Posted in Uncategorized | Tagged 5/4/19 | Leave a Comment »

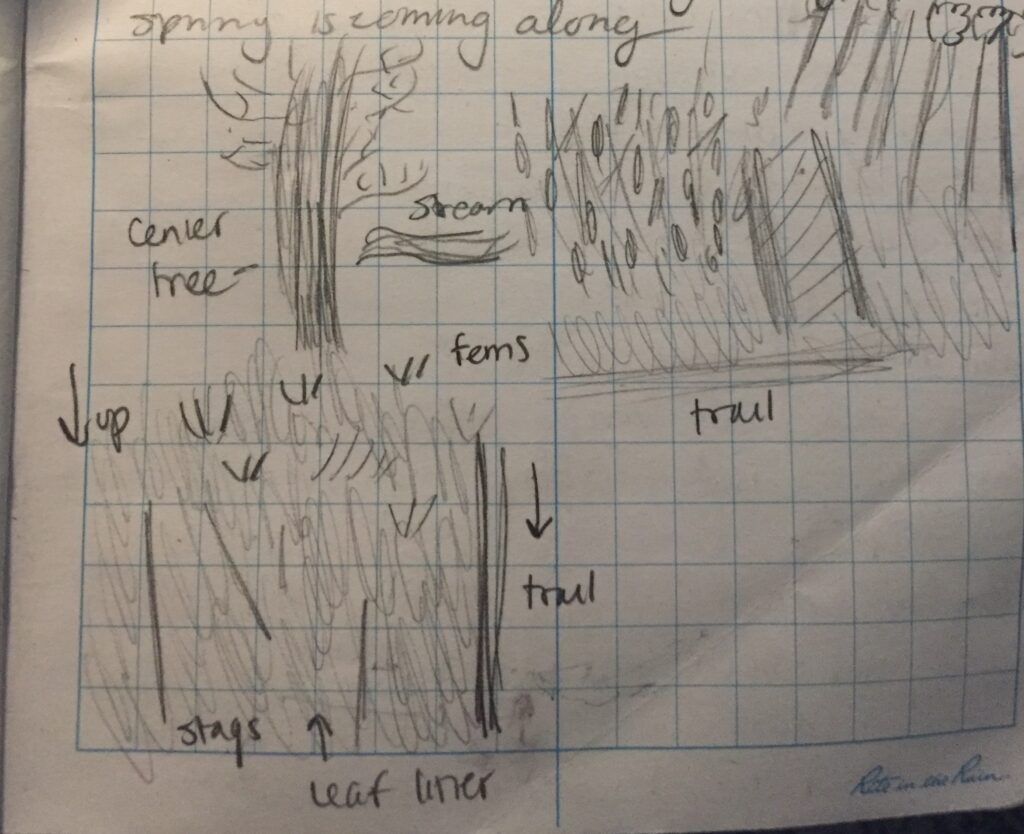

Spring is finally on its way, and I’m beginning to see the changes it brings in Centennial Woods. The ferns have started to pop up around the leaf litter. The rest of the forest floor is coated with dead leaves, twigs/branches, and mud. The soil seems to be eroding from recent flooding, and the mud was thick and heavy. I also was able to hear the downwards stream (Centennial Brook) from my site. I didn’t notice any budding, but younger Eastern Hemlocks seemed to be growing, filling out the rest of the landscape. I also noticed how active the birds were becoming in my site, as I heard Black Capped Chickadees and European Starlings.

Posted in 4/27/19 | Leave a Comment »

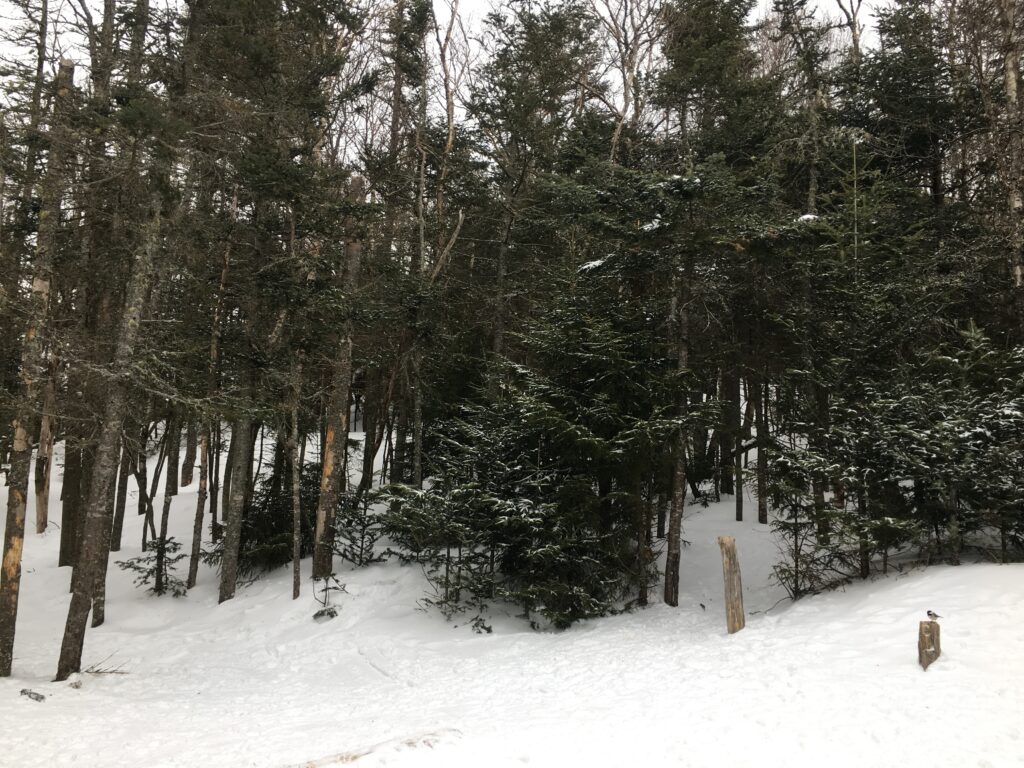

During spring break, my family and I went skiing at Loon Mountain in Lincoln, New Hampshire. While skiing, we stopped along the side of a trail to visit a bird sanctuary. Since we were at a high elevation, tree species I saw include Yellow Birch, Fraser Fir, and Balsam Fir. More shrubby coniferous trees were here, compared to my Burlington site that located at a lower elevation with less species diversity. While at the sanctuary, I saw (and held) Black-capped Chickadees and Red-breasted Nuthatches, both being small woodland birds. The latter species are interesting as they have the unique ability of climbing down trees head first. Black-capped Chickadees are adaptable, and can accommodate a mixed diet of seeds. The low clearings and availability of seeds creates a hotspot for birds like these, unlike my site in Vermont, where the Hemlocks grow too tall.

Posted in 3/18/19 | Leave a Comment »

The natural community of Centennial Woods can be classified as the Northern Hardwood Forest, and is located in the Champlain Valley. This forest is dominated by Yellow Birch, Sugar Maple, American Beech, Eastern White Pine, and Eastern Hemlock; which dominates my natural site. This is also the natural forest type below 2,500 feet in Vermont.

Recent Changes

As you can see from the content of this blog, there has been significant phenological changes here since the fall of last year. Recent changes include the increase of snags, which leads to an increase of branches scattering the forest floor. I may have spotted some deer tracks during my last visit, however, there is so much foot traffic on the trail that finding clear tracks is challenging. There was less snow cover, leaving the ground with a layer of ice, which could affect the substrate when it melts, and wildlife habitat, especially because my site is located around a steep incline (difficult to hunt, find shelter).

Changes Since last Year

Since the fall, the biggest difference is the prevalence of Eastern Hemlock. They’ve always been here, but absence of hardwoods (leaves, noticeable growth) gives the Hemlock dominance. The ferns have died/have become covered in snow, which changes the appearance of the landscape. The land seems barren and deserted, compared to its lush state of last year. Lack of birds and noticeable wildlife makes the area unusually quiet, and its presence over the sloping hill is emphasized. I also hadn’t considered the impacts of the adjacent clearing next to my site until my last visit. It was cleared to put up power lines, and this disturbance could account for the lack of wildlife so close to the site.

Posted in 3/8/19 | Leave a Comment »

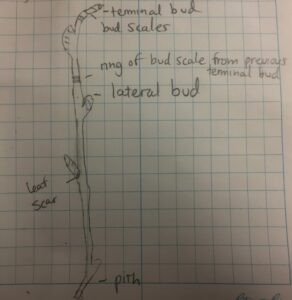

Coming back from break, I noticed differences at my site in Centennial Woods. The dying ferns that covered the forest floor (especially sloping down) were completely covered, as the ferns were less than a foot tall. Since the Eastern Hemlocks at the site are the only trees left with piny leaves, they stood out the most. I was only able to find the twig of possibly a small American Beech (sapling), although I remember identifying Red Maples in the fall. I also noticed more stags than I remember from before, all picked over by pileated woodpeckers. The snowfall was also lighter in my site, as the E. Hemlocks provided a good covering. The path that dissects my area is well used, so I saw many canine tracks. In addition, I saw deer and possibly weasel tracks that led up to an intricate group of holes which could lead to a shelter/den. This natural site could be a good area for deer to rest as Eastern Hemlocks works as a shelter from the weather and precipitation.

Posted in 2/4/19 | Leave a Comment »

possible weasel habitat/hole

twig sketch of an American Beech

tracks of a bounder, possibly a Short Tailed weasel

deer track

Posted in 2/4/19 | Leave a Comment »

The natural area of Centennial woods was originally inhabited by the Abenaki peoples of Northern Vermont. Parcels of the land were acquired by several different land owners including Baxter in 1891, and more recently from Unsworth in 1968. This piece of now protected land is managed by the University of Vermont environmental program. Centennial woods is made up of 70 acres of mature coniferous stands, which is displayed by my specific site. It also contains wetlands, fields, streams, hardwoods, and a well-used hiking trail.

Posted in 12/8/18 | Leave a Comment »

Cascades Park in the Style of Aldo Leopold

The air is still, but there is life here. The path slopes up as the trees thicken and breathe. This land is practically untouched, as if I am the first to encounter it. Ice that once filled a small stream spirals up the trail, and I can almost hear its frozen roar. The sea of trees is enveloping me into this space, as a Yellow Birch appears distinctly out of the cold earth. Around it, four Eastern White Pines guard the site. Placing a hand on the tree’s trunk allows me to feel its pulse, its life force. My footsteps are the first here, the snow is almost warm, yet firm when disturbed. The calls of a Black-capped Chickadee can be heard in the distance, her calls are seldom answered.

The leaves of the White Oak contrast against the white expanse of land. The deciduous trees are in dormancy, while conifers thrive. Beneath the trees, a stone wall stands, dividing the land. Its sturdy design houses creatures in search of shelter. It shows us the history of this place, how it served those before us, and how it’s changed since. This piece of nature was used for agriculture, and then left to rebuilt its beauty. The rush of the distant cascading waterfalls adds to the ambiance of these hills, as life continues to grow and change.

Comparison of Centennial Woods to Cascades Park in the Style of Wright

As I trudged through the icy path of Cascade Park, I was reminded of a familiar natural space far from home. Although states away, these places share many qualities. When I walk through each space, the air feels crisp and clear, as if I hadn’t been breathing before my arrival. In Burlington, the shade of the Eastern Hemlocks cloak my presence, and the needles create a new layer on the forest floor. In Worcester, the sunlight penetrates the earth, and I am odding alone in an array of still life.

When I last explored Centennial woods, I sat beneath the almost barren Red Maples, watching as fall prepared for departure. The reddish soil beneath me gave support as I carefully listened to the sounds of busy squirrels preparing themselves for winter. By the time I came upon Cascade Park, winter weather had froze over the existing soil, preserving it, while showcasing the fallen leaves of Maples and American Beeches. This land had given me a different kind of peace. Hearing my own steps crunch through the snow gave me an awareness of my presence in nature. Both places deliver me to a safe place, where nature evolves and understands, and where unquestionable beauty exists.

Posted in 11/26/18 | Leave a Comment »

Posted in 11/26/18 | Leave a Comment »