Islam in West Africa

Conceptions of Female Ritual Restrictions Among the Hausa and Tuareg

Introduction

The impact Islam has on women’s rights has been an area of debate in recent years. While some scholars consider Islam a religion for men with “an institutionalized mistrust of women” that views the female as “potentially dangerous and a source of disorder,” others contend that Islam has “given women many rights in the economic and political spheres” and the perception that Islam oppresses women is due to “patriarchal interpretations of the sacred texts, not…the texts themselves” (Coulon 117; Bop 1101). Indeed, Robinson rejects the notion that Islam is “misogynous” or “women-hating”; he writes that “Muhammad, the Quran, and the Sharia show great concern about the welfare of women,” and as a result Islam “represented a considerable improvement over conditions in Bedouin and Meccan society”—however, he concedes that “the institutions and practice have been dominated by men and have reinforced the patriarchal dimensions of society” (20-21).

One way in which some critics claim that Islam reinforces an Islamic patriarchal model is through ritual restrictions applied to women. Such restrictions are often centered around female sexuality, which has led some scholars to conclude that these restrictions are in place so men can control what they perceive to be women’s dangerous and potentially polluting sexual nature (Rasmussen, “Lack of Prayer” 751). While this assertion may be true, male intentionality is not the only factor that needs to be considered: more importantly, we must consider the female responses to ritual restrictions as well as the specific cultural values that function outside of Islam to reinforce such restrictions.

This essay will expand the debate by examining gender ideology in West Africa through the lens of two case studies: the first will focus on the practice of seclusion, or purdah, among the Hausa in Nigeria and Niger, and the second will look at menstrual taboos among the Tuareg tribes of the Maghreb. Using ethnographic research from these two groups, this paper will show that Islam can have many different and complex implications for the lives of women, and that generally it would be an oversimplification to just claim that Islam is either good for women or bad for women. We will see that ritual restrictions can be limiting, but that, in certain cultural contexts, they can also be a source of feminine power.

Background: Islam in North and West Africa

The spread of Islam into North and West Africa can be traced back to two main phenomena: trade and conquest. It appears that the first contact most West Africans had with Islam was around the middle of the seventh century CE, when Muslim traders “began to work [their] way across the trans-Saharan trade routes from North to West Africa” (Clarke 8). The exchange of goods indirectly functioned to spread Islam, because adherence to sharia law fostered “mutual trust among merchants in the long-distance trade,” so it was in traders’ best interests to convert to the new religion (Levtzion 3). As a result, many North Africans involved in the Trans-Saharan trade converted to Islam, and even those that did not were increasingly exposed to it. Such exposure also came in the form of warfare and conquest. After defeating Byzantine Imperial forces “in the middle of the seventh century, the Arabs gained control over coastal North Africa” but “failed to impose their authority over the Berber tribes of the interior” (Levtzion 2). Later, large swaths of this land would fall under the rule of successive Islamic dynasties. It is important to recognize that merchants and warriors brought with them several different types of Islam—Sufi, Sunni, Shi’a, Kharijite—and customs from these branches intermingled with local tradition to varying extents depending on the particular group.

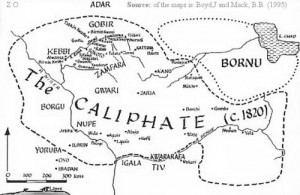

The Hausa, one of the largest ethnic groups in West Africa, span a large portion of the Sahel and can be found in many countries in the region. For the Hausa of Northern Nigeria and Southern Niger, Islam was the religion of elites from about the 15th through the 19th century (Henquinet 59). Pre-Islamic religions coexisted with Islam

until the beginning of 19th century when Usman Dan Fodio led a series of jihads and ultimately established the Sokoto Caliphate, an Islamic state that existed in Northern Nigeria until colonization by the British in 1903. Although British colonial entities swept away the Sokoto Caliphate and established their own government, they “viewed the indigenous Northern Nigerian establishment, including its religious institutions and judicial systems, as legitimate” (Miles 54). The British saw the institutions set up by the Islamic state, with power placed largely in the hands of male authorities, as conducive to their policy of indirect rule. Niger, however, had a different experience under the colonial yoke of the French. The French strategy of direct rule was more aggressive in dismantling African power structures. Islam was looked at unfavorably by the French because, as Miles puts it, “[they] distrusted any religious interference in colonial governance” (54). French policies of secularization led to an effort to dismantle previously existing institutions of power and establish secular rule in their colonies.

Among the Tuareg tribes, Islam was greeted with mixed reactions. The Tuareg “are a very diverse group of people,” composed of many different tribes with various reactions to Islam (Clarke 54). Keenan notes that Quranic influences (especially its inheritance rules) were seen by some as “a threat to the political and physical strength of the matrilineage,” but to other groups Islamic practices were actually adopted more “as a matter of political expediency than religious conviction” (Keenan 337). As with other Berber tribes, Islam did not replace—but was rather added to—existing social and spiritual customs. Additionally, “because of their many years of isolation, the Tuareg have been able to maintain customs and practices of their nomadic ancestors” (Standifer 53). Such practices included the importance of the matriliny, which influenced the freedom with which Tuareg women conducted their lives; many an Arab Muslim traveler criticized the Tuareg for “not properly restricting women” (Rasmussen, “Politics of Aging” 4), and indeed “the phenomenon of a matriarchal, matrilineal, or matrifocal-type of kinship system forcibly struck Arab Muslims when they first mixed with the Tuareg” (Norris 14). Be that as it may, the Tuareg largely converted to Islam, although for the most part they did not adhere to a strict Islamic orthodoxy, but instead adopted some aspects while discarding others.

Building off of this background history, this essay will now begin to look at the specific changes conversion to Islam had on Hausa and Tuareg society, focusing mainly on how Islamic conceptions of proper gender roles were adapted to traditional, pre-Islamic conceptions. Indeed, one would be remiss to overlook the effect that Islam has had on traditional gender roles in both the Hausa and Tuareg societies. A better understanding of this question can be gained by examining certain ritual practices and restrictions. For both groups, Islam has created new tensions in existing gender relationships, but to varying extents.

Case One: Purdah and the Hausa

In the case of the Hausa, the practice of seclusion is a development that has redefined expectations of both women and men in Northern Nigeria and Southern Niger. Seclusion, or purdah, can be found in numerous societies across West and North Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia, though “full purdah” is found more generally in urban contexts (Pastner 409). In Northern Nigeria and Southern Niger, purdah was practiced exclusively by elites until the establishment of the Sokoto caliphate in the mid 19th century.

Purdah among Muslim Hausa women begins when a woman is married and usually ends when she has passed through menopause. In Hausa society, marriage can start between the ages of 12-15. Women in purdah are not allowed outside in daylight and are not allowed to leave their husband’s compound without being veiled. They generally require their husband’s permission to visit other compounds, usually at night, and are held entirely accountable for their whereabouts. Women are forbidden from working in agriculture while in purdah, though there are exceptions; instead, they are expected to devote their energy to maintaining their homes for their husbands.

Though these conditions may be interpreted as harsh by some, they are seen as a privilege by others. According to Cooper, in Niger purdah is seen as an expression of a local “understanding of prosperity, leisure, and rank that is little informed by religion” (77). For women, these arrangements are preferable to the sometimes burdensome labor required in planting, harvesting, retrieving water, etc. For men, who are bound by the Quran to provide food and shelter for their wives, keeping their wife in seclusion signifies that they are strong, prosperous husbands who are capable of providing for their family, which increases both their status and respect. However, it can be difficult for a man to provide abundant resources for his family without the help of his wife. Many men are forced to leave their homes to look for work, often migrating for weeks or months at a time. Even in these instances, purdah is maintained in order to signal piety and prosperity, even if it doesn’t actually afford these rewards (Henquinet 69).

Purdah represents more than just leisure time for Hausa women. Many utilize their free time to devote resources towards personal crafts and services that help to earn additional income of their own. Hausa women have long been involved in trade, dating back to pre-Islamic periods. This tradition is maintained within seclusion through cloth-making and preparing meals for other families. However, because women are physically constrained to their households, they often use children to “hawk for their mothers,” running goods and products created by their mother to markets and private households (Callaway 440). In order to devote full attention to their household industries, many women will forgo making meals for their families, either by buying prepared meals, or in some cases a “husband will actually buy prepared food from his wife for his meals” (406 VerEecke).

There are, without a doubt, a number of negative impacts from this system. L. Lewis Wall points to a study which shows that an overwhelming majority of maternal deaths in Northern Nigeria occur among Hausa Muslim women who too often give birth at an exceedingly young age. Girls, sometimes as early as 10 years old, are pressured to marry and give birth when they are too young to physically do so. This is reinforced because “girls who are not married while in secondary school are viewed with suspicion” (Callaway 438). Early marriage leads to a lack of education, which is often so crucial for preventing early pregnancies (Wall 346).

Language is another important factor in enforcing ideas around marriage and seclusion. Cooper points out that “adulthood and marriage are linked” within the language of the Hausa (856). Women who are unmarried are sometimes referred to–especially by males–as karuwai, essentially equating them to a courtesan (Cooper 857). This kind of language can make unmarried women feel inferior and can reinforce the notion that they must marry in order to gain social stature. Associations between women and prostitutes date back to the beginning of the century. Steven Pierce argues that the beginning of this kind of language can be traced to a decree by the Emir of Kano in March of 1923. He was trying to prohibit women from inheriting land from their dead relatives on the grounds that “autonomous women were perceived as part of a problematic demimonde” (Pierce 469). What the emir saw as especially reminiscent of prostitution was the process of courtship among independent women. Women usually received multiple gifts from suitors that conveyed their interest in marriage. However, marriage was not a guaranteed result of this process. The fear was that independent women would abuse this system and gain advantage from free gifts (Pierce 471). Additionally, “adult female respectability is strongly correlated with marriage and seclusion, and this also correlates with men’s much greater ability to make a living” (Pierce 482). The emir’s association of the independent woman with prostitution has ultimately contributed to a severe stigmatization of unmarried women in Hausa society. Renee Pittin summed up this problem in another way:

In Hausa society, with its tradition of seclusion and strict social control, women are defined by their residence. Migration [to cities] by young women on their own is often seen as tantamount to prostitution, and prostitution is, initially, proved through migration. Hausa women are forced into a very narrow range of roles, limited still more by the women’s lack of education or other skills which would enable them to seek occupations in the formal sector of the economy (1312).

Thus, there are enormous social pressures on women to marry at a young age and practice seclusion.

In conclusion, although there are indeed a number of benefits women can gain from engaging in purdah such as free time to work on crafts and goods, relief from the hardship of agricultural labor, and an increase in social stature. However, an oppressive culture surrounds the practice, which can lead to high rates of maternal morbidity and social isolation. These are consequences which cannot not be ignored, and which stand a good chance of being addressed through increased education for women.

Case Two: Iban Emud and the Tuareg

As we will see, the case of the Tuareg is quite different than that of the Hausa despite their relatively close geographic proximity. In many ways, Tuareg society has resisted some of the aspects of a broader Islamic culture that are associated with the oppression of women, including practices such as seclusion. In a presentation to the Royal Geographic Society in Great Britain in 1926, Francis Rodd remarked that “among the Tuareg women are as free, if not freer, than in England… Their influence is very great” (32). While this is certainly subjective and open to debate, I do think there is a lot of truth to this observation. In Tuareg culture, female assertiveness is viewed as a “desirable feminine trait,” and women do not hesitate to “assert their right to a public presence and voice their opinions openly” (Worley). Women in Tuareg societies are not expected to wear a veil, they have a great deal of sexual freedom, retain large amounts of independence within marriage, and cannot be forced to marry a spouse against their will; additionally, wives are not secluded and it is easy for them to obtain divorces. Furthermore, women assume ownership over their own animals, care for the family herds, and “exert considerable influence over economic matters in general” (Nicolaisen II: 709, 712). Finally, women fulfill important roles as ritual healers and as mothers, which is, “according to both men and women,” one of the most valued roles in Tuareg society (Worley). In general, it is accurate to say that Tuareg women have a very visible public presence and are important members of the tribe due to their role in preserving the matriliny. However, while they do enjoy relative freedom and autonomy, ritual restrictions exist for Tuareg women during menstruation. What I hope to convey is that while menstrual taboos are associated with Islamic concerns surrounding impurity, in the Tuareg context the practice has less to do with Islamic concerns and more to do with Tuareg cultural values of modesty and reserve.

First, it will be helpful to have a brief discussion about perceptions surrounding menstrual taboos. Menstrual taboos do not only exist in Islam, but are present in many cultures and religions across the globe, including (but certainly not limited to) Judaism, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Christianity (see Guterman’s “Menstrual Taboos Among Major Religions” for further explication). Indeed, this “ordinary biological event has been subject to extraordinary symbolic elaboration in a wide variety of cultures,” the likes of which have led many anthropologists to view such taboos “as evidence of primitive irrationality and of the supposed universal dominance of men over women in society” (Buckley and Gottlieb 3). However, a different and perhaps more pertinent interpretation in the Tuareg context is that “menstrual customs, rather than subordinating women to men fearful of them, provide women with means of ensuring their own autonomy, influence, and social control” (Buckley and Gottlieb 7). Some scholars have even gone so far as to posit that restrictions surrounding women can be “enabling rather than constraining, especially when they are viewed in conjunction with other restrictions, including those that apply to men” (Rasmussen, “Lack of Prayer” 751). In order to illustrate this, we will take a closer look at ritual restrictions surrounding menstruation in Tuareg tribes.

In Tamacheq, the language of the Tuareg, the term for menstruation is “iban emud,” which literally translated means “lack of prayer” (Rasmussen, “Lack of Prayer” 751). While this references prayer restrictions for women during menses, it only tells half the story: menstruation is both “a prerequisite, just as much a limitation, to participating in Islamic observances” (Rasmussen, “Politics of Aging” 42). Menstruating women are not allowed to harvest crops, drink the milk of animals that have young, touch leather water containers used by men, pray or fast during Ramadan, or touch men’s swords and religious amulets. At the same time, menstruation is a rite of passage for women signifying when they come of child-bearing age, after which they are considered adults and begin to fast during Ramadan and participate in other rituals intended for adults only. Similarly, menstruation is associated with fertility, and is thus positively valued. Rasmussen is careful to point out that “ritual restrictions often surround figures of high status and authority,” and those surrounding menstruation “constitute efforts to control descent and protect the statuses of both men and women through a fusion of economics, descent, marriage, and household ties” (“Lack of Prayer” 755). Thus, restrictions during menstruation “emerge as part of general notions of dignity, reserve, and modesty among both men and women,” general notions that for women tend to focus on reproductive processes and for men focus on their face and mouth (Rasmussen, “Lack of Prayer” 759). Laxness in observance “results in a diminishing of self-respect, which, in the Tuareg view, implies not freedom but servitude”; similarly, the “dropping of restrictions implies actively polluting self and others” in the sense that doing so subjects one to harmful external influences that could negatively affect the entire community (Rasmussen, “Lack of Prayer” 755, 757). The Tuareg believe that bodily fluids of all kinds have the potential to carry danger, so rather than singling out women for menstruating, these ritual restrictions serve to protect women from harm at a time in which they are more susceptible to negative outside influences.

Thus, ritual restrictions among the Tuareg exist as an effort in “self-preservation in the face of competing forces, but these forces do not emanate from female biology alone” (Rasmussen, “Lack of Prayer” 766). Such restrictions, for men and for women, have more to do with the fragility of the matriliny than notions of impurity. Rather than hold women back, they function to protect both men and women at times when they are particularly vulnerable to harmful forces.

In addressing this paper’s broader theme of the impact that Islam has had on Tuareg women, the results are suggestive but not conclusive. The biggest obstacle to making a more definitive claim has been the lack of reliable sources describing Tuareg customs prior to the arrival of Islam. Clearly, one cannot say much about how Islam has impacted Tuareg women with a fragmented basis of comparison; at the same time, several sources claim that the Tuareg have mostly retained their pre-Islamic customs rather than adopt Islamic ways en masse. This could perhaps explain why in many ways Tuareg women enjoy much more social visibility, freedom, and mobility than do women in other predominantly Islamic societies. This suggests that although the Tuareg have accepted Islam, they have rejected the traditional gender roles associated with it. Therefore, while it is hard to make a definitive claim without knowing more about Tuareg women in pre-Islamic times, the evidence that is available implies that Islam has not had a negative impact on women’s lives, but has been adopted in such a way that has allowed the Tuareg to accept aspects of the religion while rejecting those that contradict their cultural values. Moreover, one must be careful to remember that there is not one monolithic “Islam,” but more accurately many different iterations of “Islam”; therefore, while there may be some forms that oppress women, as the Tuareg case proves there are also forms that do not.

Conclusions

Whether one understands Islam to have a positive or negative impact on the rights of women, it is clear that Islamic practice can be a significant force of cultural change. While at first glance it may seem like ritual restrictions such as seclusion and menstrual taboos only function to control women and subordinate them to men, there are ways in which women draw power and importance from these practices. There are several negative aspects of purdah, yet it has also been interpreted by Hausa women as a symbol of their family’s prosperity and an opportunity for them to enjoy leisure time and produce goods, which in turn affords them significant economic power. Their power can only increase as women gain more access to education and medical resources. Similarly, restrictions for menstruating Tuareg women may seem limiting, but menstruation is a rite of passage that is associated with fertility and the ability to become a mother, which is a highly valued status; in fact, restrictions exist for men as well, and for both genders such practices are more closely associated with preserving the matriliny and traditional Tuareg values than Islam. The negative aspects should not be downplayed—they should be identified and addressed; yet at the same time, it is important to recognize that women’s responses to such restrictions can lead to positive outcomes as well.

Notes on The Sources

The types of the research this paper has drawn on to examine the relationship between Islam and women in West Africa vary. Information about the Tuareg largely drew upon ethnographic research conducted within the last twenty years, although some of the research was a bit older. While there was certainly plenty to work with, the most recent ethnographic studies were performed by the same few researchers. Needless to say, research in this area would greatly benefit from the contributions of a larger, more diverse group of scholars as well as greater access to pre-Islamic Tuareg history.

Research on the Hausa was obtained primarily through ethnographic surveys and anthropological research in Niger and Nigeria. VerEecke, Henquinet, Cooper, and Callaway are all respected anthropologists with years of experience working in the region. There is also historical analysis by Cooper and Pierce, as well as a paper by Wall which draws its data primarily from the World Health Organization. Though these sources provide a broad view of this complex topic, the list of material lacks any book length analyses. This might prevent a more in depth and detailed examination of the topic.

Quick Reference Guide: Gender Role Comparison Between the Hausa and Tuareg

|

Gender Ideology among Muslim Hausa and Tuareg Women |

Hausa |

Tuareg |

|

Expected Social Behavior |

Women are expected to be submissive and defer to the judgement of their male superiors. When married, they must be veiled in public and are generally kept in seclusion. |

Women can be assertive and vocalize their opinions in a public manner. They have relative independence within marriage and are not expected to veil themselves. |

|

Economic Productivity |

Women in seclusion are expected to refrain from working in agriculture but are able to earn their own private income through trade in goods and services delivered to their clients through their children |

Women enjoy economic independence within their marriage and work in agriculture to bring income into their household. |

|

Ritual Restrictions |

Muslim Hausa practice seclusion, known as purdah, which confines a woman to her husband’s household for her childbearing years in marriage. She may leave the compound under the veil and accompanied by children. |

Menstruating Tuareg Muslim women are not allowed to harvest crops, drink the milk of animals that have young, touch leather water containers used by men, pray or fast during Ramadan, or touch men’s swords and religious amulets. |

Works Cited

Bop, C. “Roles and the Position of Women in Sufi Brotherhoods in Senegal.” Journal of the American Academy of Religion 73.4 (2005): 1099–1119.

Buckley, Thomas, and Alma Gottlieb, eds. Blood Magic: The Anthropology of Menstruation. Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press, 1988. Print.

Callaway, Barabara J. “Ambiguous Consequences of Socialization and Seclusion of Hausa Women,” The Journal of Modern African Studies, Vol. 22, No. 3 (Sept. 1984), pp. 429-450

Clarke, Peter B. West Africa and Islam. London, UK: Edward Arnold Publishers, 1982. Print.

Cooper, Barbara M. “The Politics of Difference and Women’s Associations in Niger: Of “Prostitutes,” the Public, and Politics,” Signs, Col. 20, No. 4, Postcolonial, Emergent, and Indigenous Feminisims, (Summer, 1995), pp 851-882

Coulon, C. “Women, Islam, and Baraka.” Donal Cruise O’Brien & Christian Coulon, eds. Charisma and Brotherhood in African Islam. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1988. 113–135.

Henquinet, Kari Bergstrom. “The Rise of Wife Seclusion in Rural South Central Niger ,“ Ethnology, Vol. 46, No. 1 (Winter 2007), pp. 57-80

Keenan, Jeremy. “Power And Wealth Are Cousins: Descent, Class And Marital Strategies Among The Kel Ahaggar (Tuareg-Sahara) Part II.” Africa (Edinburgh University Press) 47.4 (1977): 333.

Levtzion, Nehemia, and Randall L. Pouwels, eds. The History of Islam in Africa. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2000. Print.

L. Lewis Wall, “Dead Mothers and Injured Wives: The Social Context of Maternal Morbidity and Mortality,” Studies in Family Planning, Vol. 29, No. 4 (Dec. 1998), pp. 341-359

Miles, William F.S. “Shari’a as De-Africanization: Evidence from Hausaland,” Africa Today, Vol. 50, No. 1, Spring 2003, pp. 51-75

Nicolaisen, Ida, ed. The Pastoral Tuareg: Ecology, Culture, and Society, Volume Two. New York, NY: Thames and Hudson Inc., 1997.

Norris, H.T. The Tuaregs: Their Islamic Legacy and Its Diffusion in the Sahel. Wiltshire, England: Aris & Phillips Ltd., 1975.

Pastner, Carroll McC. “Accommodations to Purdah: The Female Perspective”, in Journal of Marriage and Family, Vol. 36, No. 2 (May, 1974) pp. 408-414

Pierce, Steven. “ ‘Farmers and Prostitutes’: Twentieth-Century Problems of Female Inheritance in Kano, Emirate, Nigeria,” The Journal of African History, Vol. 44, No. 3 (2003), pp. 463-486

Pittin, Renee. “Migration of Women in Nigeria: The Hausa Case,” International Migration Review, Vol. 18, No. 4, Special Issue: Women in Migration (Winter, 1984), pp 1293-1314

Rasmussen, Susan J. “Lack of Prayer: Ritual Restrictions, Social Experience, and the Anthropology of Menstruation Among the Tuareg.” American Ethnologist 18.4 (1991): 751–769.

Rasmussen, Susan J. The Poetics and Politics of Tuareg Aging. Dekalb, IL: Northern Illinois University Press, 1997.

Robinson, David. Muslim Societies in African History. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2004. Print.

Rodd, Francis. “The Origin of the Tuareg.” The Geographical Journal 67.1 (1926): 27–47.

Standifer, James. “The Tuareg: Their Music and Dances.” The Black Perspective in Music 16.1 (1988): 45–62.

Worley, Barbara A. “Where All the Women Are Strong.” Natural History 101.11 (1992): 54.