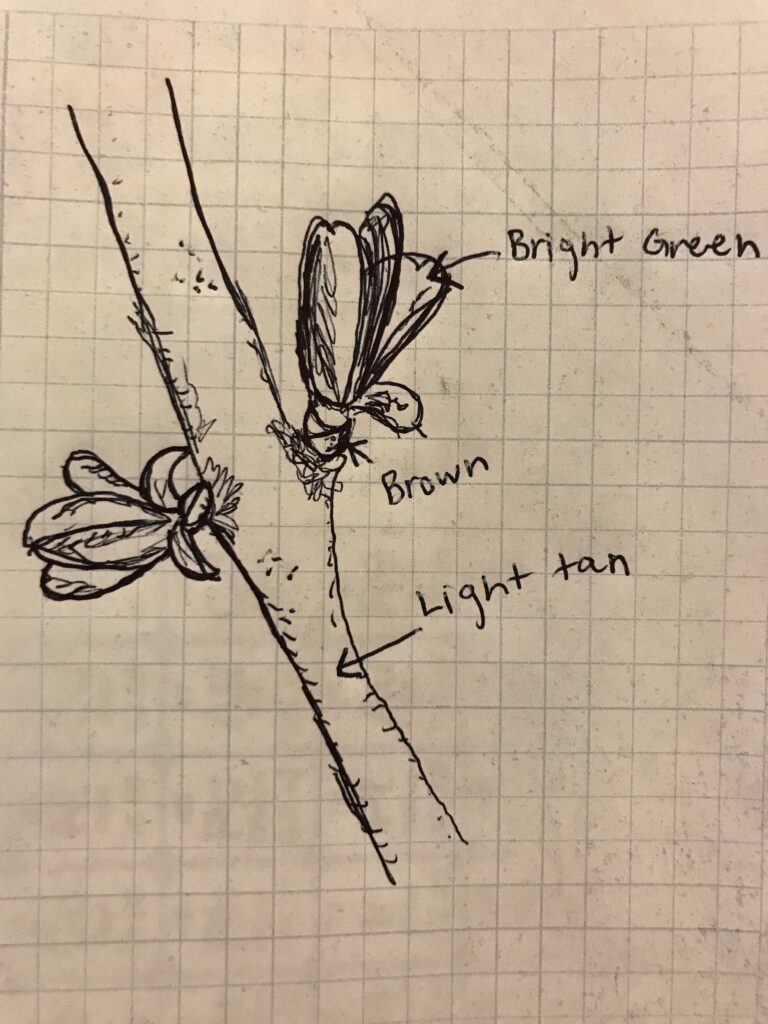

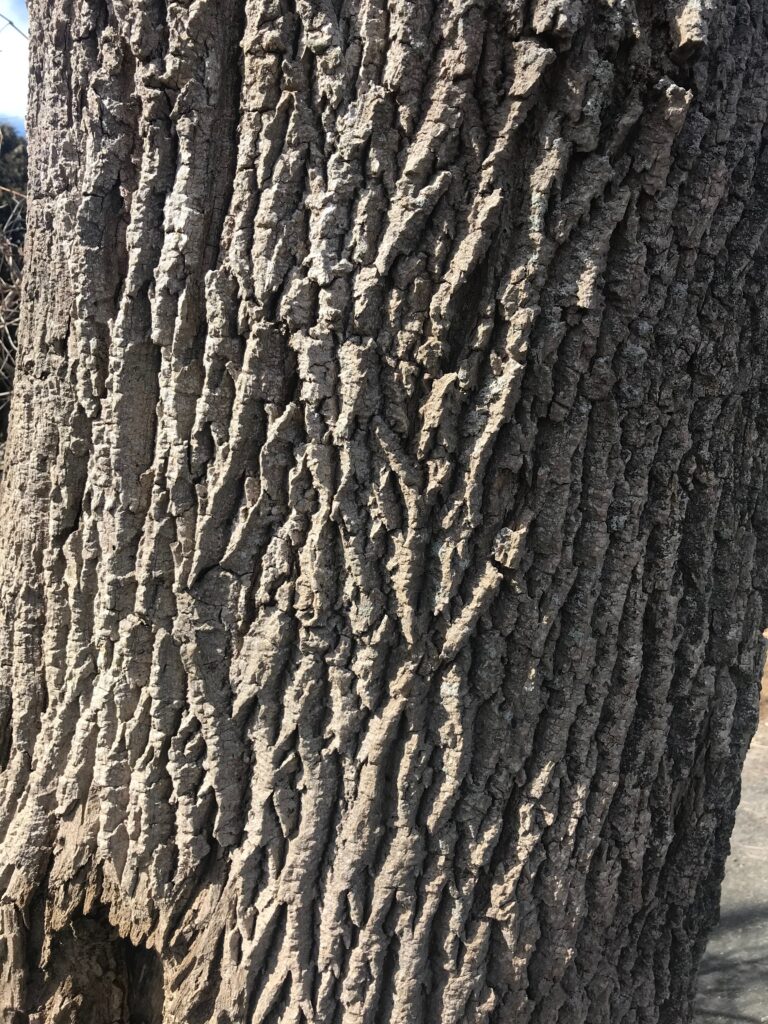

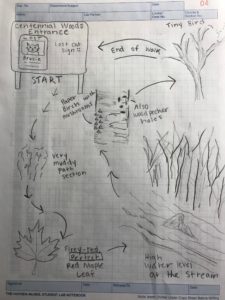

Today I made one last visit to my phenology. It was around 50 degrees and partially sunny. Already I noticed slight change from my last visit- the fiddleheads arrived. Reflecting all the way back to my first visit to the site in September, I remember how heavily vegetated with ferns the understory becomes later in the season.

Additionally, the bright morning brought about lots of life. I heard several bird species chirping and even saw a chipmunk. Everything was lively. Having visited this site time and time again throughout the semester, I have grown a connection to the area and loved to witness its phenological changes. While understanding that the ecosystem does not need me to be whole, I still consider myself part of it. I am a piece of the ecosystem the same way every other plant or animal is. My visits and connection to the site has allowed me to value the site in a new way beyond just the its traditional ecological values. I think it is important for people to draw these connections to the land and feel a sense of place as it benefits both the land and individual.

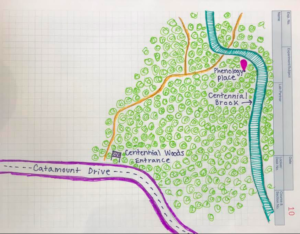

Nature and culture have a strong history, intertwining at my spot. The location was initially Abenaki land used to support a naturalist, complex system of people. Over the years as culture changed, so did the land. In the time of peak land clearance, the forest disappeared, hurting biodiversity. Still, the resilience the land allowed for the forest return. As the forest developed so did human culture. Today the individual paths of development of the forest and myself have lead us to a place where connection was created.