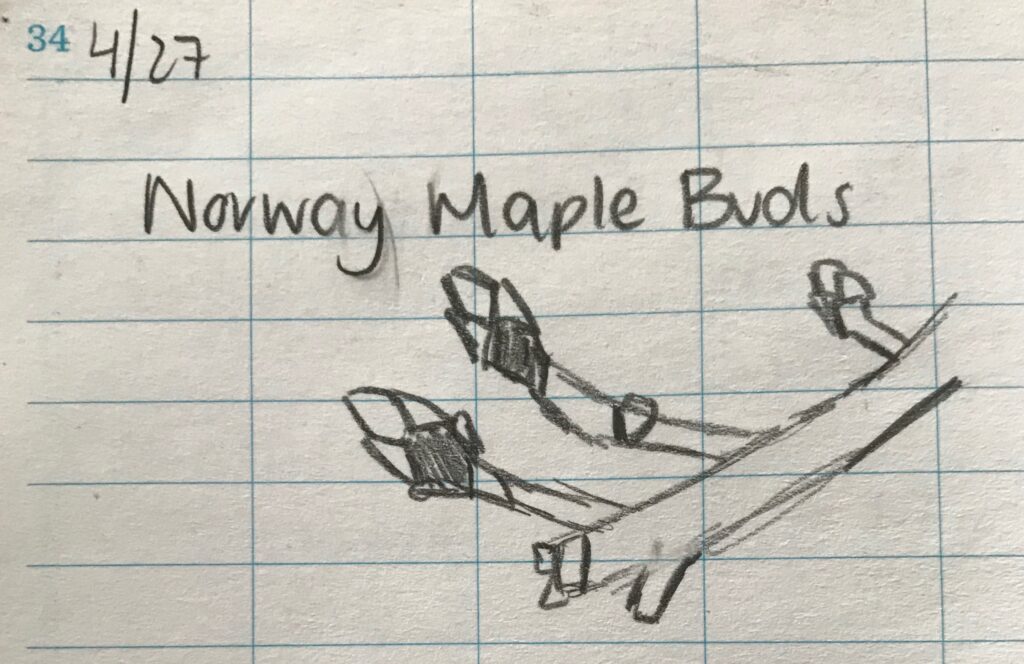

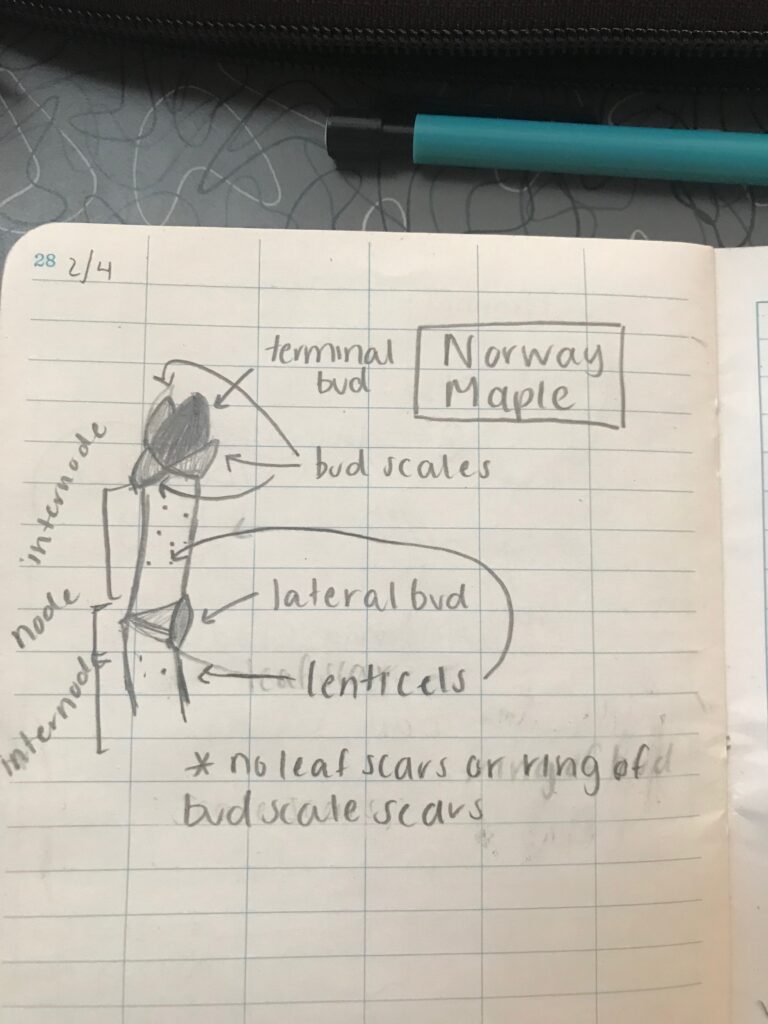

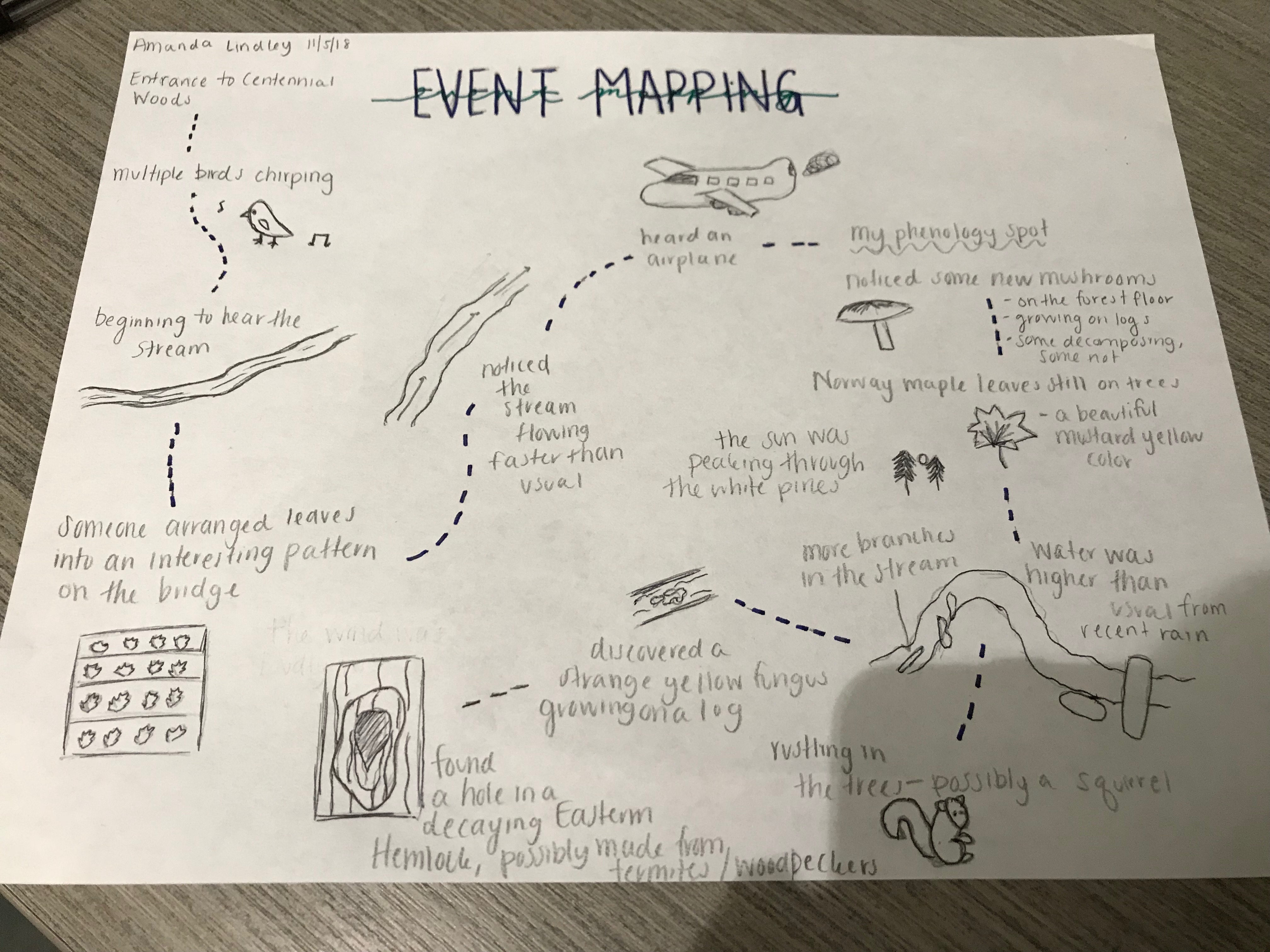

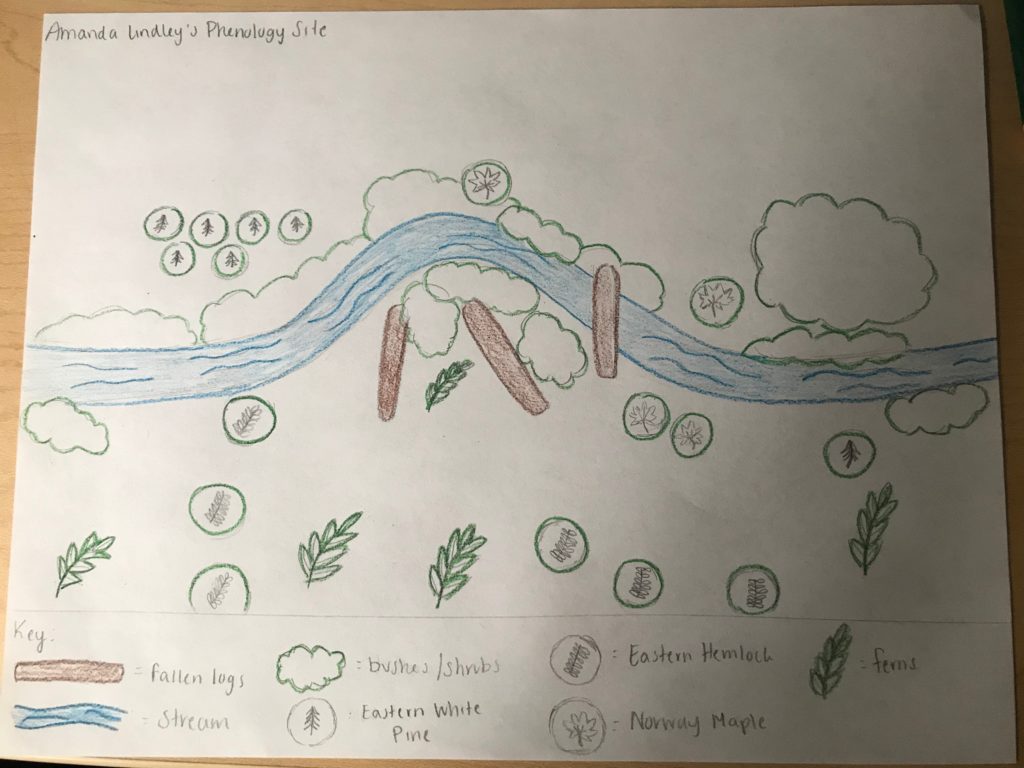

I was excited to visit my phenology spot one last time before the end of the semester on a beautiful spring day. Since the time I visited the week before, very little had changed in my spot. I noticed that some of the norway maple buds were getting bigger, and I found some fiddleheads by the stream bank that I had missed earlier.

I spent some time relaxing in my spot, listening to a few chick-a-dees chatting in the treetops above me. Dipping my fingers into the cold stream, I realized that I truly became connected to this spot over the course of the year. I’m not sure I became a part of my spot, but it certainly became a part of me. We had both grown and changed throughout the year, and I feel as though this little area in Centennial became a significant part of my freshman year story. Even if I never visit this spot again, it will carry on just as it did before I knew of its existence. But I changed a bit since learning about my spot. I regained a childhood love for the environment that I had outgrown a bit since growing up. I’m thankful that I got a chance to fall in love with nature again.

Nature and culture are certainly intertwined in Centennial Woods. Member of the Burlington community come to walk their dogs and escape into a calm outdoor setting. I’ve passed UVM students picnicking on sunny days and exploring the streams. As a recreational outdoor experience, Centennial Woods plays a key cultural role in the Burlington and UVM community as an escape from the stresses of modern life.