This week, we will return to our reading of Nigel Clark’s book “Inhuman Nature”. In particular, we will focus our attention on chapters 6, 7, and 8.

In Chapter 6, “Hurricane Katrina and the Origins of Community”, Clark focuses on the impacts of the August 2005 landfall of Hurricane Katrina on New Orleans. Although the storm was devastating from a variety of perspectives (loss of live, loss of property, feeling of vulnerability, and loss of New Orleans history, to name a few), Clark argues that one of the most thought-provoking effects was the alteration of the sense of community. He points out that the fragility of human life, especially in the face of natural disasters, is the reason why we seek community to begin with. Clark writes: “I want to explore the proposition that natural extremes or ‘disasters’ are not simply visited upon pre-constituted communities, but are themselves imperatives for the very process of communal or social formation” (p. 139).

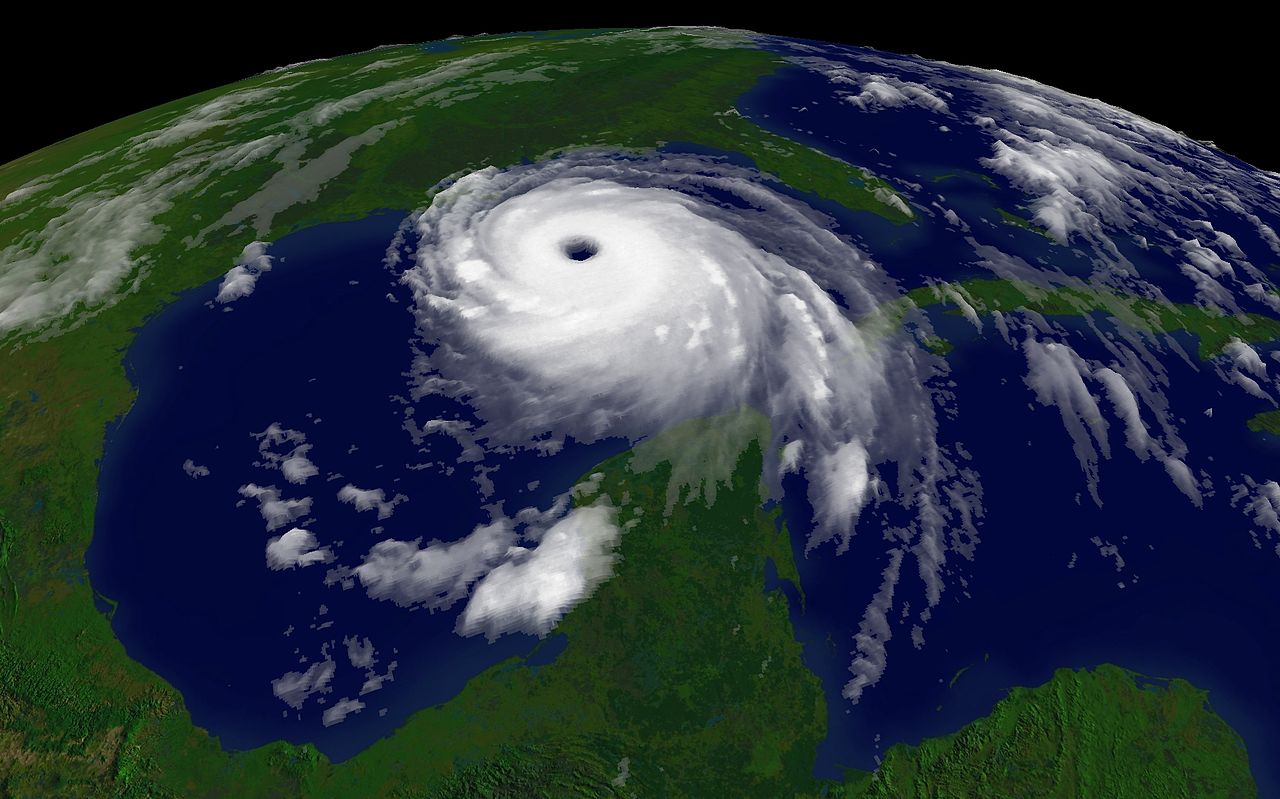

Graphical visualization of Hurricane Katrina on August 28, 2005 (courtesy of Wikipedia)

Clark’s idea is intriguing. If humans never felt threatened, would they have ever sought out a communal social structure? Likely, the answer is no. Among other reasons, communities exist to protect their members from external threats and to provide comfort and support in times of hardship. As Clark points out, it is often these times of hardship that bring out the best in people. We all heard stories from New Orleans about people rescuing their neighbors from floodwaters and of citizens in safer areas of the city opening the doors of their homes to other citizens that had been displaced. On the one-year anniversary of the Boston Marathon bombing, I am reminded of stories about runners who had just covered 26 miles continuing to run straight to the hospital to give blood. Times of hardship inspire people to help one another, and these times of hardship are the building blocks of community.

Natural disasters, especially, can represent a blank canvas for the formation of communities. Clark quotes Michel Serres, who suggests: “Floods take the world back to disorder, to primal chaos, to time zero, right back to nature in the sense of things about to be born, in a nascent state” (p.145). So, although Hurricane Katrina will leave behind a legacy of pain to hundreds of thousands of residents, it also represents a new beginning and an opportunity for the best characteristics of human society to shine through. Among many other stories, it led to the formation of groups like the “Cajun Navy”, a rapidly-assembled group of hunters and fishermen who used their boats to rescue over 4,000 people from their flooded homes (p. 147).

Of course, there are negative stories as well: those of government bureaucracy impeding rescue efforts, racial and socioeconomic equality, looting, etc. Unfortunately, natural disasters do not bring out the best in everyone and, ironically, sometimes it seems as though the people who have the least are also those who give the most. Clark explores the idea that these failings to act originate from our ability to turn away from the things that are difficult, subconsciously recasting our perceptions to make ourselves see the problem in a different light.

The obvious related question to Clark’s discussion of Hurricane Katrina is how the city of New Orleans should proceed into the future. We live in a volatile world, and the city’s position will become increasingly perilous in the face of modern climate change. Should flood-prone areas be rebuilt? Should people be living in an area that is virtually destined to be destroyed again? My guess is that Clark would say no. As he argues throughout the chapter, a natural disaster gives people the chance to start anew. Rebuilding in a threatened area doesn’t seem like a fresh start; instead, it seems like trying to navigate backward to a place that existed in the past. If we believe Clark that Katrina represents an opportunity, maybe we should consider that New Orleans was given the opportunity to seek a safer, more secure future by rethinking the city’s rebuilding.