The increased prevalence of autism over the last several decades has been widely reported with rates now peaking at around 1 in 68 children, according to the CDC. This rise has triggered alarm in many circles as well as mass speculation over its potential causes, including the widely discredited hypothesis regarding vaccines. Tempering this concern, however, is the commonly held view that what appears to be a new epidemic probably isn’t, and that the increase in number of cases is mainly due to three main factors, namely 1) increased awareness and screening of autism, 2) a shifting  from other developmental diagnosis to autism over the years, and 3) a reduction in the severity threshold for what qualifies for an autism diagnosis. Regarding #3, this means that the diagnosis used to be mainly reserved for children who manifested very apparent and severe symptoms but more recently has been increasingly invoked for individuals with much milder, although still impairing, challenges. Yet despite the broad consensus about this hypothesis, direct evidence to support it has been lacking….until now.

from other developmental diagnosis to autism over the years, and 3) a reduction in the severity threshold for what qualifies for an autism diagnosis. Regarding #3, this means that the diagnosis used to be mainly reserved for children who manifested very apparent and severe symptoms but more recently has been increasingly invoked for individuals with much milder, although still impairing, challenges. Yet despite the broad consensus about this hypothesis, direct evidence to support it has been lacking….until now.

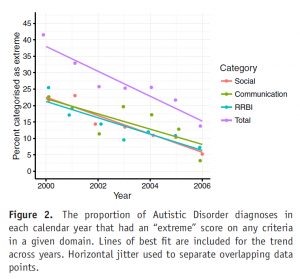

Researchers recently published data from an Australian registry that contained information on new autism cases between the years 200 and 2006: a time during which the rate of autism rose sharply. The official diagnoses in these cases came from a standardized procedure and included an experienced clinician’s rating of the severity of individual symptoms as mild/moderate or extreme. For a portion of the sample, the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scale was also performed.

A total of 1252 cases were analyzed, all under 18 years of age. The main finding was that the number of individuals who were rated as having extreme levels of many diagnostic criteria, or who had extreme levels of any symptom, dropped significantly over the study period. The percentage of individuals who had an extreme rating on any symptom, for example, dropped from 38% to 15% over the study period. Scores on the Vineland scale also dropped with time.

The authors wrote that theirs was the first study to demonstrate directly that the severity level of symptoms among people newly diagnosed with autism has been decreasing. They suspect that this phenomenon underlies what appears to be an increasing prevalence of the diagnosis.

In some ways, this is a study that proves something everyone already knew. Nevertheless, it is important to have some solid data behind a claim that is hopefully reassuring to most people. At the same time, the data underscore some new questions. Is it good thing to use this diagnosis for less severely impacted children? Does it open the door for needed services or cause unnecessary stigma while taking away resources from those who may need it most? The study also cannot rule out the possibility that a “true” increase is autism is also occurring, albeit at less striking rates.

Reference

Whitehouse AJO, et al. Evidence of a Reduction over Time in the Behavioral Severity of Autistic Disorder Diagnoses. Autism Research 2017; epub ahead of print.