I am laying out my involvement with Complex Instruction by telling Dottie’s Story. Dottie was a senior in my student teaching seminar. Each student was required by me to complete and teach a full CI rotation which necessitated completing a status assessment of their class, preparing their class for collaborative work, learning how to do the two CI status treatments (The Multiple Ability and Assigning Competence treatments) and assessing the content gains of their students following the rotation. The students had to document their CI work and after reading Dottie’s articulate exposition, I asked if I could use it to write her story of learning how to “do” CI, accompanied by comments by me. She said yes and this chapter of my memoir is the result. CR

Dottie’s Story

Complex Instruction: Social Justice In Action

************

Every class I teach is special for its own reason. These end-of-semester classes are most special. I get to see how successful I was by hearing about how successful they were. “They” are my senior teacher education students, ten of them now gathering with me in 426 Waterman. My ten seniors are hours away from completing their student teaching and light years away from where they were when they walked in the door the first week of September. During their senior internship, they enroll in Principles of Classroom Management and Organization, a required two-credit class. The most special part of this course for me is these final hours of our time together, for I get to see if I’ve been successful in meeting my deepest professional commitment. It’s crunch time!

Usually, I am the first one through the worn, oaken double doors of 426 Waterman. Thirty-four years ago when I began my teaching career at UVM, my first office was twenty feet away from where I sit now. The room has the barren quality of a university classroom shared by many, belonging to none. In my years at UVM, I’ve seen three different incarnations of this teaching space. Today, it is a rather non-descript, wired, anyone-can-teach here classroom. It’s the kind of room where you just know the night crew will restore the tabled chairs to their proper rows, once we leave our circle. Today, I’m only ten minutes early and some of my student-colleagues are already here. They’ve drawn the chairs into a more or less even circle. It’s casual; a few empty chairs for books, a chair or two in front that serve other purposes. Christian rests his feet on one and Rebecca has her books and bags and take-out on another. Most students are casually dressed by this time in the afternoon. They’ve exchanged their teacher clothes for campus dress before coming on to class. Hollison, Sean, and Stephanie enter breathless a bit late still dressed in their teacher clothes, having once again had to search for a parking. The three-story climb to our room has exacted its usual assessment of fitness.

I call them student-colleagues because we work together on this agenda of student learning and achievement through enlightened classroom management and organization. I’ve told them I want to work through them to effect achievement gains in their students; that we are to be colleagues in that effort. I do this by teaching my students how to recognize several sources of bias in their classroom that originate in the status order shared by their kids. The heart of this work is sociological. I teach them how to see and manipulate social and academic structures in their classrooms to minimize the negative effects of unequal status[i] among their school children. The end result I expect is for them to show me that each one of their students has been able to generate higher rates of learning. I tell them I can show them how, but they will have to contextualize what I show them and make it work in each of their unique situations. I know in their eyes they invest me with the power of University professor, and therefore, especially this early in the semester, they’ll play the ubiquitous schooling game and do what I say. Nevertheless, I work hard at this idea of equitable colleagueship. Until these final hours, most of them take my rap as professor talk. “We’ll see,” they say. “My kids don’t even work in groups and he wants us to do this complicated cooperative learning project?” But I persist. I know what will work. They know their classrooms. Together we will make the difference. If we do, my number one professional obligation will have been met.

I’m ready. I’d like to say for the drama if nothing else that these moments are the high points of the semester for me. But they aren’t. Every class I teach has certain high points. But this class is a culmination. If I’ve done everything right enough in teaching them the intricacies of organizing and carrying out status interventions during their complex instruction rotations, and if they’ve been able to gather enough instructional time over four or five days to carry out the rotation, and if they’ve managed to avoid fire drills, boiler breakdowns, snow days, flu epidemics, and excessive pull-out programs, I know they will be showing each other class content gain scores that will range from 25% to perhaps 85% calculated from pre/post analyses of content acquisition on their teacher made content assessments. They will show each other, and I wish the world at large, that despite all the usual reasons cited for why kids can’t learn – poverty, disability, shyness, parental dysfunction, low mental functioning, bad days, girls vs. boys, race and ethnicity, and so on – despite all the usual reasons, everyone learned something during their CI units; and, they will be able to point out that the kids least expected to perform well will be proven to have outgained the usually high performing suspects. That is my goal. Nothing less will do. If I cannot accomplish this through them, then I feel I have failed them and their kids in school.

This semester, I tell my seniors that our work together will be in part, social justice activity. It is clear from their halting discussion of what they think this means that the idea is a stretch for them. I know it’s hard. They are so focused now on just getting through a lesson successfully and being able to transition to the next part of their days without losing kids, to also have to consider their work a bold confrontation with some of our school’s deepest and most troubling issues is a tough stretch for them. But they acknowledge the possibility with me. They all agree, every one of them, to work with me on this mission and in fact, each one of them grants me permission to use any of their written work to support my own inquiry into how this social justice work happens. I’m a bit surprised, and exceedingly grateful. I want to diminish the importance of their agreements by saying perhaps its just the student/teacher power differential working itself out. Their agreement is necessary to grade highly in this course. But I also think they are curious about being able to do something they’ve heard a bit about across their years in our program but only now have to confront and take it on as their own. We are also beginning to forge our own working relationship on behalf of their students.

One such student is Hillary, a kindergartener in one of Burlington’s urban elementary schools. His student teacher is Dottie, my senior student colleague in this CI project. Early in our semester together, I asked Dottie, along with all my other students, to describe the learning environment in her classroom by focusing on the intersection of her kindergarten’s academic and social structures.

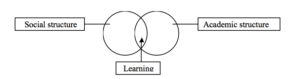

I provide a protocol for this that requires Dottie to identify the status order among children in her room. Status order is “an agreed upon social ranking where everyone feels it is better to have a high rank within the status order than a low rank. Group members who have high rank are seen as more competent and as having done more to guide and lead the group” (Cohen, 27). I want Dottie to know that the interpersonal social order in her classroom can be quantified and that quantifying it is one way of gaining some control over it[ii]. I work from a research base that has established the relationships between a child’s status among peers and their opportunity to learn and achieve. When it comes to learning, Dottie has to work hard to equalize the status among her youngsters as much as possible if every child is to have an opportunity to learn. “A genuine learning situation … involves the emotions of the learner; the social conditions in the group determine whether the necessary emotionality will be facilitating, distracting, or inhibiting of learning. …Successful methods of teaching do control emotional phenomena or “group process” in such a way that learning is better motivated, challenge is greatest, and accomplishment is the goal of the group (Thelen, 47). ” If Dottie is blind to the social conditions operating within her group of children, the kids who are the stronger learners “naturally” in her class (high status) will continue to learn and will dominate small group academic work. If she is blind to the interactions between social and academic structures, the kids who are perceived to be weaker learners (low status) will begin to see themselves as academically unable in Dottie’s room. They will begin to form a self-fulfilling prophecy that becomes a freefall into academic and educational failure by the end of fourth grade[iii].

The bias that is present here is that most schools place high value on the skills and dispositions related to print literacy. Children who are good readers and writers have a higher chance of doing well in school than children who are mediocre or poor readers and writers. And even though schools generally work hard to ameliorate the cause of mediocrity, the children who become the foci for those activities are often identified and labeled and set apart from their peers in the process, at least from the peers point of view! So biased views and perceptions of these children’s overall capabilities and dispositions are built into the social system in such a way as to disadvantage these children in ways that move way beyond literacy work. Systemic bias of being “unabled” is attached to them and soon, they begin to believe it themselves. It is this perception of “unabledness” and the systematic bias that results that my students and I intend to ameliorate, at least in the short run. I want Dottie to have more than my opinion or her own systemically informed judgments to plan interventions for Hillary. I wand Dottie to have data; data that reveals to her that even though her children might learn how to be “nice” to each other in their countless daily social and academic interactions, other more powerful factors affect each child’s opportunity to learn, most notably the factor of where you sit in the classroom status order. Once I am able to teach her how to recognize how these dynamics play out with regard to group process, status among peers, and ability to learn, I can then teach her how to structure small group cooperative interactions that use the relationships between status, learning, and achievement to the advantage of every child in her room. This is how I prove my worth to myself. This is my lever into changing the effects of group bias, whatever the group is, that infects Dottie’s class. This is how I perceive my job and prove my worth to myself as a teacher educator.

Arrogance? Perhaps. But I don’t approach it as such. At least I don’t think I do. I face a group of students who are consumed with their placements. What I have to offer is in many ways, an afterthought to them. A requirement to be fulfilled. They have to leave the challenge and excitement of a high-stakes internship placement and come to campus to spend instructional time with me. Truth be told, I believe, and research confirms, that 80-90% of them would rather just stay with their mentor teachers in their field placement, surrounded mostly by children who feed their own need for acceptance, identity, and confirmation, thank you very much. So my invitation to them is to be a colleague, united in an effort to combat systemic discrimination that is surely larger than both of us. Neither of us can do it alone; together we can be more successful. And in the process, together we will have sewn a few squares into a quilt of social justice that binds us all together as quilters of perhaps a more perfect American fabric.

Serious? Definitely. I’m pretty good at giving them systems to work with behavioral challenges and we do that first in the course so they do begin to think I have something useful to offer. The jaw-dropping experience for them is when we do the sociometry for status order. Most will assert that their teachers recognize and work on the importance of teaching kids to respect one another and be nice to one another in the daily ins-and-outs of classroom life. Through the eyes of my students, most of their mentor teachers work hard on this and are often quite successful in their efforts with most kids. When I ask my students how their teachers work with the “whole child,” most will respond that the children’s emotional life is dealt with through morning meeting. Morning Meeting is part of a set of procedures built into The Responsive Classroom, a way of organizing your classroom advocated by the Northeast Foundation for Children. Many of my students will do activities with their cooperating teachers during the first six weeks of school that are designed to create supportive and encouraging communities of learners among their kids. Responsive Classroom methodology is a powerful set of strategies that does in fact address the social-emotional life of children. Still, not every child makes it into the fold. My students readily admit they have kids who remain disconnected from the important work that goes on in their classrooms, classrooms where most of the time everyone is “nice” to each other.

The kids with whom they are less successful in these efforts are, well, “those kids.” Those kids for whom parent background, upbringing, genes, social disorder, emotional challenges, or lack of maturity will never be socialized the way they should be. In one moment, my student colleagues tell me they can see how certain children’s social immaturity affects their academic opportunities. When they mention “Responsive Classroom”, they assert their classrooms have academic and social structures that deal with these social misfits. Their next sentence is almost predictable. It relates to the really difficult kids; those kids who seem to live a world predestined for failure. The sentence goes something like this. It denotes the place where teachers often wash their hands of the most challenging children. “There are just some kids who you can’t reach. Who can’t or aren’t able to take part in the academic and social life of school.” And then, almost as an afterthought someone will say: “ But everyone at least has some friends in school and if we are nice to each other, at least they experience some friendships among my children.” It is as if schools are destined to have some children who will fail and that we can be sensitive to their needs but there is only so much we can do. It hurts, but it’s true.

So when the sociometry is done and the status order table is built, my student colleagues are often stunned to see they have children who have zero status in their room. Zero. None. This means that not one child has selected them either as a friend or as an academic helper. Almost every one of my student’s classes has at least one or two children who will not be picked once as a friend by another student in their class. Not once. These low status kids are perceived by their peers as having nothing to offer to what goes on in their classroom. It is as if their peers are saying, “We’ll be nice to you if we have to, but that’s as far as it goes. When it comes to classwork, and playing games, and walking hand-in-hand to music, I’d rather not! You are a non-factor in here! ”

Hillary is a zero status child in this kindergarten classroom. Here’s a shortened version of Hillary, using Dottie’s words, composed by me.

“Getting my way.”

Won’t do what I wanna do?

I’m gonna get a new friend.

Can’t make me.

Put me up in front of the room?

I’m gonna shut right down.

Can’t make me.

Tell me what I’ve got to do?

I’m gonna wait til the end.

Then rush rush rush,

Won’t do the work.

Will you help?

I don’t know what to do.

Can’t make me.

Call me shy?

Call me procrastinating?

Call me worried.

Call me demanding.

Call me getting my way.

I am powerful.

I will fight.

(I can do this work you know.)

I am un-chosen.

Hillary is an academically able child, struggling in these opening weeks of kindergarten when Dottie does her status survey. In the vignette she includes as part of her first class assignment, Dottie describes Hillary’s learning.

Hillary has many different sides to her. She is very shy at first. The first couple of weeks she won’t play with the other children. She is always asking an adult to play with her. She is an only child and is not used to the idea of sharing. She’ll often try and take what the other children already have. When I go over to talk it out with them she tends to shut off and not listen to the other student. She has friends but it changes when the person she is playing with won’t do what she wants. She is an overall really happy girl and plays the games [we do] with the other students. She just has a demanding demeanor that often causes fights between the students. She is strong academically when she wants to be. But she has a hard time focusing on projects she doesn’t want to do and will often wait until the very last minute to get her work done so when she know she is running out of time she will rush her work. It’s hard to assess her because we know she can do it but she just won’t show it all the time. When she is around certain students, there is a power struggle that takes place for most of the lesson and this effects (sic) the type of work that Hillary produces. When she is in front of the whole group is when she normally just shuts off.

Dottie chooses Hillary as one of four students she will to focus on during her CI work[iv]. Her reasons? Dottie shares, “The four interesting students that I chose were from the highest, lowest, second to lowest, and middle of the status order. I felt these were good selections because a couple took me completely by surprise, and the ones that didn’t need a specific plan to encourage their learning in the classroom.” Hillary is one of the surprises. One of those children who can do the work but doesn’t, who can relate to peers but only if she gets her way, is more comfortable in the world of adults than the kindergarten world of peers, and who is clearly at risk for a kind of permanent group exclusion. That is the message of her placement in the status order of this class. Voodoo death[v]. If this attitude gets established between Hillary and her classmates, they will decide not to admit her to their discussions and deliberations. They will not even listen to her offers of assistance in group projects once they decide she has nothing to offer. With a zero choices on the status survey, that process I believe is well under way.

Dottie’s sees Hillary’s social issues. Then, she makes several connections to the academic effect of these social issues. Hillary pulls out, shuts off, procrastinates, rushes through when compelled to finish. Not a very good beginning to school and Dottie, in her choosing Hillary as a focus child, decides to see what she can learn about how to improve things for Hillary. In her teacher’s words, Dottie decides to see how she might manipulate the social and academic structures in her room so as to change the expectations for inclusion and actual learning behaviors of Hillary and her peers. Dottie will try to change the behavior of Hillary and Hillary’s peers by planning a complex instruction learning environment in her classroom for a bracketed period of time before her internship is out.

I will teach Dottie and her colleagues how to design a social and curricular intervention that will give Hillary and all her peers a different reality of Hillary’s academic capability. Dottie will go beyond establishing a climate of educational opportunity. Dottie will create an intervention that has a very high likelihood of revealing Hillary as a successful contributor to academic group work to herself, certainly, but most importantly, to her peers. The overall effect Dottie will aim towards is that her peers will be more likely to give Hillary access to their shared academic pursuits, and Hillary, having seen that others value what she has to offer, will be more likely to turn on to shared work rather than turn off.

If successful, Dottie and I, in my mind, will have committed an intentional act of social justice for this one child in this one classroom. We construct the quilt one stitch at a time. We will have committed an act to counteract the attitudes and behaviors that led to the horror viewed by that seven year old boy in the great red book so many years ago. This is one way I play out my ally role with my African-American colleagues. I think Doris and Mary and Mannie and Mr. Burns and all the rest, would smile now. At least I hope so. But I’m not going to worry if they don’t. I know this work is my portion of our communal struggle. It’s direct, it’s person to person, and it makes the kind of academic and personal difference in the lives of children that satisfies my desire for professional self-respect and confirmation.

It’s now the end of September. By the end of October, I have to have my colleagues prepared and ready to carry out a unit of Complex Instruction. By the time they head into their time of maximum classroom participation, for most a two-week period of time when they totally run their classrooms absent their mentor teachers, they have to be as ready as they can be to do a CI rotation with a pre/post test analysis of content acquisition for every child in their room. That is a big order, conceptually, and then practically, speaking. My intention here is not to be instructive about CI, only informative. My goal is to be clear enough about what it is so Dottie’s work with her class and Hillary will be fully accessible.

The status survey gets my colleagues’ attention. Dottie saw that Hillary had academic challenges that were beyond his control. She had to alter both the social and academic structures in her classroom for some part of her instructional time if Hillary was going shift her learning behavior. The key in this process is that her peers have to alter their perception of what Hillary can do for them academically in order for Hillary to shift her behavior. Although it is still very early in Hillary’s academic school career, the patterns of her withdrawal and non-participation are being established in her classroom.

Dottie is faced with several tasks. She has to create four to six group activities that are open ended and address an essential question or big idea, interesting to the children, and are not able to be done by any one child individually. The tasks must require multiple intellectual abilities for the group to do them successfully and well. The tasks must be appropriately directed on activity and resource cards. Then, she has to divide her children into four to six heterogeneous groups, and free up enough classroom time for each of the groups to do each of the tasks on successive days on a rotational basis so every group gets to talk and work together on every task over a bracketed period of time. All this has to be done after teaching the kids that they can be real resources to one another in classroom academics, that together they are smarter than any one is individually, and that they have a responsibility to help each other and the right to ask for help when any person needs it. If her class is unpracticed in group work, then Dottie has to devote time to teaching the kids how to work together in a group, prior to the CI rotation. She will also have to decide what she wants the children to learn as a result of her CI rotation and design an assessment that can give her pre/post data on content acquisition tied directly to the big idea.

This is a tall order. The fact that I find my undergraduates more open to its challenges than many practicing teachers is interesting. That’s one reason I’m successful at what I do. Like the little boy in The Polar Express, when the bell of learning for everyone rings, most of my undergraduates still hear it. Most have an idealism that really wants every child to be recognized as a learner and they all have received their education to be teachers in a program that works hard to teach them how to take advantage of the many abilities children bring to the learning tasks in school. We work hard to teach them how to go beyond reading and writing and computing as the only way pathways to school success. My undergraduate colleagues are also less convinced than many of their older counterparts that some kids “simply can’t work in groups.” There may be a kernel of truth here, but if there is, it’s true for far fewer numbers of children than teachers would like to consider. Probably half my undergraduate colleagues will have mentors who do little or no group work besides asking kids sitting near each other to “help each other” with what they are doing. “It’s too hard,” I hear. “And besides, this particular group of kids just can’t get along with each other.” In my eyes they’ve accepted the social structure that walks in their classroom door and consider themselves impotent to shift group dynamics in their classroom. In CI, we dare to influence classroom social and academic structures so that all kids collaboratively participate at higher rates in ways previously thought impossible. Dottie’s first task is to teach her young charges some collaborative skills. When she heads into her rotation, she doesn’t want to be teaching them how to work together for the first time as well.

This semester, Dottie’s process was being replicated in nine other classrooms as well. I use portions of every one of my classes to prepare them for some aspect of this work. It’s a daunting task. But I know that if they can manage and organize themselves and the class to be ready for the rotation, they know about and are able to execute a set of principles and practices for classroom management and organization that will remain with them for a long time after leaving UVM.

This is hard work for them, and its hard work for me. It isn’t easy moving against the grain of instruction that predominates in most of their classrooms. I have to keep their interest and they have to trust me that things are going to work out. I have to recognize that I’m not the most important force in their lives and that our classroom work may be way out of phase for what they are being asked to do in their classrooms from week to week. On the other hand, I work with them from week to week on interventions that will help them be better manipulators of the group process in their classrooms: running effective classroom meetings, playing fun games that also teach collaborative norms, sharing words of encouragement (vs. praise) that they’ve given their kids with each other over email during the week between classes, adjusting required curricular tasks to take advantage of kids’ multiple abilities, working from success, not failure, teaching and building collaborative skills, playing broken squares and other games that show the need for group process, teaching them how to point out to all the children in a room the special abilities of one child in a room and to do it in a way that causes the other kids to want to work with the one child. Every class, for at least some of the class period, what we do continues to put before them ways to better equalize status differences among children in their classrooms so as to enhance the academic work that results when kids can more successfully talk and work together about content of academic import.

If there’s anything I worry about, its am I being tough enough with them. Am I requiring enough accountability for them on what I think is important? Are they just going through the motions with me? I have a syllabus, and it frames our work over the course of this semester. But I’m not teaching a syllabus. I’m teaching twelve mostly 20 or 21 year olds who are very busy in the pretend-work world of teaching. Like the gambler, I have to know when to hold, and know when to fold on certain of my requirements. But I’m always doing it with an eye to what they are going to be able to do with those kids in their classroom by the time they leave me prior to solo weeks. When we arrive at that point of the semester, I won’t see them for three weeks and by that time, it’s over, it’s really over. They will have carried out their rotations, done their status treatments, and calculated their average class content acquisition gain scores before they return to me. No one is fully ready to go when we say good-bye that last class before solo. By the time they return for our final two sessions, everyone has done all they can.

Two more class sessions left. They sit in that more or less perfect circle except its more disheveled now. Books scattered about, water bottles and munchies on most of the desks. There’s an air of almost cockiness about them, those who have completed their CI work. I’m a bit on the edge of my seat as they begin to write about how it’s gone in our warm-up activity. I’ve been in email contact with perhaps two-thirds of them during the interim time period. I met with four of them to do further preparation during the interim period. But it’s the first they’ve heard colleagues tell of how successful they’ve been, especially their colleagues from other schools. And sharing with me and sharing with each other is a whole different dynamic. Even at this point in their career, they are still very young adults and it isn’t too cool to stand out in your group as being outstandingly successful. It’s almost easier to share your adaptations when things don’t go so well. I love hearing both. Each underscores an ongoing reflectivity that underscores another one of my pet beliefs, the one that goes something like this: most learning problems are in fact, teaching problems.

Dottie shares excerpts that appear in her final paper. Her words, and the other eleven versions of them, provide evidence for my success or failure. She has constructed her kindergarten rotation around the big idea of Community: Who and What Belongs In Your Community?, a piece of kindergarten content strongly suggested by Vermont’s Framework of Standards and Learning Opportunities.

Before doing the complex instruction, I had practiced some group work with my students so they could get a hold on what it was like to work as a team member. In kindergarten the students are so egocentric that they only think of generating their own project using just their ideas. …After the task we talked about what it is like to work as a team and what it was they learned that will help them out.

That’s good. She took to heart the need to prepare the children for a more formal style of working with each other. When I teach this, my students will inevitably nod that this is important. Finding the time to do it is quite another matter. That Dottie has done this with five year olds is quite impressive.

The week before the complex instruction rotation started I slowly began to break the students in to the basic roles that were involved. The roles that I had them fulfill was (sic) the recorder, reporter, materials manager and the facilitator (I called the referee because they were familiar with that term). They pretty much knew what the jobs were for the most part and how to do them. …

Good for her. She’s adjusting immediately to situate this work in her own context. She’s making the names more accessible to her young charges.

On Monday I first started my orientation by going over the roles again. …Then I brought them through all of the different activities that they would see throughout the week. I brought them from bin to bin so that they were moving around because we had spent a little bit of time sitting talking about the roles and the end result. Then it was time for the students to receive their roles. I had made little cards for them for their jobs. I called each name and gave them their special card. Then their materials manager had to find the right bin for their group and bring it to the table. Finally the complex instruction had started!

The role cards are absolutely essential and they seem like fluff when I first introduce them. Students think their presence is merely window-dressing. Yet children, especially young children invest great import in the cards. I’ve known almost silent children who come alive because this badge of role gives them permission and need to speak. The “little cards” are one of the levers that forces a place for talk to occur.

At first on Monday my students didn’t quite understand how to split up responsibilities between each other to make just one project. They were so into making their own products that that is what their first instinct was to do. Through a couple of friendly reminders and a little redirection they got back on track. That day the students weren’t so sure of their roles either. They knew their names and knew what they had to do but they didn’t know just how to do them. …Once of my groups took the recorder to a whole other level. They had their recorder make the labels for their community helpers. On Monday, my mentor teacher and I were involved a little more than each one of us had planned. We had talked a lot with each group about the roles, the desired product, and how to involve everyone in the group. …They all said that it was fun and we brainstormed some ideas on how to listen and how to make two ideas into one.

You definitely get the sense here that Dottie is butting into the groups more than she would like. First days are like that, even when I work with college students and adults. No one reads the activity card directions first. Materials hit the table and bang, top’s off and hands are into the materials. What Dottie did was exactly right. In the wrap-up to this first day of rotation, she gets the children reporting on how things went and in the report, others can see that there’s certain way to do the activities. This is important for the days that follow.

Tuesday they were ready and really excited to move to the next activity. We reviewed the roles that each student had. They we went over the different activities and talked a little bit more about completing only one project between (sic) the four or them. During this activity time the students were getting used to the roles and I began to see them ask the right person in their group to go get the materials, the reporters were always persistent about being the only one talking and the recorders wanted to do all the writing. I was seeing how the roles were falling into place for some of the groups. They were finally coming together as a group and talking to each other to make their project. That is when I realized that the roles were important but I wanted them to first get down the idea of working in this group and talking with each other to be successful in their group. They weren’t shutting anyone out, and as far as I could see everyone had a hand in all the tasks. It was after this that I realized that group work was enough for some of them to handle without the pressure of the tasks.

Dottie shows her mastery of the routine here. Orientation, learning activities, wrap-up. She adjusts her expectations some as she seems the group bonds begin to form. She shows that she’s able to step back and learn what’s going on for the kids as they begin to take responsibility for their learning. In CI language, Dottie is delegating her authority to the kids as they become more responsible for taking it on. She is also showing that she has to delegate before they see that they have to take it on.

Wednesday the students understood the tasks much clearer and they were still working really well in their groups. I changed one rule because I felt like these kindergarteners wanted so badly to express their own feelings about their project. I had the reporter do the initial reporting to the whole group and then after they were done, I said, “Does anyone else have anything to add?” This allowed all of the students to have a say in the finished project.

I think what’s interesting here is what Dottie doesn’t say. The work goes smoothly on Wednesday. This is only three days into the actual rotation with her children. Five and Six year olds. Doing groupwork, together, successfully. She doesn’t recognize this as a significant achievement, either by her or by her kids. It’s almost as if – to quote James Herdon’s famous line – this is the way it “spozed to be!” What I read here is that for these moments in time, Dottie has crossed over. She’s on the other side of the bridge looking back at her colleagues who say children can’t do groupwork. She knows now that they can, the evidence is in front of her, and its so expected by her that its recent rather smooth emergence merits not a mention. What she does mention is her effortless monitoring and adjusting to ensure that all the children can have a say during the wrap-up. That too, is the way its “spozed to be.” Its just that some novices, in the beginning of trying to implement CI in their classrooms, assume too rigid an interpretation of the role assignments. In CI, every child has at least two responsibilities: one, to fulfill their role function, and two, to add their voice to the solution of the groupwork challenge.

Thursday, the last day of the rotation, was the big challenge! I told them I wanted to intervene as little as possible. If they needed something then they had to talk with their group members and work it out by themselves. I felt like their group work was efficient enough that they could meet this challenge. They all knew just what to do and they went right to work. They started off asking me questions and coming to me with problems and I simply just directed them back to their group members for help. Most of the groups were able to work as a team and finish the task. At the end of Thursday I congratulated them for all of their hard work and willingness to try something new with me.

The young teacher’s voice comes through here. Dottie has made it. All this work has paid off. The kids have successfully taken on the CI work and her relief at the conclusion of these interventions is almost audible.

Throughout the rotation I was able to walk from group to group and talk with them about what they were doing. I assigned competence within the group at the time and then again when we gathered to share as a whole class. One of the instances that I assigned competence was within a group to a boy who was using his words with his teammates very clearly about what he was thinking. He was expressing what he was thinking and then someone said something else and he worked with the other kid’s idea. This allowed the group to work with his idea and yet still incorporate other’s thinking. …

Assigning competence is one of the powerful status treatments in CI. It assures the other kids note the skills and abilities certain kids have, especially the low status children, that enables the group to finish its groupwork successfully. The assignment of competence is designed to boost the probability that the higher status kids will invite their more silenced partners into the active learning of the group. Dottie’s description shows its powerful effect.

The different activities I planned had a variety of multiple abilities. Before beginning the first day, I talked with the students about the different multiple activities. The ones that I noted were painting, cutting, writing, reading, talking, problem solving. Throughout the week we talked about if anyone had used some of these abilities and everyone seemed to relate to them. We added only a couple to them. They were drawing, building, creating, and coloring. …

Dottie shows her knowledge of the second major status intervention here. When she posts the different abilities needed for successful Groupwork, the children see that no one ability (like beginning able to read or write) guarantees successful completion of the activity. Dottie has established a mixed expectation for competence among her children. By doing this, they learn that everyone must have a part if their groupwork is to be successful. Dottie then goes on to describe what she noticed with Hillary, the young girl that had zero status after one month in her classroom. I am fascinated with how Dottie reports what’s occurred with Hillary. She definitely has seen a change in group behavior.

There are two versions of success here. This is how Dottie sees it.

Hillary was one of my identified students. During the complex instruction rotation I gave her the role of being the reporter. This job was given to her because I felt that she could use that confidence in talking in front of the group. She had a big responsibility and she had to talk with her group members to know what to report. Hillary has a hard time working with other students. When things don’t go her way she tends to throw fits and get angry with the other people in her group. The beginning of the week she started off by not working with her team members and doing what she wanted to do. As the week went on she was able to work together with her group members in a meaningful way. During the Groupwork she learned how to talk with students instead of getting angry if things didn’t go her way. By her throwing fits the students didn’t want to work with her and then she wouldn’t be a part of the group. The effected (sic) the quality of her part of the project. During the rotation I feel that she slowly warmed up to her group and to the idea of having to ask her teammates questions instead of trying to do everything herself or relying on the teachers. Her reporting skills became very strong, too. She was able to stand in front of the group and just report out what her group had done and she started talking with them during the presentation about what to report out. She was listening to the suggestions that her group members were giving to her.

So the “success” that is paramount for Dottie is the shift in Hillary’s social relationships with the group. What Dottie chooses to mention as success is Hillary’s social progress. Interesting that Dottie doesn’t mention Hillary’s academic process. This is one of the most difficult areas to get across to my student-colleagues. They see the social needs so clearly. It is much more difficult for them to see and value the academic connections that all of CI is geared to achieve. Academic success is the point of CI, and that’s what I choose to emphasize as the ultimate success of this structural renovation of Dottie’s class.

I would offer that social acceptance remains paramount for Dottie for two reasons. The first is that Hillary can be a child that disrupts the order in Dottie’s class. To have Hillary finally contributing meaningfully during class time is not a small item just in terms of classroom discipline. Clearly, it’s important to Dottie as the young teacher. I would also venture to say Hillary’s more sophisticated way of interacting with the group is important to Dottie because developmentally, Dottie herself is still working through their own issues of identity. They are at the end of adolescence. They are coming to the end of college. They are concerned about their jump into their next world, the world of full time work, the years after college. They have a special sensitivity to what their positions will be relative to group membership because their memberships are going to change for them very soon in profound and significant ways as they get on with the next portion of their lives. No wonder group issues remain important developmental work for them. No wonder, for Dottie and her colleagues, academic gains take a back seat to increasing social interest on the part of their young charges. Academic gain is almost an after thought. This observation isn’t only about this group of ten young adults. I see it in all my college student classes. How they affiliate and interact with the various groups in their lives is very important stuff!

For the record, here’s what happened to Hillary academically. Hillary went from a score of 2 on her pretest to a score of 8 on her post-test for an overall gain of six points. The average gain for the classroom was 4.8 points. The average gain for Dottie’s lower half was 5.1 points. So not only did Hillary outperform the class average, she outperformed all the other kids in her class who were low performers on the pretest. She found her academic voice because she learned to get involved with the group work. She got involved with the group work because the other kids saw she had something to offer. The “other kids” saw she had something to offer because Dottie had manipulated the social and academic structures in her classroom to make it happen. Together, they all learned more.

Hillary is a schoolchild who is better off for what I do. At least this statement is true in the way I choose to define “better off.” The results of this collaborative effort between Dottie and I is that Hillary has experienced for this CI rotation a new reality in terms of her classroom interactions with this CI rotation. Dottie has shifted the social and academic structures in this classroom so that Hillary experiences academic success with the tasks. Furthermore, her academic competence is affirmed by Dottie and her classmates, she experiences her contributions being valued, and she is able to stand in front of the group and just report out what her group had done and she started talking with them during the presentation about what to report out. She was listening to the suggestions that her group members were giving to her. This entire effort, Dottie’s and mine, has academic payoff. Hillary’s contributions are clearly worth something to her peers, and as a result, her peers perceive her as a useful contributor to their efforts as well.

One of Dottie’s peers puts it this way.

I could not believe what the kids were capable of on their own, working out problems by themselves. NU and CR were able to let go of their controlling personalities, and get to know students they normally would not. SM and KP were able to show who they are during the group work, with the assigning competence, and with the presentations at the end. This was a chance for the children to not only work together, but to learn about each other, it was a way for them to solve problems on their own, and therefore feel more independent and capable of solving problems in other areas. After that first day I could see the purpose of doing this type of cooperative grouping, and I am definitely going to use this again when I have my own classroom. We will never know what the children are capable of doing if we don’t put the task in front of them…and show up incredibly prepared and organized.

Perhaps the same might be said for me. To leave children in the schools better off for what I do, I need to put the task squarely in front of my students, plan early and often, show up incredibly prepared and organized to teach them what they need to know at the point they are ready to learn it, have a clear, mutual goal to problem solve together, and keep the pressure on.

For this group of ten students, eight were able to carry out their pre/post test analyses of content acquisition in their classrooms; Christian ran out of time because of sickness, and Sean was prohibited from doing the analysis because his mentor teacher did not want to engage the children in this kind of assessment. All their projects spoke poignantly to the social interactive growth of those students they’d identified as non-participators. In de-briefing conversations our final day of class, all but one reported they simply didn’t believe this would happen, especially those whose mentors saw groupwork as a mighty risk.

I expected these augmentations of talking and working together. I’ve done this enough times with enough students in enough different classrooms to expect changes in the social interactions within groups. CI creates so many levers to effect these changes. What I look for are the academic results. I can see the numbers are all in the right direction when I scan my student’s final reports. But I actually want statistical evidence that the differences I eyeball are statistically significant. If my students’ students show significant learning gains, then I am still on the path that began for me, I suppose, in that large red history book in 1949. If my students’ students show significant learning gains, then the decision I made the day I got sick to my stomach in the midst of the 1997 workshop on standards based mathematics curricula would be confirmed for another year. If my students’ students show significant learning gains, then I will have fulfilled my professional obligations for yet another semester.

Of the eight classrooms where the full cycle of pre-test, rotation, and post-test was comprehensively accomplished, seven analyses were statistically significant (Table 1. and Table 2.) Dottie, Rebecca, Lisa, Sarah and Hollison’s children showed significant achievement differences at the .0001 level. Molly and Stephanie’s students showed significant achievement differences at the .05 level. Sarah’s children just missed significance with a probability level of .055, Interestingly enough. Sarah was the only student who had to renovate her activity cards after day one of her rotations. Her cards were simply too wordy for her second graders. So in effect, her students had two day ones. Behaviorally, in effect, they lost a day in the resulting confusion.

Teacher educators, and this teacher educator in particular, can make a difference in the lives of schoolchildren. It is good to feel that success, once again. For one more semester, the children of my students were better off for what my students and I have learned to do. Together.

[i] I’ve been applying Expectation States Theory to my understanding of small group process for several years now. This helps my students understand the relationship between status and your opportunity to learn and achieve. In this theoretical base, your opportunity to learn is mediated by whether or not your peers think you can be an effective academic team player in their room. If they do, you’ll have an opportunity to talk and work with them in small group activities. If they don’t, your contributions will be ignored and your participation in the classroom work will decrease with negative academic results. The original work on status theory was done by Zeldich, Cohen, and Berger. Elizabeth Cohen as spent the last thirty years developing research-based interventions that minimize the relationship between status and achievement in small group activities. Cohen calls her form of small group collaboration “complex instruction.”

[ii] Each child is interviewed by Dottie to surface the status order in her room. She asks the children a set of questions, one of which taps friendship patterns in her room and a second which taps each child’s perceptions of the academic competence of his or her classmates. The status order in the room is simply an ordering of children from those who have been chosen most frequently (high status) to those who were chosen infrequently or not at all (low status). Cohen (1994) has shown that status in a classroom is a variable that depends upon how many of your peers choose you as academically competent and as a friend.

[iii] Many assessments of educational progress draw attention to the academic cliff that seems to exist in the upper elementary grades, especially for students who enter our schools from circumstances of dramatic economic challenge. This was first made clear to me in research carried out by Grant and Rothenberg (1981). Their teasing out of how “chat behavior” of teachers signaled a privileging of certain groups of children in their classrooms was one of the first times I really understood the depth of the presence of differential instructional environments within the same classroom. “The Fourth Grade Plunge” is a more recent incarnation of this phenomenon for me. No denial is possible, once read, of how our instruction places economically “different” children at risk.

[iv] I link the first and last assignment in my class. In the first assignment, students have to identify the academic and social structures in their room, identify and describe the learning behavior of four children who are either advantaged or disadvantaged by these structures, and think about academic interventions that might help the children classroom learning processes. For the last assignment, they design and carry out a complex instruction cooperative learning unit. All children are involved, but they focus on the four children they previously identified to guide their design work and assessment activities.

[v] Thanks to Dr. Chris Stevenson for this apt description of a schooling process that creates conditions of failure for kids who haven’t a clue. Their will to succeed dies as surely as if a shaman somewhere had consigned them to voodoo death.