There is a certain conceptualization of the place of queer bodies in religious spaces in the Western imagination. Religion and queerness are often posited as existing in opposite realms, as if there are endless, inherent contradictions between individuals holding both identities in tandem. In the last several decades, queer religious actors have gained more visibility through news outlets and social media platforms, but this visibility is often limited to white middle-class Christians and Jews. There is still very little wiggle room in the Western imagination for Muslims to claim identities that are both religious and queer. This is due in part to the ways that Islam and Muslims are racialized.

Islam is often portrayed as inherently fanatical, homophobic, and patriarchal and that racialization is painted onto the bodies of queer Muslims. Queer Jews and Christians who have gained public acceptance have been able to do so because they fit into the Western national imagination of belonging. Even if they are not hetero-normative, they are imagined as white and not overly religious or practicing the “wrong” kind of religiosity. In contrast, queer Muslims are not given this kind of visibility or legitimacy because they are always imagined as people of color and practicing an irrational form of religion.

In addition to this racialization, the experiences of queer Muslims are erased in the West because Islam and queerness are considered to be mutually exclusive. The assumption of mutual exclusivity highlights how queerness is associated with the West and how Islam is associated with homophobia and the inability to accept queer public equality. This categorization further feeds the assumptions about Muslims as “other” in Western culture and their assumed inability to fit into the West’s values of democracy, secularism, and tolerance. (Rahman, 948).

While the predominant narrative in the West has been the message that Islam is homophobic, if we define Islam as what Muslims do and say that Islam is, this message is both upheld and demolished. Some Muslims argue that the Qur’an and hadiths condemn homosexuality while other Muslims argue that their faith is queer-affirming. Imam Daayie Abdullah, an openly gay black Imam in DC, believes that the prevalent view in mainstream Islamic discourse of homosexuality as a sin is rooted in particular interpretations and traditions, rather than scripture. “Many traditions are locked into a particular time, place, and culture, they’re not necessarily appropriate for us today or for people who will be worshipping in 50 years from now,” Abdullah said in an NBC news interview conducted in April 2019 on how queer Muslims reconcile their faith with their sexuality. Religion is not an unchanging, untouchable tangible “thing”. Islam is not inherently anything. Instead, it is the conglomeration of the different ways that Muslims have expressed themselves and practiced their religiosity throughout time.

Queer Muslims have always been a part of Islam because queer Muslims have always existed. This acknowledgement of existence does not erase all of the ways that queer Muslims have been marginalized in the West, both as racialized religious bodies and as individuals engaged in expressions of gender and sexuality that are deemed as non-normative. Because queer Muslims have always existed and because Islam is not a monolith, there have always been different ways that queer Muslims engage with their tradition, especially the elements of their tradition that are seen as inherently homophobic and transphobic.

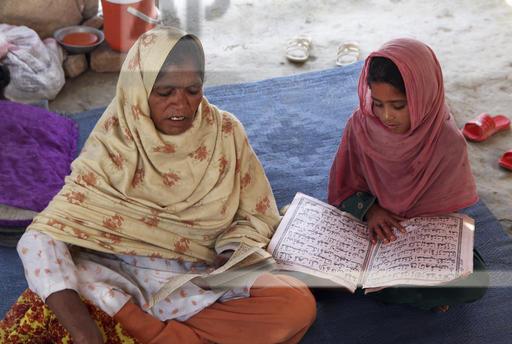

Many non-Muslim Westerners make the mistake of assuming that queer Muslims must leave Islam if they want to embrace their queer identity. While some queer Muslims might choose to leave their tradition all together, many remain engaged in their faith practice, pursue deeper knowledge about its practices and histories, reinterpret texts, and reframe rituals to comfortably accommodate their intersecting identities (Kugle, 53). One way that queer Muslim activists engage their faith practice in reclaiming their religious tradition is through turning to the Qur’an or hadiths for symbolic affirmation of their inherent worth and dignity (Kugle, 22).

Imam El-Farouk Khaki, founder of Toronto’s first LGBTQ+ friendly mosque, quoted chapter 39, verse 13 of the Quran when asked why he created the mosque. This verse “tells us that diversity and difference are part of God’s plan and should be celebrated. We are trying to live it,” he said (25). Many queer Muslims report feeling excluded, uncomfortable, and often unsafe in “traditional” Muslim spaces. In response to this feeling of a lack of belonging, queer Muslims have created LGBTQ+ friendly Muslim spaces such as mosques, queer Qur’an study groups, and community circles. Muhsin Hendricks, a queer South African Imam, started an organization in 1996 called Inner Circle that seeks to bring gay Muslim men into dialogue, provides spiritual and emotional guidance, and offers support for reconciling faith with sexual orientation and gender identities (Hendricks, 496). Reinterpreting and reframing scripture and creating new inclusive religious spaces are both ways that Islam can be “queered”. Queering Islam often looks like centering LGBTQ+ Muslim voices and perspectives and challenging heteronormative and authoritative discourses on Islam.

Even within LGBTQ+ spaces, queer Muslims are often still marginalized and rendered invisible. The LGBTQ+ community is often portrayed as a secular space. In media accounts, “religion often appears only as something that a person needs to leave behind in order to become liberated. There seems to be little or no space for faith as a positive force in a person’s life” (Khan, 21). Within these spaces, other religious identities, such as Christians and Jews, are often categorized as secular or at least as being the “right” kind of religious and are thus accepted.

Since Islam and Muslims are racialized, they are not awarded the same legitimacy and are often seen as being overly religious. As subjects who are marked as non-homonormative (as brown and religious bodies), queer Muslims are expected to engage in homonormative practices within these spaces to achieve this kind of legitimacy. In the words of Nayyeema, who identities as a Pakistani genderqueer feminist, to be accepted into LGBTQ+ American homonormative spaces, queer Muslims have to “do gay and be gay like you. I have to love (white) and be loved (white) like you.” (Khan, 22) In order for queer Muslims to fit into these predominantly white spaces, they are often encouraged to renounce certain parts of their identities.

Works Cited

Khan, Sasha. “Constructing the Queer Muslim: The Necropolitics of Racialization and Western Exceptionalism in the Lives of LGBTQ Muslims. Simmons College, 2017.

Kugle, Scott. Living Out Islam: Voices of Lesbian, Gay, and Transgender Muslims. New York University Press, 2014.

Hendricks, Muhsin and Krondorfer, Bjorn. “Diversity of Sexuality in Islam: Interview with Imam Muhsin Hendricks”. Cross Currents, vol 61, no. 4, 2001, pp. 496-501.

Rahman, Momim. “Queer as Intersectionality: Theorizing Gay Muslim Identities.”Sage Sociology, v 44, pp. 944–961, 2010.

Salter, Shala Khan. The Ottawa Capital Pride Parade’s LGBTQ Muslim Contingent and Allies. Ottawa, 2018.