I have long wished for information on a subject which at first blush you may not deem worthy of notice…

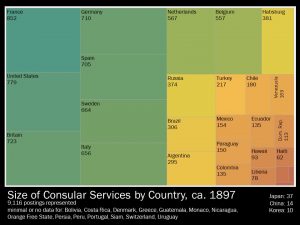

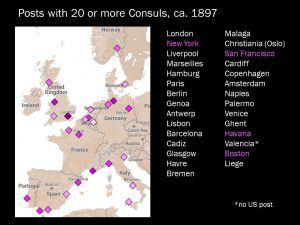

Theodore Sternberg of Ellsworth, Kansas divulged his enduring passion in a letter to Secretary of State Walter Gresham in May, 1893: “I should much like to see Consular reports … regarding the several breeds of fowls native to the [world’s] countries, their habits and special tendencies.” Secretary Gresham and his DOS colleagues apparently concurred with Sternberg that “out of such information may come some thing which may be of economic value to our own people,” but they weren’t sure at that point what specific information Sternberg wanted. They invited him to submit a list of questions and, upon receipt, issued a circular instruction to the entire service, calling on them to provide local data in response to Sternberg’s ten questions. At the time, the service consisted of approximately eight hundred posts across the world. Consular officials from Spain to Saigon sent back reports—my favorite titled “Chickens of Egypt”—that addressed Sternberg’s questions about local varieties, including “pure races” and “fancy” fowls, as well as artificial incubation techniques and the methods by which Americans could import the birds.

This isn’t the only instance I’ve found of an individual’s request for information producing a massive, time-consuming response from the US Consular Service, but it is certainly my favorite so far, not least because the experience of looking through the responses at the US National Archives in College Park felt sort of like stepping into a Far Side cartoon. I haven’t yet looked for the final report, but I’m confident that it can’t be as cool as the raw materials in archives. Here are some of my favorites; click on the images to view larger versions. The best is, of course, at the end…

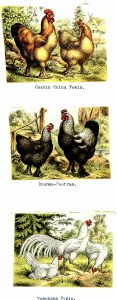

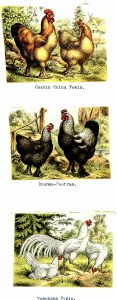

An assortment of color drawings — presumably not produced by a member of the consular staff — depicting some chicken breeds in Asia:

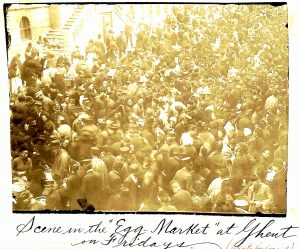

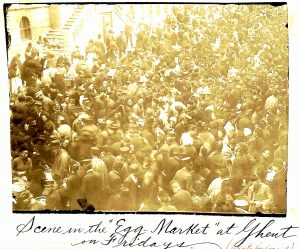

A consul’s photograph of the Egg Market at Ghent, in Belgium:

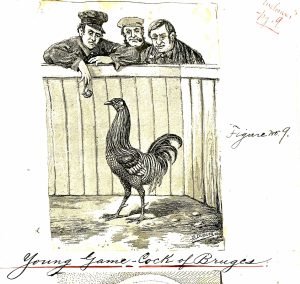

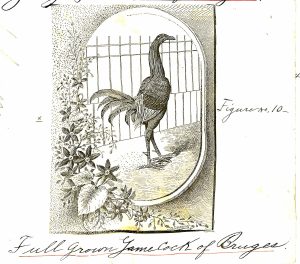

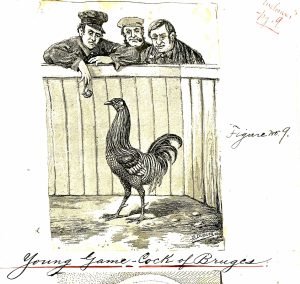

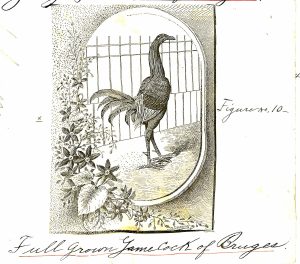

The Game-Cock of Bruges, pictured first in its — potentially delinquent — youth and then in a more domestic setting appropriate to full maturity:

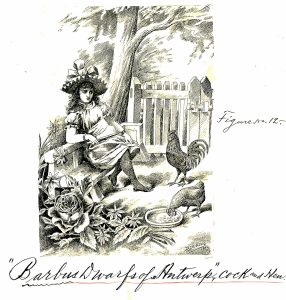

Belgium was (is?) definitely quite the place for poultry. One consul sent a translation of a newspaper article on “The Brussels Chicken,” and another provided this artistic rendering of a woman with examples of cock and hen “Barbus Dwarfs of Antwerp”:

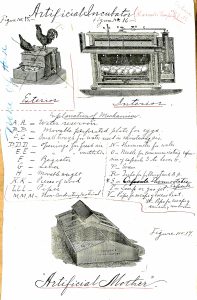

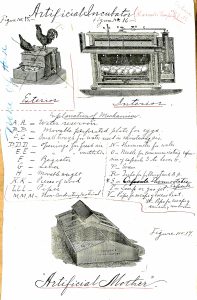

Apparently, the “Artificial Mother” and these other incubators didn’t make the department’s final report:

But the absolute best thing in the collection were these marvelous feathers. The consul at Brunswick, Germany provided them as “proof of light and dark buff spangled booted Bantams.” They’re held onto a card with sealing wax. I am so used to reading reports that provide tantalizing mention of enclosures that are no longer with the documents that I had no expectation at all of turning this report over to find an envelope with the promised feathers in it. But there it was! In all its feathery glory!

All of these items can be found in the US National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, Maryland, Record Group 59: General Records of the Department of State, Inventory 15, Entry 86: Miscellaneous Consular Trade Reports, Folder 1. Declassification via State Letter 1/11/72.