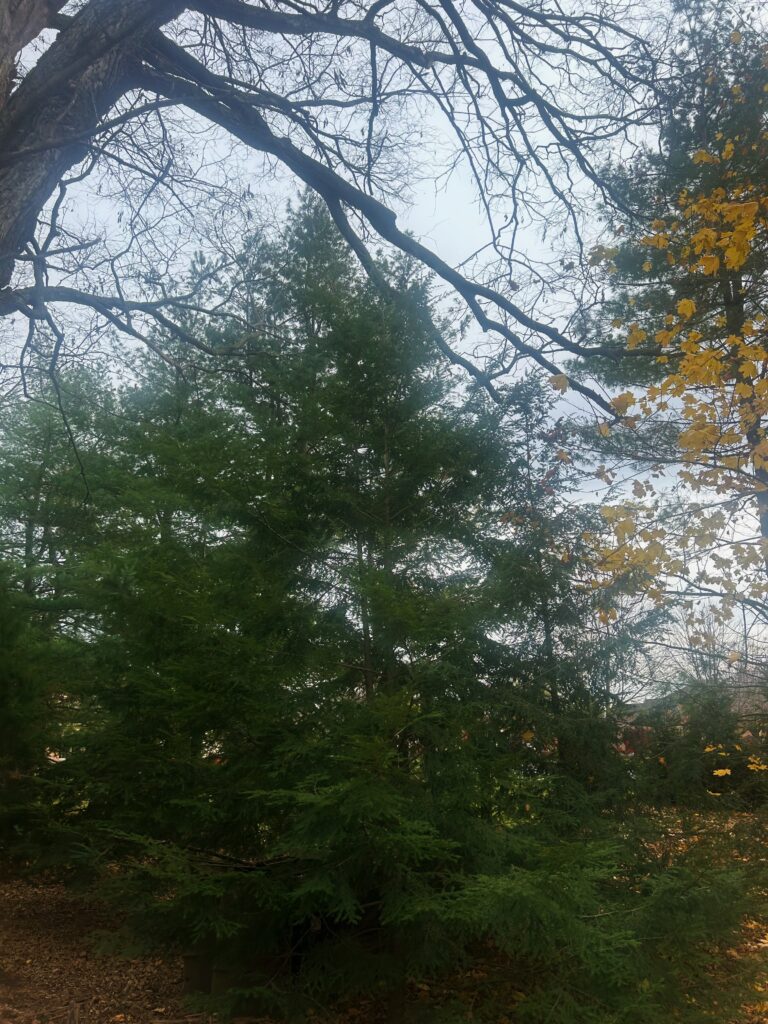

To the left of our phenology spot is a group of large Eastern white pines and Northern white cedars. These trees have become constants in our phenology spot, as they have towered over the area and stood tall throughout the course of the year, from the autumnal leaf changes to snow-covered branches to spring bud-breaking.

The Nature-Culture Connection:

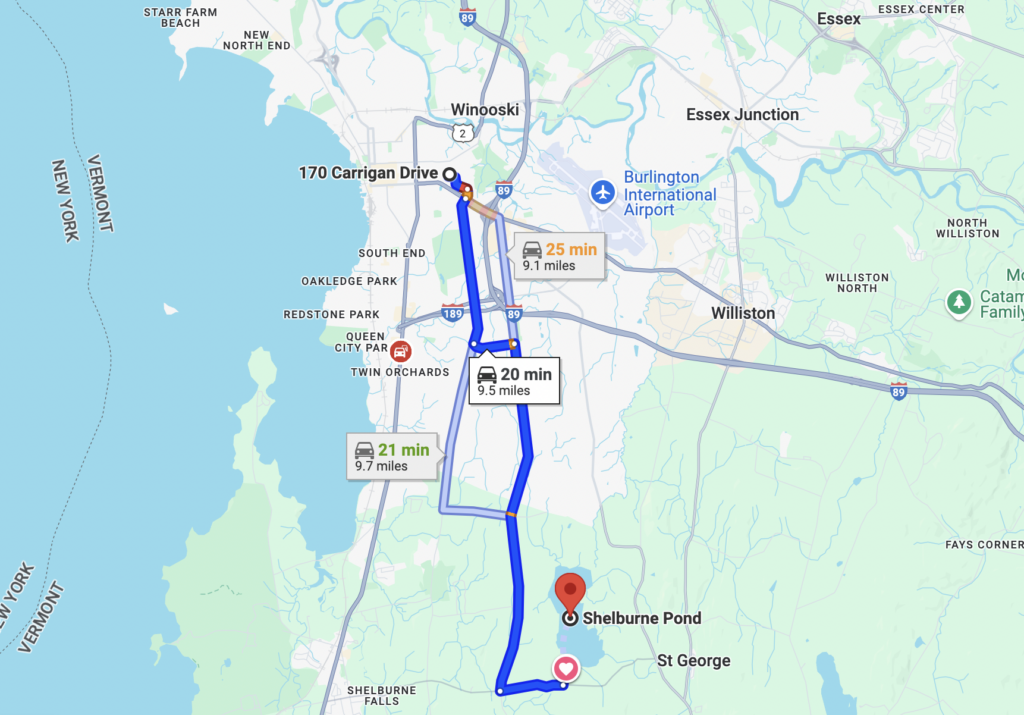

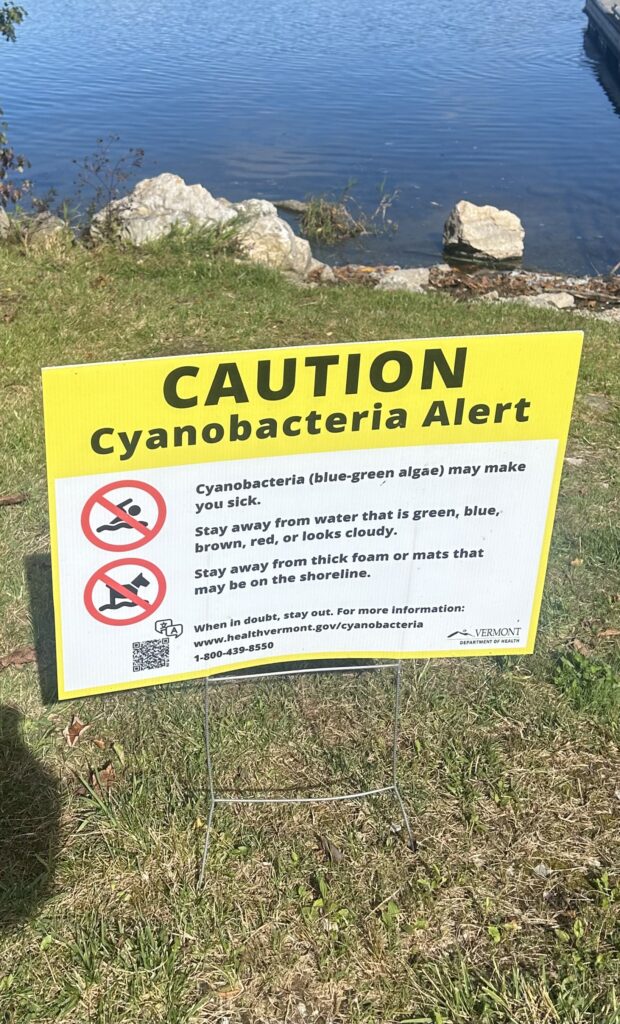

While we have taken a more ecological focus on our studies of the Shelburne Pond shoreline, this area is also a cultural and social recreation spot. This spot is somewhat far from any main road or development, but there are numerous public access points and hiking trails along our phenology spot. At its entrance, there is a large informational sign with maps, warnings, and general facts about the vegetation found at Shelburne Pond. Although we often did not see many hikers or boaters during our visits to Shelburne Pond, there was still a clear connection between Shelburne community members and this space. Shelburne Pond sits amongst large agricultural lands, farming operations, residential communities, and school zones. The pond’s beautiful view of the mountainous landscape, easy water access, and extensive trails make this spot more than just a great space to study phenology. I hope that the community members and visitors to this pond take the time to realize just how special these ecological communities and natural systems are, and find the same connection and sense of place to this pond as I have found over the past few months. In the future, I think it would be amazing to see Shelburne Pond become a stronger and more popular community space and research area while also working to conserve the habitats, wildlife, and views that can be found here, just 10 miles from downtown Burlington.

The Bigger Picture:

Thanks to our many visits and close interactions with the Shelburne Pond ecosystem, I would definitely consider myself a part of this place. I have changed a lot as a student, scientist, environmentalist, and individual during my first year of college, and I think it has been very fulfilling and special to observe another place that is undergoing many changes, too. My knowledge of this spot has grown exponentially, and I have become very familiar with each aspect of the community, from each oak tree down to the specific cattail. Through this intimacy and closeness with the land, I feel as though I am also a part of this ecological family. While at first I felt like I was more of a temporary visitor or onlooker of this spot, I now feel immense comfort and belonging here. Again, no matter what changes had been going on in my life at the time or the struggles I was encountering, this place remained constant for me. I could always rely on a trip to Shelburne Pond to remind me that change is good and natural. As I continue my next 3 years at the University of Vermont, I hope to continue returning to this spot to keep growing my relationship with this ecosystem and remind myself of my purpose and place here in Vermont as a Rubenstein student.