Can you pinpoint the moments in history that make you who you are? The moments that have created your identity? For Muslims, as well as other religious communities in India such as Hindus and Sikhs, one of these defining and shaping moments is the Partition/Independence of India of 1947. It is a moment both definitional of, and resultant from, a first colonial, and then imperial, British imperial influence.

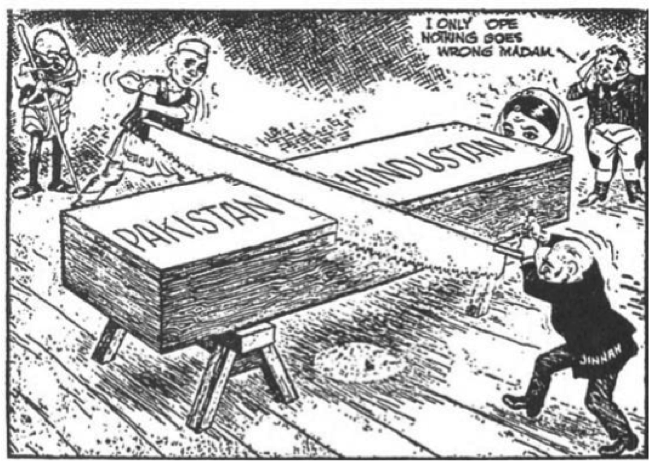

Nehru and Jinnah are depicted as sawing through Mother India, with Gandhi and the British as spectators.

It is too bold to suggest that the entirety of Muslim identities in South Asia changed with Partition. For this reason, I am specifically investigating Muhammad Ali Jinnah and the All-India Muslim league. Particularly, the imaginations of religious identities of the post-Partition/post-Independent Muslim community, as depicted in the cartoon, “Sawing Through a Woman”, displayed to the right. It was published in July 1947 just one month before Partition/Independence took place. Using this image, the question that I aim to investigate is: how did the imagination of the Partition/Independence of India, based on the political cartoon “Sawing Through a Woman”, differ from the reality of what Jinnah and the All-India Muslim League imagined for post-Partition/Independence Pakistani Muslims? Arguably, Jinnah and other Muslims alike imagined a different, more united and perhaps less violent, reality from what actually came to be. I am claiming that what was at stake here, was the identities of the millions of people who had to adjust to a new, and very different, geopolitical framework in light of Partition.

As a political cartoon, “Sawing through a woman” provides great insight into Partition/Independence imaginations. Jawaharlal Nehru, the man dressed predominantly in white, and Muhammad Ali Jinnah, dressed in all black, are depicted as sawing the box that contains the Bharat Mata or Mother India (better known as the embodied feminine, nationalistic, representation of India). Mohandas Gandhi and a British representative are depicted stereotypically, in the background.

In order to understand Partition/Independence, it is necessary to think about these political actors as well as the political spheres that set the stage. In short, by 1947, tensions are high between British imperial forces and the Indian people, and the British are looking to leave India quickly and quietly. At the same time, there is the major question in Indian politics of how to protect the Muslim minority (Metcalf, 207). Jinnah is among the first to suggest that Hindu and Muslim people should be politically separate. However, both Nehru and the Indian National Congress had a vision of sociocultural and industrial change with technology, education, and the eradication of caste (Naim, 150). They had two completely different visions. Additionally, if we pay attention to the British actor in the image, he speaks widely to tensions that were present in India, and the uncertainty that would come after Independence/Partition. As a result, Indians believed Partition/Independence was viewed as the only way to save the Mother from the damages that had been done in light of British colonization and imperial influence.

Thinking about this idea of the “Mother”, the only feminine body that you see is Mother India’s head on the side of the box that is labeled as Hindustan. She is central to the cartoon, just as she was central to Partition/Independence. Based on this depiction of the Mother, I think it can be said that identities, deconstructions, and formations in light of Partition/Independence, would occur not because of the event itself, but in the act of saving the Mother. I think that for Hindus, perhaps, this meant remaining by her side, and for Muslims, this meant leaving her so that they could see what they achieve without her; as they were now free from a political system and society where Muslims were not represented properly. In order to do so, Muslims would have to both embrace their identity as distinctive from Hindus, and perhaps pick and choose what to take or leave as a formerly Indian and newly Pakistani people. Therefore, the only way to save the Mother would be, to cut her in the process.

Thinking about Jinnah and what he imagined for the Pakistani community, it is essential to think about his Fourteen Points, an important idea that preceded his Two Nation Theory. When Jinnah thought of the idea of Pakistan he did so with the notion that it would be a place where Muslims would be united through society, culture, trade, and politics; despite the fact that the nation-state itself was divided geographically by India (Ahmed, 145). This idea was first laid out in March of 1940 during the All India Muslim League’s session in Lahore where Jinnah famously stated that Muslims and Hindus “were irreconcilably opposed monolithic religious communities.” At the end of the conference, the Lahore Resolution was established, which stated, “the areas in which the Muslims are numerically in majority as in the North-Western and North-Eastern zones of India should be grouped to constitute independent states in which the constituent units shall be autonomous and sovereign (Khan, 37).”

A depiction of India ( yellow) and Pakistan (green) after Partition. The orange represents borders of India and Pakistan that remain in flux.

Because these groupings lay in the northwest and northeast of India, realistically, the country was “sawed” into three segments. The political cartoon does not depict the topographic reality of what India and East and West Pakistan would look like after Partition/Independence. Rather, it imagines that Pakistan would be a whole country despite the landmass, that is India, between them. As far as political actors’ imaginations go, it would appear that the woman in the box could not avoid being harmed as she is sawed in half. But, as the famous trick goes, this is not the case and she goes unscathed.

However, the reality is that Partition/Independence was a violent event. In thinking about the ways in which Mother India was sawn in half in the cartoon, there is a violent element to the cartoon that asks, what does it mean to cut up your mother? In her book Goddess and the Nation: Mapping Mother India, Sumathi Ramaswamy questions the ways in which maps, as they are drawn and re-drawn, foster the sentiment of intimate belonging that is so crucial to the imagined community of the nation? And further, how does the citizen, who stands removed from the new territorial space, come to see it as his “homeland”, in which he belongs? And finally, how can the young citizen feel moved to give up his life for this map (Ramaswamy, 175)? Referencing partition, Ramaswamy attributes this to the idea of the geo-body of the nation and the ways in which it “pictorially converts the citizen-subject from being a detached observer of the carto-graphed image of India into its worshipful patriot, so that its territory is not just the lines and contours on a map but a mother and a motherland worth dying for (Ramaswamy, 176).” Perhaps, this is the very reason for the mass violence that erupted in light of Partition/Independence. And so, I am inclined to question the role of accompanying violence in shaping post-Partition/Independence identities.

Thinking about the mass violence that came with Partition/Independence’s call to deconstruct and recreate identities, it would be worthwhile to think about the creation of a nation-state, and independence from the British (as imperial oppressors) as apologetic. Throughout his piece Apologetic Modernity, Faisal Devji claims that there is intimacy between modernity and colonialism (Devji, 64). As a result, Partition/Independence is both the literal and figurative space where Muslims became their own historical actors with morals, ideas, etc. In the case of Partition/Independence, when the Mother was cut, they created their own modernity, and effectively, their own new identity, which was suddenly separate from Hindu Indians, but nonetheless, derived from some of that very same identity.

I have found that modernity for post-Partition/Independence Muslims came to be defined as the space around which contemporary understandings of what late-colonial Muslims thought Islam was, and its place in a new world. And so, in thinking about how Partition/Independence shaped the identities of the late-imperial era, it is important to think about both the intimate, and personal agencies that were involved; as well as the ways in which they were simultaneously in and out of control.

Bibliography

- Ahmed, Akbar S. Jinnah, Pakistan, and Islamic Identity: The Search for Saladin. Routledge, London (1997), 258pp.

- Devji, “Apologetic Modernity,” in Modern Intellectual History, 4, 1(2007), pp. 61-

- 76.Dhulipala, Venkat, Creating a New Medina: State Power, Islam, and the Quest for Pakistan in Late Colonial North India. New York: Cambridge University Press, (2015). 554 pp.

- Khan, Yasmin (2007). The Great Partition: The Making of India and Pakistan. Yale University Press.

- Metcalf Barbara D. and Metcalf, Thomas R., A Concise History of Modern India, third edition. Cambridge University Press (2012), pp 203-264.

- Naim, C.M., Iqbal, Jinnah, and Pakistan: The Vision and the Reality. Syracuse University Press (1979), pp. 150.

- Philips, C.H., The Partition of India: Policies and Perspectives 1935-147. George Allen&Unwin Ltd (1969), 553pp.

- Prasad, Bimal, Pathway to India’s Partition: the Foundations of Muslim Nationalism, vo1 1. Rajikamal Electric Press (1999), 319pp.

- Ramaswamy, Sumathi, The Goddess and The Nation: Mapping Mother India. Duke University Press: Durham and London (2010), 379 pp.

- Unknown Author “Sawing through a woman”, Pioneer July 8, 1947) image.

- “Partition of India 1947” image. Accessed November 02, 2015 at http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/modern/partition1947_01.shtml