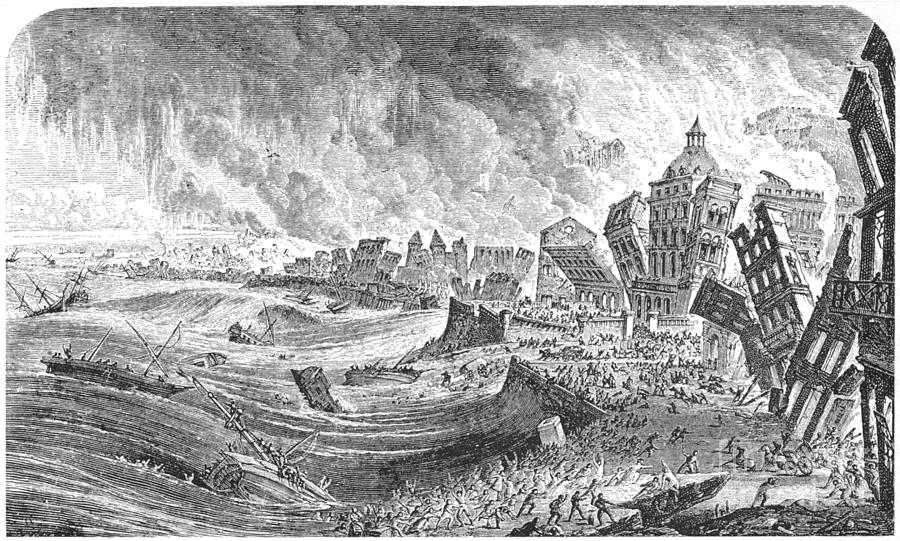

We continue in week nine to study the Anthropocene using Nigel Clark’s book Inhuman Nature as a way of conceptualizing an earth system without a human presence, or a nature that transcends human needs so as to render them irrelevant and subject to earth’s mercurial processes. In Chapter 3, Clark draws on the French philosopher Emmanuel Levinas to critique the argument that the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami was destructive primarily due to political and economic structures, and in Chapter 4, Clark takes us back to the 1755 Lisbon Earthquake that left Europe in a wrecked state physically and emotionally, showing how this material process impacted a young Kant more than one would think in studying the critical philosophy that he helped to instigate.

Clark hopes that Levinas can “help us come to terms with the human experiential dimension of physical forces far beyond our measure” (57). In contrast to Husserl, who postulated a solid, steady ground on which we experience life and can rely on, Levinas offers a “ground which can unground,” that is, an Earth that for all of the elemental enjoyments we ascertain – Sun, tranquility, the pastoral – is also an Earth that can radically alter our being, existent completely apart from the way of life we believe it should conform to. Yet in 2004, after subverted plates in the Indian ocean caused a massive earthquake and tsunami that killed over 230,000 people, Clark finds that his “fellow critical thinkers” placed the tsunami into “a familiar storyline, into an ‘economy’ of causes and effects that preceded the event itself” (58). These causes and effects, however, were not considered to be Earth’s geologic processes, but instead, social inequalities and economic structures were largely blamed for the extent of the damage.

Indeed, the first time I learned about the tsunami was in a sociology course that looked at Naomi Klein’s Shock Doctrine, an expose on how Western governments, multinational corporations, and corrupt NGOs have exploited situations such as in Sri Lanka to capitalize on the aid that comes in from abroad and to rebuild fallen villages and infrastructures that act to perpetuate and worsen human inequities. While Clark acknowledges that this viewpoint is vitally important, and that some destruction could have been mitigated had human life been structured differently, he also points to the elephant in the room that is overlooked: that the root cause is an earthly one beyond our control. Although social justice must be part of the conversation, there will be catastrophes, disasters, and natural events that “we will be called upon to respond” but “for which we are not responsible” (66).

In recognizing that the consequences of Earth’s processes are not always our fault, Clark turns to Levinas to explore the vulnerability at stake, not only directly to the catastrophe itself, but even from miles away, through our human urge to empathize with the victims of the tsunami. This opening up, or ‘risky uncovering of oneself’ challenges the idea of an ‘autonomous, self-directed subject’ while presenting an opportunity for a positive response and re-construction – we have heard harrowing stories of tourists and locals alike rescuing each other (Clark almost goes so far as to call the tsunami a ‘gift’ if it is seen as a moment for spontaneous collaboration). Ethics vis-a-vis inhuman nature, then, entails working across differences that cannot ever be fully accommodated, since Earth has a supremely different agenda than our day-to-day routines.

In Chapter 4, Clark goes back even further in time to show us that a ‘social turn’ in the face of a natural disaster is perhaps a rational and understandable thing to do. Most know Immanuel Kant for his late work that set the tone for critical philosophy that remains until this day, but until reading Clark I had not realized that Kant had earlier written a work entitled “History and Physiography of the Most Remarkable Cases of the Earthquake which Towards the End of the Year 1755 Shook a Great Part of the Earth” (87). As Clark shows, this is remarkable because it is Kant that is largely attributed for a more idealist philosophy that outlines human capacity for transcendence as our fundamental reality, rather than a materialism that places more agency on nature itself.

Given all of the various explanations for “why” the earthquake occurred ranging from the teleologic to the pessimistic, Kant stakes his ground on the belief that human beings are alone in defending themselves “amidst the best and worst that nature has to offer, and it is up to us to try and comprehend these variable forces, to accommodate ourselves to them, and to show consideration when they lay others low” (89). Essentially, the early Kant is saying that because we are bound to this planet, and thus infinitely vulnerable to its processes, we must use every facility we possess to prevent our untimely destruction from happening once again.

However, as Clark points out in following the philosophers Susan Neiman and Quentin Meillassoux, “If the worldly actions we conceive of, following our own imperatives, are to have the outcomes we anticipate, then it is necessary that the material world we are acting upon complies with our instrumental intent as well as our knowledge of it. In order for us to assert ourselves, confidently and effectively, we have to believe that nature is pre-disposed to our plans: that ‘(t)he world was made for our purposes, and we for the worlds’” (91). While initially Kant’s thinking was a response to our vulnerability to nature, it now becomes the impetus for our actively taking part in the mediation and mitigation for natural disaster, and thus also something more comfortable for our psyches: rather than relinquish our agency to that over which we cannot control, we can position ourselves, through science, rationality, and collaboration, to overcome these disasters, and when they hit, be ready for them.

What Clark calls ‘radical asymmetry’ refers to this relationship, both in the misguided notion that we have dominion over nature and what he believes is actually the case, which is that our human achievements can be laid bare by vast geophysical processes. But Clark does not wish us to lose hope in the face of this realization; drawing on the philosophy of Alphonso Lingis, Clark argues that what we know and can know should be celebrated, for they “are our point of contact, our opening to the cosmos, our invitation into worldly existence” (102). That which we don’t know about, but that exists nonetheless, exists in a “field in which things witness one another… So it is not just a matter of elements and entities which exhibit themselves to us, even as they harbor their own inner secrets, it is also a matter of things flickering between attraction and repulsion, disclosure and withdrawal, amongst each other – with or without our permission or our participation” (105). This is what Meillassoux means by ‘after finitude’, or beyond what we can know, and is a key philosophical turn for Clark.

While Kant laid groundwork for knowing as much as we can about what we can observe, measure, probe, and talk about in the world, Clark hopes to renew this original critical spirit by examining ways in which we can conceptualize, frame, or imagine the beyond-human, and the inhuman nature of the Earth ‘in itself’.

Great overview. Thanks Emil.

Thanks for the great overview, Emil! I just want to add by sharing my own impressions from the reading. The most striking idea from these two chapters, in my opinion, is that earthquakes are profoundly different from other tragedies in terms of how they impact the human psyche.

Of course, there are many events that humans may consider tragic: a sudden illness, the loss of a loved one, an accident, extreme weather events, terrorism, and many others. For obvious reasons, these events and their aftermath can be traumatic to those involved, evoking emotions ranging from sadness to anger to confusion. They can cause humans to lose faith in each other, to feel vulnerable, and to doubt their futures.

However, as Clark continually comes back to, Earthquakes are fundamentally different since they cause people to lose faith in the one thing that seems most fundamental and constant: Earth’s surface. Humans are usually surprisingly resilient in the face of tragedy; this is probably at least in part due to being able to take comfort in known familiar things. Earthquakes, though, shatter this perception of fundamental stability. When Earth’s surface ruptures and moves, it completely disorients us from everything we know, yielding deeper confusion and disorientation than other traumatic events. When we can no longer count on the stability of the ground on which all of our existence rests, there is little left to anchor us to reality.

For these reasons, earthquakes can have profound impacts on how we perceive ourselves, our society, and our existence.

Pingback: Roy Bhaskar, Critical Realism, and Interdisciplinarity and Climate Change | ETC Evolution·