Memory possesses authority for the fearful self in a world where it necessary to claim authority in order to Question Authority. Their may be no more pressing intellectual need in our culture than for people to become sophisticated about the function of memory. The political implications of the loss of memory are obvious. The authority of memory is a personal confirmation of selfhood, and therefore the first step toward ethical development. Patricia Hampel, p36.

America refused to be an idea. It was a country, and its national self – that personality Whitman tried so valiantly to identify – was emerging as national identity always does: out of history, out of circumstance and experience. Ibid, 59.

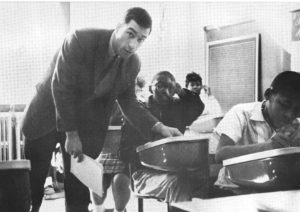

We are a new breed – a bunch of social reconstructionists which is the new place of education in the world. Are we to become a director of what is, or a director of what ought to be? The change-agent philosophy is interesting – get into the conventional system and become a friend. Then, influence change through your friendships. …The educational revolution will be accomplished only by work from within. We must lead our teachers, and not reflect them. (UTTP Journal, 7/23/64)

Living through the ’60s

If my time in Syracuse and the Urban Teaching Preparation Program were surely the moments of my life that I began to learn my craft (I still am, by the way), they were also the moments where I learned first hand that there were many Americas. I was late in life coming to this idea that many realities describe instants of time. But I came to it head on in Professor Christopher Lindley’s Semiinar in the Historiography of American History my senior year at college. James Beard’s An Economic Interpretation of the American Revolution revolutionized my thinking. Somehow, I’d always believed there was a “real” reality, and that deviations from it were just that, deviations. It wasn’t that I didn’t know there were multiple realities running around in this world. I’d seen that first hand in abnormal psychology. But the deviance strand was large there – “abnormal” to be exact. Beard and others opened up for me the idea that real life events could have many webs of causation and that causation could be a cultural, sociological, but finally idiographic phenomenon as well as an historical event.

Huge events swirled around me in the 1960s. During my upperclass years at Rochester and my years teaching in Syracuse, America’s historical register recorded at least the following. And every image came into every American home that owned a television. Black and white flickering images of an America increasingly at war with itself. An America struggling to put down insistent voices straining to be heard. An America fearful of itself. An America finally dealing with buried (for the white wealthy) issues of privilege and power. An American that was asking just who were Lincoln’s people? An American where people freely claimed that Lincoln had meant them! And even if he hadn’t, they were going to take what was rightfully theirs anyway.

Every night the evening news brought evidence in flickering black and white images that revealed the stories of different interpretations of what it meant to live in the “land of the free,” of who was to be included, and who wasn’t. The imagery appeared ugly and yet those images portrayed a search for perfection, both at the same time. The times inspired those who wanted things to remain as they were in the McKinley era of conservatism, and it inspired those who would destroy the US as we knew it if their voices remained silenced or unheeded. These were huge events. Are you old enough to remember? Have you heard conversations about? Have you seen the pictures of… :

- Woolworth lunch counters become known for something other than tuna fish sandwiches.

- John Kennedy beats Richard Nixon at the wire.

- Greyhound Buses carrying Freedom Riders are run off the road and burned by the Ku Klux Klan.

- The Berlin Wall goes up.

- Kennedy and Khrushchev face off over the placement of Soviet ICBM’s 90 miles from Florida. Kennedy wins.

- The Klan bombs homes and churches throughout the south. Four little girls die during Sunday morning church school in Birmingham, Alabama.

- Bull Conner runs roughshod over civil rights as his police set German shepherd police dogs on men and women, adults and children, who protest their lack of political power.

- John Kennedy is murdered in a motorcade in Dallas, Texas, Jackie by his side.

- America Jack Ruby fatally pumps two 38-caliber bullets into Lee Harvey Oswald, John Kennedy’s assassin.

- Tens of thousands assemble in Washington to hear Martin Luther King and others marshal support for congressional action related to voting rights.

- Congress passes the Civil Rights Act of 1965 and the Voting Rights Act of 1966 with Lyndon Johnson’s encouragement.

- Two Southern leaders, Lyndon Johnson and the Rev. Martin Luther King, talk.

- Johnson pushes through the Great Society programs. Head Start is born. The Elementary and Secondary Education Act is born. Entitlement programs to end poverty come on line.

- The bodies of James Chaney, Michael Schwerner, and Andrew Goodman are dug from an earthen Mississippi dam. Indictments occur only forty years later.

- Cassius Clay changes his name, resists the draft, goes to jail, emerges as Mohammed Ali, and wins the heavyweight championship of the world.

- Pictures of armed militant Black students taking over the administration building at Cornell University flash across newspaper wire services. Higher education is forced to look at its role, not only in terms of minority admissions but also in terms of follow up support for students who believe the keys to the academy are theirs as well.

- Clarissa Street in Rochester, N.Y. burns in what was the first of many urban riots across the country. Detroit, Watts, Newark, Washington, DC burn. Sol Alinsky works to organize poor urban communities to gain political power in order to stem random violence.

- Malcolm X goes to Saudi Arabia and returns, ready to renounce his brotherhood in the Black Muslims. He meets with King, once.

- Ministers of the Nation of Islam, pump seven shotgun shells into Malcolm X during a speech at the Avalon Ballroom in Harlem. Malcolm dies in the arms of his wife, Betty.

- 350 freedom marchers are tear gassed, beaten, and set upon by horses and police dogs as they cross the Edmund Pettis Bridge in Selma, AL. White supporters, church members of all kinds among them, come to Selma from all over the US and join King in the march for civil rights. Five days later 13,000 people gather in Montgomery to hear King and others speak from the Capitol steps (the “Moral Arc” speech). The march passes the Dexter Avenue Baptist church where the Montgomery bus boycott had begun ten years before. George Wallace remains inside, sealed behind double and triple ranks of Alabama State police. The National Guard, called out by the President Johnson, protects marchers during the five-day walk for freedom from Selma to Montgomery. Viola Liuzzo is murdered by the Klan during this civil action.

- The Voting Rights Act of 1966 is passed by Congress.

- Police beat demonstrators at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago in 1968.

- Stokely Carmichael and Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, Eldridge Cleaver, Bobby Seal, and the Black Panthers, and James Farmer and the Congress of Racial Equality all move towards outright militancy and sometimes armed confrontation as the seams of civil authority in urban America begins to unravel.

- King broadens his message to include economic injustice and continues to march, often citing America’s expanding role in Viet Nam as immoral.

- James Earl Ray ambushes Martin Luther King in Memphis, TN. King is hit in the neck by one high-powered rifle bullet and dies instantly on a second story balcony of the Starlight Motel in Memphis, TN. He and his close associates, including Jesse Jackson, were readying themselves for King’s second march with the Memphis sanitation workers. The first march had ended in violence.

- Shirley Chisholm is elected to Congress and subsequently becomes the first black woman to run for President of the United States.

- Bobby Kennedy becomes the democratic candidate for President, appealing to minority voters across the country. Sirhan Sirhan assassinates him in a California hotel ballroom in June, 1968.

- The Ohio national guard murders students during an anti-war protest at Kent State University.

- The mathematics building at Wisconsin University is bombed by a cell of the Weatherman.

Consider this a short list. What an amazing and confusing decade. Jokes remain about the ‘60s: drugs, LSD trips, dropping out and turning on, the Summer of Love in San Francisco, hippies, VW vans, Wavy Gravy, tie died everything, free love. The idea of America as Whitman had written of in Leaves of Grass, as Jefferson and others had embodied in the original documents, as Lincoln had summarized in the address at Gettysburg, as Mrs. Ames had wanted us to know in seventh grade, this is what I believed America was. The 60s woke me up to the fact that America wasn’t what I thought it was. The lynching I’d fastened upon when I was six now loomed as much more definitive of an America whose reality I didn’t want to acknowledge. But the idea of Whitman’s America was still a good thing to me and I saw my professional efforts as the way to work towards that idea of government of, for and by the people. Only now, “the people” for the first time ever, perhaps, was to include all the people. And America was having a difficult time figuring out how to include all the people.

More of America’s dirty pictures

The reflection back from our national mirror was ugly and too often profane. The transformation of America, the airing of our dirty laundry, the open and very public images were now available to all. They were unable to avoid. These images still cannot be avoided. Though the issues of inequality and social injustice remain very much before us, our problems are no longer hidden from view. Then, the issues were hidden (or denied) except to those who suffered the oppression of underclass citizenship and those who were doing the oppressing. Now that our imperfections are so obviously clear to the entire world, our need is to overcome the insensitivity and outright denial to what is so obviously wrong with Democracy’s frayed fabric.

My part in these cultural events

My part in righting the wrongs as I saw them was small. But to me it was every day incredibly real. And while others were traveling further and putting themselves on the line in Mississippi and Alabama and Georgia in ways that were far more dangerous than mine, I have finally come to respect my own actions during this period of time as also important, as also contributing to the improvement of our nation as a whole and the lives of those I came in contact with. Teaching and social justice work were the same thing then. I believe they are the same thing now. The need is great. The racist forces of ignorance and oppression are strong. The necessity for action is absolute.

All this remains true for me even though I’ve come to understand an important shift in my perspective. In the 60s I was doing my work “for them.” Though it pains me to admit it, I did see myself doing my social justice workto help others. I, and other whites like me, had little understanding that we would be made better by our work back then. Our focus was clearly on making lives better for those with whom we taught and educated. My motivation was a variation on the theme of the white man’s burden. Hurray for us and a pat on the back! The notion that building the relationships necessary to do this work would inspire reciprocity in the learning was yet to unfold for me.

What I understand today that I didn’t understand then is the fact that social justice work frees me. By engaging in the work of social justice, I take control of my own action. The resulting freedom, the reciprocal learnings coming back to me make me more connected to my country and all its peoples. My identity deepens and my sense of power to affect the world I live in grows. My behavior is defined by me and not by my blind adherence to systemic structures of institutionalized racism and economic domination; I define who I am and what I do and who I am becoming. The work of social justice, especially where the vetting of racism is the focus, has to be attended to by those who are of privilege. I don’t think we can ever completely root out the racist assumptions that are thick in this country’s fabric of social and economic intercourse and white superiority. The 3/5s compromise saw to that. We must keep on exposing racism for what it is in all forms, and then act to eradicate its roots and its manifestations. We whites especially need to educate ourselves to see how the institutions of racism of which we are a part, operate. Once we see them, we can refuse them. Seeing through the eyes of others is the issue. But I’m getting a bit ahead of myself here.

The events chronicled in my list defined the national context while I was learning to teach at Madison Junior High School and then later in the City of Syracuse. These events framed my Urban Education. I have come to understand my urban education as the much larger context in which my urban teaching was played out. The process was inductive at the time. My focus was my work with the kids and families I came in contact with within the UTPP. Through it, both in experience and in sensibility, I connected to the place and world beyond. I didn’t travel beyond the borders of the continental United States. But at least I got to the United States. One place I got to there was through the church.

The church as social change agent

Grace Episcopal Church was a hundred yards west of Madison Junior High School. My apartment at the time was the first building just north of Grace, facing University Avenue. 410, to be exact. I’d heard Carl and Moses and Queen and Ruthie talking about the fun they’d had the night before. Goofin’ on each other. The kind of banter that came with them into our homeroom every morning. The kind of chatter they let you hear, chatter that was home talk, uncensored, and full of events of their outside-of-school lives. The boys talked about who’d done what to whom playing pool and the girls talked about how good their singing had sounded, that they’d be sure to win the next singing contest at school. I knew if I started asking a lot of questions, they’d get silent. I wasn’t sure whether to reveal I had ears for this talk as well. But I found out from Doris Gilbert that that church a stones throw away had a program going on for neighborhood kids and that I might want to check it out. She gave me a number to call and a name, Esther Green. I thought that heck, the church was near and if I could help out, I’d get to know my kids in a place outside of school. I knew that taking a bigger step in our relationship could only help my teaching. The kids could get to know me in a different way. I figured that would be a good thing because I knew from experience they knew little about what life was like outside MJHS. I did my laundry once a week at a neighborhood launderette. Early in the fall, some of my students had walked in to use the candy machine and they spotted me transferring my undies from the washer to drier. They were stunned. “Mr. Ratbone! You do laundry here?” I couldn’t figure out if they were more stunned that I had dirty laundry, or that I did my own laundry, or that I did my own laundry there in that neighborhood gathering place? But that revelation clearly had been important to them because I heard from one of the other teachers at school that I’d been spotted by the kids over the weekend. They were going on and on about me and that launderette. So I figured hey, why not show them a few more moves outside of school as well. It all fit. Anything I could do to enhance my credibility with them was fair game at that point.

So I called Esther and we set a time to meet. She said just come in the side door of the church and ask for her. Anyone I’d find would know where she was. So I did.

Grace Episcopal Church was a fascinating microcosm of what happened across the country to white churches who showed sympathy to the black movement. Grace was a small stone edifice, in need of paint and repair here and there, but absolutely beautiful. It’s interior was filled with dark wooden benches and wainscoting. A stunning mostly blue and red stain glass rose window over looked the rear of the sanctuary, and the alter had been brought forward as much as it could to face God’s people. Father Walter Welsh was the priest who directed what happened at Grace. He was tall, slightly grey, a thin man with a thinner pencil moustache with a view of Christ on earth that I’d not found anywhere else.

Grace had been a predominantly white and wealthy enclave on the edge of an encroaching black ghetto when James Farmer and the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) came to Syracuse to test the rental market. CORE would bookend a black couple with white couples as a strategy to see if discrimination was present in the real estate market. Of course, they found rampant and obvious discrimination. When Farmer came to give his first city wide address, no venue would open their doors to him. Not even the black churches further down Madison Street. Welsh invited Farmer to use the Grace sanctuary for his meeting. By the same time next month, white attendance at Grace had dropped precipitously. By the time I met Esther Green, Grace Episcopal was a poor Black church. If memory serves me right, two white communicant families remained active. That’s all. Father Welsh was the first minister I ever knew who lived out a ministry to the poor and dispossessed. I’d thought I’d found a Presbyterian Church in Rochester that did so, but it was all words and money and not direct, one-to-one action. Though the existence of Grace was fragile and vulnerable, Father Welsh taught me what Christian love was really all about. What a difference from the churches of that little town where I’d grown up.

Youth Group

So I started meeting a group of kids once a week, Thursday evening to be exact, in the basement of Grace Episcopal Church. I didn’t have to do much with them. My presence assured their entry to the building. I was basically there to keep an eye on things and that was fine by me. Beyond the occasional homework help I provided, I was the chief learner here. We had lots of fun together in what was usually, a pretty raucous gathering of ten or eleven high-energy young adolescents. The girls sang their Motor City hearts out. I can still sing the words of Mr. Postman just as if they were right next to me. With the guys, I never got to the pool table though I did flash a few wrestling moves. Very few. Mostly escapes!

One Thursday night I’d forgotten to pick up the key from Esther earlier in the day. As the street lights started to wink on, a few early arrivals and I were standing in front of Grace wondering what our next move should be. I really didn’t want to call Father Welch. That man worked long, long days and I knew Thursday evening was one of his few nights at home. I honestly didn’t think much about it when one of the smaller boys said, “Don’t worry Ratbone. I’ll get us in,” and off he took like a flash. The next thing I knew he was up a tree, on the roof, through a window and to the front door. He opened it with a big proud smile for the rest us and in we went.

It was a usual kind of evening. Lots of noise, lots of laughs, lots of banter. Then, one of the girls came and got me. Her face framed worry. Said there was someone at the door making a big racket. I got a little worried myself as I could hear the banging now all the way downstairs. So I went upstairs and without pausing, opened half of the large, heavy, dark oak, arched church door. As I unlocked the door and started to slowly open it, it swung in upon me with surprising increasing force and I was flung back against the wall with the now explosive force of the entry. Four fully armed policemen burst through the portal, weapons drawn, pinning me against the wall. Then the floor. A passing taxi driver had seen my young lad disappear over the rooftop and had notified the police of a robbery in progress. It was the first and only time I’d had serious guns trained on me. A knee dug deep into my back. I was scared out of my mind. After some explaining, the cops gathered all the kids together while I phoned first Esther, and then Father Welch. When the lieutenant in charge found out I knew Willie Gilbert (Doris’ husband) the tension eased and they agreed to let me remain that evening while assuring me that if I ever pulled such a stunt again, I’d end up downtown for the evening. After they left the kids almost burst apart with cop stories. They figured we were pretty lucky that heads hadn’t gotten busted. I thanked them for not provoking a larger confrontation. I was frightened and shaken and could not get the confrontation out of my mind for weeks afterwards. The stories I heard at school the next day brought some ease to the situation. Now, not only did Ratbone do his underwear at the local launderette, Ratbone had finally made friends with the local police.

I don’t know if Father Welch and his work at Grace Episcopal Church went unrecognized in the larger community. He had the support of his Bishop. In fact, Bishop Higley confirmed me on the day I became a member of Grace. The congregation grew back in size although it was slow work. The church became a gathering place for those interested in living out the social justice mission that is Christianity and each Sunday would see a mixed group of worshipers. Father Welch was a luminescent figure in my life. His faith and the challenges it lay before him took a toll on his health but he continued to provide a place of hope for anyone who walked through those beautiful oaken doors as long as I knew him. He also started to build networks across other congregations in Syracuse, congregations who could provide resources for places like Grace and congregations that were in need of resources like Grace. The place I saw this networking work most effectively was after King’s marchers had been beaten at the Edmund Pettis Bridge.

Going to the final day of The March

Father Welsh and other ministers within the coalition decided to charter a flight to Montgomery and join the Selma to Montgomery march for its final day, the day the speeches would be made on the steps of George Wallace’s capitol building, the home town of Rosa Parks, the place where some people said it had all begun, ten years before. Esther called me and encouraged me to go. I was hesitant. But I signed up, paid my money, and packed a small bag. It was my first trip to the deep South.

Why was I hesitant. I’m embarrassed to say, even now, what my feelings were. I knew my parents would object to this direct action on my part. And growing up the way I did, I couldn’t or didn’t have a direct conversation with them about my plans. My Mom would worry. And she’d express that worry. And I didn’t want to add to her worry list, especially since I knew Dad’s alcohol consumption had been worse lately since I’d left college. She didn’t need to be concerned about me as well. But I felt in my heart that she’d want me to do what I thought was right. Dad was another concern altogether. I knew he’d not like it. I think he had little sympathy for the movement. As far as I could surmise, because we never talked about such things, he considered African Americans to be beneath him in circumstance. He was, despite the monkey on his back, a private, dignified individual with his own sense of order about the way the world worked. I think he was troubled by the disorder he saw in life. He thought these people had a place, their place, and that those who believed that place should change were troublemakers. If I went, then I was joining the troublemakers. He would not support my wish or my reasoning. His use of the word “absurd” echoed in my mind as I fantasized about the conversation that never came. So I was hesitant to go because I didn’t want my parents to find out I was doing disobeying their wishes. I was still caught in that authoritarian relationship with my Dad particularly, a relationship sealed in the miasma of alcohol, a relationship I felt I could only change by going ahead and doing what I wanted which I was pretty much doing by the choice of my career. I imagined he would say what I’d heard him say over and over again to my mother through the heating ducts on the interminably long nights in bed, that I “should be ashamed of myself” for doing what I was about to do. So even though it was an amazing trip, I spent lots of time ducking TV cameras just in case my parents tuned in to the evening news to see their youngest son marching with King and his people in Montgomery in 1965. Old Shame was there, even then.

We flew out of Syracuse at 4am in the morning aboard a twin engine Mohawk Airlines DC-3 (maybe?). About forty-five of us headed to the Montgomery Airport with a stop in rainy North Carolina to refuel. First time I’d been in North Carolina as well. We were scheduled to join the March around ten in the morning. Buses would pick us up at the airport and ferry us to the place where we’d rendezvous with the main body of marchers. I wore a white shirt, a necktie, a sports coat, and a London fog raincoat.

Th e rendezvous site was a large athletic field surrounded by a chain link fence of a private Catholic school on the outskirts of Montgomery. Patrolling outside the fence were full armed national guard units. Jeeps and weaponry were readily apparent. The gathering of people was massive, at least to me. It was thrilling to see clusters of marchers from all over the United States holding signs. I was stunned by the number of clergy gathered in that one place. In that one day, my respect for collared prelates leapt exponentially. The March was incredibly well organized. We were told where we would march, how we would march, to follow the orders of the organizers and marshals and that we’d be protected by National Guard soldiers along the way. We were told to march an arms length distance from marchers either side of us until we were given the signal to close ranks. When we got that signal, we were to move together shoulder to shoulder. If trouble was to occur, it would happen as we moved in to the downtown area and the marshals wanted as much space between us and the sidewalk crowds as possible.

e rendezvous site was a large athletic field surrounded by a chain link fence of a private Catholic school on the outskirts of Montgomery. Patrolling outside the fence were full armed national guard units. Jeeps and weaponry were readily apparent. The gathering of people was massive, at least to me. It was thrilling to see clusters of marchers from all over the United States holding signs. I was stunned by the number of clergy gathered in that one place. In that one day, my respect for collared prelates leapt exponentially. The March was incredibly well organized. We were told where we would march, how we would march, to follow the orders of the organizers and marshals and that we’d be protected by National Guard soldiers along the way. We were told to march an arms length distance from marchers either side of us until we were given the signal to close ranks. When we got that signal, we were to move together shoulder to shoulder. If trouble was to occur, it would happen as we moved in to the downtown area and the marshals wanted as much space between us and the sidewalk crowds as possible.

The first hours of this final day of the march was through black neighborhoods. Local residents watched, clapped, waved, posted welcome signs, witnessing this massive turnout of people. When we got to this point the march stretched on for miles. I wondered then what it must have meant to have all these people walking past your home for hours on end. The few people I spoke with expressed thanks that I’d come. It was hard to explain that I hadn’t done much. That they were the people to thank. One woman said none of that made any difference. We were all there and that was what mattered. She was right.

The first hours of this final day of the march was through black neighborhoods. Local residents watched, clapped, waved, posted welcome signs, witnessing this massive turnout of people. When we got to this point the march stretched on for miles. I wondered then what it must have meant to have all these people walking past your home for hours on end. The few people I spoke with expressed thanks that I’d come. It was hard to explain that I hadn’t done much. That they were the people to thank. One woman said none of that made any difference. We were all there and that was what mattered. She was right.

By the time my section of the march reached the capitol, the speeches had begun. Walking slowed after we closed ranks. There were no incidents. Some predictable gestures, some shouting at us, some name calling, some waving of the confederate flag, but no gunshots and no rifles. State troopers sealed off the capitol doors from King and others. All this had been negotiated I’m sure. A podium was set up in front of the lines of troopers and it was from there that the speeches were made. The capitol was very far away from where I was standing and the whole ceremony is now a blur to me. What remains is the feeling of what it was like to stand with such a large, mixed crowd of people from all over this country who gathered on that one day to bare witness to the fact that this country need to bring everyone into the voting process and that the strategies used to deny the vote – poll taxes, constitutional examinations, reading tests, and whatever else – would no longer be tolerated in this country. Some people say they saw George Wallace looking out from a window of the statehouse. I’m not sure it happened. It didn’t have to.

By the time my section of the march reached the capitol, the speeches had begun. Walking slowed after we closed ranks. There were no incidents. Some predictable gestures, some shouting at us, some name calling, some waving of the confederate flag, but no gunshots and no rifles. State troopers sealed off the capitol doors from King and others. All this had been negotiated I’m sure. A podium was set up in front of the lines of troopers and it was from there that the speeches were made. The capitol was very far away from where I was standing and the whole ceremony is now a blur to me. What remains is the feeling of what it was like to stand with such a large, mixed crowd of people from all over this country who gathered on that one day to bare witness to the fact that this country need to bring everyone into the voting process and that the strategies used to deny the vote – poll taxes, constitutional examinations, reading tests, and whatever else – would no longer be tolerated in this country. Some people say they saw George Wallace looking out from a window of the statehouse. I’m not sure it happened. It didn’t have to.

It was difficult finding a bus back to the airport after the rally ended. Somehow I got separated from my group and I had to walk the streets of Montgomery searching for a ride. The shoe was on the other foot. I was so frightened I was sick to my stomach. I didn’t know who was friend, who wasn’t. Me and my white shirt and tie stood out like a sore thumb. Was I tasting a little sample of the what the oppression of living in a terrorist state was like? My imagination was working overtime; I imagined the Klan waiting for me as I rounded every corner looking for my bus. A car pulled up next to me and a Black man and his partner called out, “You need a ride, boy. Goin’ to the airport? Hop in. We’ll take you there.” On their dashboard was a handlettered sign that said “Airport Taxi: Free rides today.” They told me that Black churches throughout Montgomery were providing free rides back to the airport all that afternoon and into the evening. They said they were glad they saw me and what was I doing walking alone like that? I muttered something stupid, I’m sure. I told them they weren’t half as glad as I was that they’d stopped to pick me up. They dropped me at the airport, I gave them $10 for their collection plate, we bid each other good-bye and God Bless and I was ready to be back on my airplane. My stomach was feeling better.

My impressions of the March had more to do with the people I’d met than from the pavement I’d walked. From my journal: “the died-in-the-wool racists as well as the Negroes who have succumbed to the racists will never change. The real hope is in the kids – they shout they are working for “freedom.” I don’t think they will be stopped…it is with this generation that the work must be done.” In 2005, the Southern Poverty Law Center won an academy award for Best Black and White Documentary for their film illuminating the work of that generation of Birmingham youth that led to the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1966. It is a stunning portrayal of the dramatic days that followed the Selma march.

The Rev. Martin Luther King walks by

But the events of this trip were not over yet. The airport was jammed packed with people inside and out. The charter aircraft had to take off in between the normal arrivals and departures so it was slow going. I found a patch of grass near the main tarmac and sat down to rest for the first time since we’d gotten off the bus earlier that day. Again, I was just amazed at the numbers of frocked priests and nuns in the crowd. I guess I’d never imagined the Catholic church as a place of social activism. Despite the encyclicals of Pope John XXIII. I must had dozed off because I remember waking up to a buzz in the people around me. Word was out that Dr. King was leaving and would pass by directly in front of us. Sure enough, within moments, a group of men in open collar white short sleeved shirts surrounding a rather small, hatless individual came walking down the sidewalk, slowly moving through and parting the crowd. They were respectfully given their space. Instead of pressing forward, the crowd moved apart with their approach. It was King. He looked desperately tired. Yet still, as he walked along, he thanked those nearest to him as he moved his way through the crowd. I don’t know whether it was Dr. King, or whether it was one of the small entourage that accompanied him, but some person touched my outstretched hand and squeezed it ever so gently as they passed by. Simple thank-yous were uttered. Then the crowd pressed in on itself once again and the moment was over. Dr. King had passed on by. He passed buy to continue a struggle that was becoming increasingly contentious and divided. We left to return to a Syracuse that remained contentious and divided. A rose colored sky framed the horizon when we touched down once again at Hancock Field and my day of history making in the deep south was over.

I was depressed for days after Rev. King was murdered. Even now, my eyes brim as I tap out these words. This work remains incredibly important, and incredibly complex, and incredibly difficult. If I learned one thing from this trip, it was this. Every act counts. Every witness. Every step. Then and now. Every voice raised. It was needed then to urge a recalcitrant, frightened Congress forward. It’s needed now to do the same.

My urban education was personalized in many more ways. Washing Steve’s light green Volkswagen after it had carried him back from his work in the Mississippi Freedom schools complete with bullet holes; Suzanne’s lecture on writing curriculum for the Freedom schools, curriculum that included the likes of Sojourner Truth, Frederick Douglas, Rosa Parks, Ida B. Wells and Mary Mcleod Bethune; my own refusal to attend a rally in Syracuse where members of SDS were going to chain themselves to bulldozers scheduled to carry out another act of urban renewal; Robert Kennedy’s visit to and stroll through MJHS; listening to Daniel Berrigan organize resistance to the war effort; becoming one of the kids in the balance of powers role playing task as I started to work as a staff assistant in the UTPP; telling my father I’d been south and hearing him say, “Oh No. That was not a good thing to do,” getting dizzy in disbelief and crying with my wife the moments after I’d heard Robert Kennedy had been shot; living through a 2am fight with my good friend, a Marine, that nearly came to blows over our involvement in Viet Nam; and listening to Mario Fantini’s farewell speech after control of the Madison Area Project had been transferred to City Hall.

The responsibility that is Teaching

No series of events since has affected me in the way these events did. At the time, I was unaware of their cumulative effect. I was aware that for the first time, secrets long endured by disenfranchised Americans in the South could no longer be avoided. As we learned later during the pranksters’ break-in at the Pentagon, television ended our excuse of innocence. No longer could we avoid the injustice that rented our social fabric. In retrospect, the social convulsions of the 60s, the see-saw of justice and injustice played out between a government and its people, the right to march protected by law through country that days earlier was prepared to lynch, torture, and murder citizens whose sole crime was to speak truth and demand what was rightfully theirs, were the inevitable results of a country refining its core purpose and mission. The race question that Gunnar Myrdal had put before our parents’ generation, was coming home to roost.

To this day, it is hard to separate my learning about teaching from the times in which I learned to teach. In this urban education program, teaching was an act of social justice. The very fabric of the program was to make a difference in how schools operated for those most in need. Memories are useless if they serves no purpose. Mine have fed both spiritual and political ends. The memories of these urban days continue to fire my passion for teaching and keep me focused to connect. As we all know, King was so right. Injustice anywhere is injustice everywhere! Injustice occurs when invisibility becomes systemic. Today, I expect my students to make a difference for the children that are most invisible in their classrooms. I want them to know the effects their own race, power and privilege have on those whose race renders them powerless. I expect them to know all sides of their teaching role. Back then, I believed schooling alone was the answer. Now, I know it’s only one of the answers. Nevertheless, teachers still need to see themselves as agents of social change. The racial education of whites is central to the task. Teachers need to know how to swim against the currents that serve to keep our society from moving ahead. They need to turn over the rocks that define our curriculum and teaching practices and root out racist assumptions and practices. The democratic vision is what we have to guide us. It remains before us and it remains so much more than a myth. It is, mythic. It is perhaps, the only thing we have left to keep our eyes on the prize of all people sharing equally the benefits of citizenship in this democratic nation – of, by, and for the people. All the people.